On February 12, 2013 I had the pleasure to discuss using Vagrant, Chef Solo, and Git to create development environments that could be quickly stood up and easily discarded and replaced. My presentation focused heavily on stories about computing and workflow, while demonstrations ran in the background.

My slides ran on Reveal.js and are available here. Because I write my presentations long-hand before I give them, I can post something very close to a transcript of it below.

Update 2013-05-08: Tonight I'm presenting this same talk for the Fox Cities PHP Users' Group. I chose to update this post with the latest version of my slides and presentation. It feels a bit revisionist, but I did it anyway.

/static/

Hi. I'm version2beta. That's version, the number two, beta. I'm version2beta on twitter, github, linkedin, skype, etc. I'm at version2beta.com online.

In meat space, some people call me Rob. There are also some short people who call me Dad.

Since we're talking about Vagrant, I decided to dress like a vagrant. I even have a hole in my armpit. Since the last time I gave this presentation, I've developed a hole in my other armpit too.

We're talking about Chef tonight, so I'm going to run this like a cooking show. We'll start by putting the casserole in the oven.

That's how it works, right? The TV chef makes up the entire dish in advance and tosses it in the oven just before the cameras start rolling. Then, live in front of a studio audience - that's you - they make the dish from scratch. And they put it in the oven. And then they pull the other one, the one they've had cooking all along, out of the other oven.

That's what we're going to do. Preparing this dish live right in front of you sounds a little scary, so instead, we'll just toss this one in the oven and let it bake, while we just talk some about the ingredients.

I think this is actually going to work out pretty well, because I actually made a whole bunch of these casseroles in advance and stuck them up at Github. All you have to do is grab one and throw it in the microwave for about six minutes. The first step is to grab a frozen casserole from Github. There's the link if you want to follow along real-time, we're going to go slow enough. But no worries, it'll be up again.

Actually the zeroeth step is to install VirtualBox and Vagrant if you haven't already. That's the other link, Vagrant Up Dot Com. We don't cover installing these two programs because it's easy and they cover it just fine on the website. If you want to install them right now, that's fine. You'll have plenty of time. I haven't even told you about my grandfather yet.

But first, I'm going to git clone this repository -

[Shell: git clone git@github.com:Version2beta/vagrant-chef-wordpress.git]

and then change directories into the repository -

[Shell: cd vagrant-chef-wordpress]

and then run vagrant up. I love that. Vagrant Up. I always wanna say Vagrant up, muthafucka, Vagrant up. I don't know why. Or when I'm in a family friendly venue, I just say Vagrant up, yo.

[Shell: vagrant up]

That'll be done cooking in about 6 minutes. We'll come back to it.

Okay, I'm Version2beta. I know a lot of people start off their presentations with the "Why should you listen to me anyway?" slide. "I'm blah blah blah and I blah blah blah so you can blah blah blah."

I haven't written any books, or keynoted any conferences. I have a few cool open source repositories and a small Twitter following. So instead of bragging about the little things, I decided to tell you about my grandfather instead. And my mom, too.

So grandpa always said he was a total screwup, but what he really meant was he was a geek. He almost got expelled from high school for his senior prank. He made explosive BB's and tossed them on stage during the finale of the senior talent show.

A fews years after he graduated from high school, he and his brother Bill both signed up for the Navy. It was world war two, they both had new spouses, and Grandpa even had a baby girl at home.

Grandpa was stationed in Rhode Island testing missiles. I don't know what Bill did in the Navy, but I do know that when they'd done their two years of service, they got four years of college paid for on the GI bill, and they squeezed every penny they could get out of it.

In four years at the University of Pennsylvania, Grandpa did a bachelors in engineering, a masters in business administration, and a masters in the brand new field of operations research.

In fact the university had created that Operations Research department specifically at the request of the federal government. I heard it was the Office of Strategic Services that asked for it.

At the end of his four years at University, in 1949, Grandpa went to work for RCA. He started out as an engineer for their military contracts. When he retired from RCA in 1989, he was RCA's chief technical liaison to the Pentagon.

Hey this is cool. I recently discovered that Grandpa wrote a book in 1951 called "Music in Industrial Plants." Like a boss.

In comparison, my Uncle Bill was a slacker. In four years of college all he managed was a bachelors and a masters in chemical engineering. But look at this. At the beginning of college Grandpa and Grandma had only one child, my mother. At the end of the four years, they still only had one child. When Grandpa and Bill started at the university, Bill and June didn't have any kids. Four years later they had four kids. So Bill was maybe more productive during his college years than my grandfather was.

Uncle Bill went on to become a senior engineer on the team that invented PVC. And later he died of cancer. I could be wrong, but I've always suspected a connection.

The story about my grandfather doesn't really have anything to do with our topic for tonight, I just like telling it. But I do have a story that can tie it together. On Valentines Day in 1946, the Moore School of Electrical Engineering at the University of Pennsylvania announced they had built the first general purpose electronic computer. You've probably heard of it. It was called Eniac. Eniac was Turing complete, back in the days when Alan Turing himself was still Turing complete. Eniac was capable of solving a wide variety of problems, all of which had to do with the firing of artillery.

Around this same time, Grandpa had a habit of hanging around the Moore School, and my mother had a habit of hanging around him.

I know when I was a kid, I had a lot more freedom than kids have today. When I was in elementary school, I ran the streets ’til dusk, rode my bike wherever I wanted, hung out with friends, and only sometimes got in trouble for it.

My mother apparently had a little more freedom. When she was in elementary school, she was allowed to hang around with college boys and play tic tac toe against the world's first electronic computer. In fact my mom beat the computer at tic tac toe. At least, that's her story. She also says that Grandpa accused her of lying and said no one could beat the computer at tic tac toe. When I asked him about it, Grandpa denied ever doubting her.

I spent the 90's doing industrial controls, some ladder logic, some programmable logic controllers, and then the best part, human machine interfaces. Except they were still called man machine interfaces back then.

I had a photography hobby though. My specialty was tastefully photographing attractive women without their clothing, and sometimes I photographed flowers. I even won a few awards and was invited to lecture at a local university.

The Internet was getting pretty interesting so I decided I should have a website for my photography. So I did the only logical thing. I built myself a web server.

Don't tell anyone but back then, I was running IIS on Windows NT 4.0 Server.

For like the first six months. I hosted my own Windows web server in my office at home, connected to the internets with two 56K modems. Shotgun.

This was my first internet dev environment. It was also my first internet production environment. I broke it a lot. Soon, I replaced IIS with Apache, and Windows with Red Hat and then NetBSD and then FreeBSD.

These were exciting times. I got a lot of experience.

These were the days when just being there on the ’net would get you visitors. Having one modest web site was enough to keep the average hobbyist busy. Plus my website had naked people on it.

Let's zoom forward a few more years. By 2001, most of my work was on the Internet. In fact, I was doing development and systems administration full time for a company I owned part of. We hosted a few hundred websites, had email for a couple thousand accounts, and provided Internet access for about a thousand families.

Yes, we were a dial-up internet service provider. And no, we didn't last very much longer.

I had an interesting experience last weekend. I was teaching a Ruby class, and one of the participants works for a company that bought a company that bought the company that I owned part of. So this kid was telling me that he's now responsible for maintain code I wrote more than ten years ago.

And he didn't even try to hurt me.

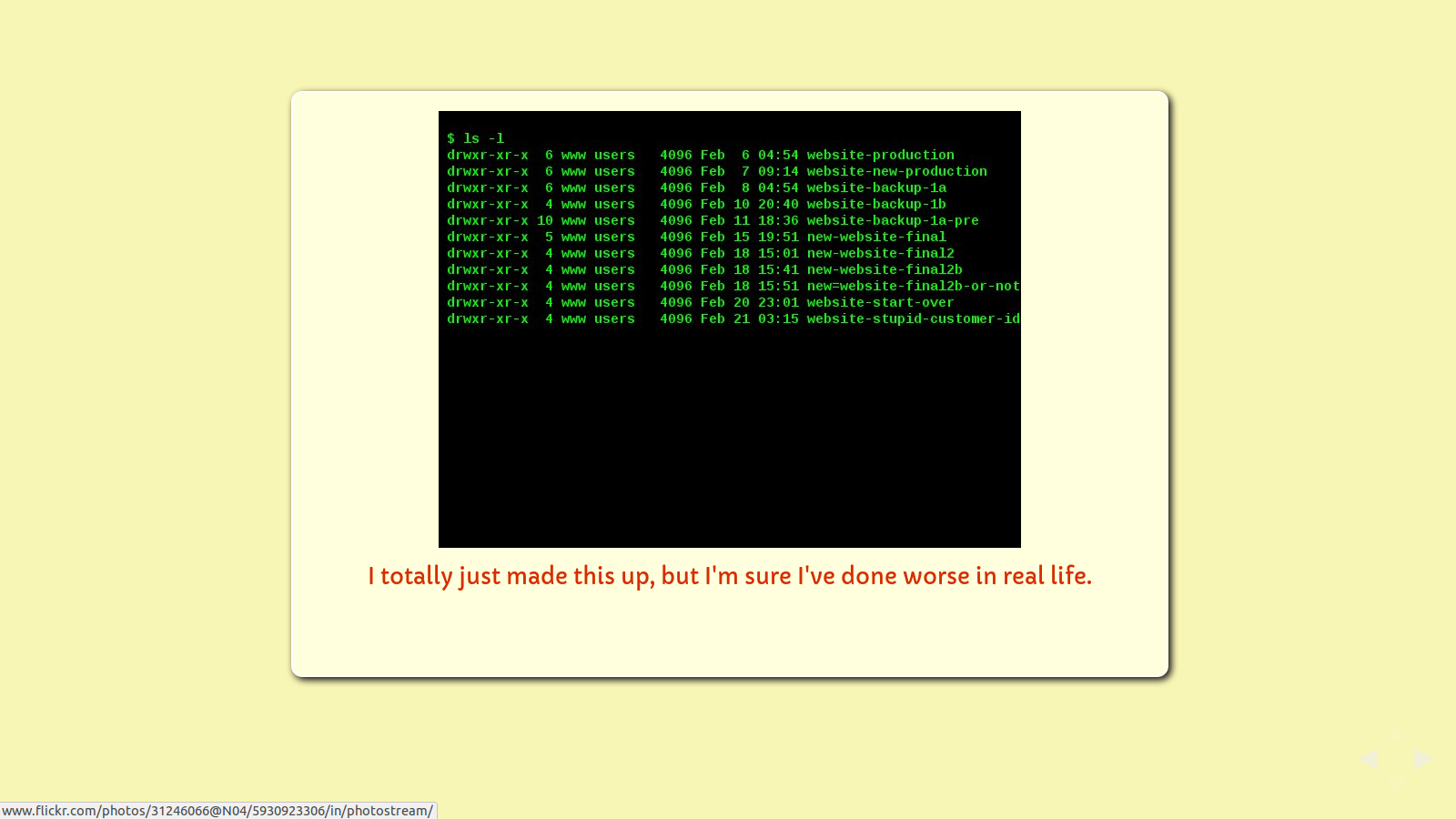

I don't have any screen captures of those days to share with you, so I made one up.

You've seen file structures like this, right? Where there are four versions of "Final"? Backups upon backups? No good way of knowing what's actually what?

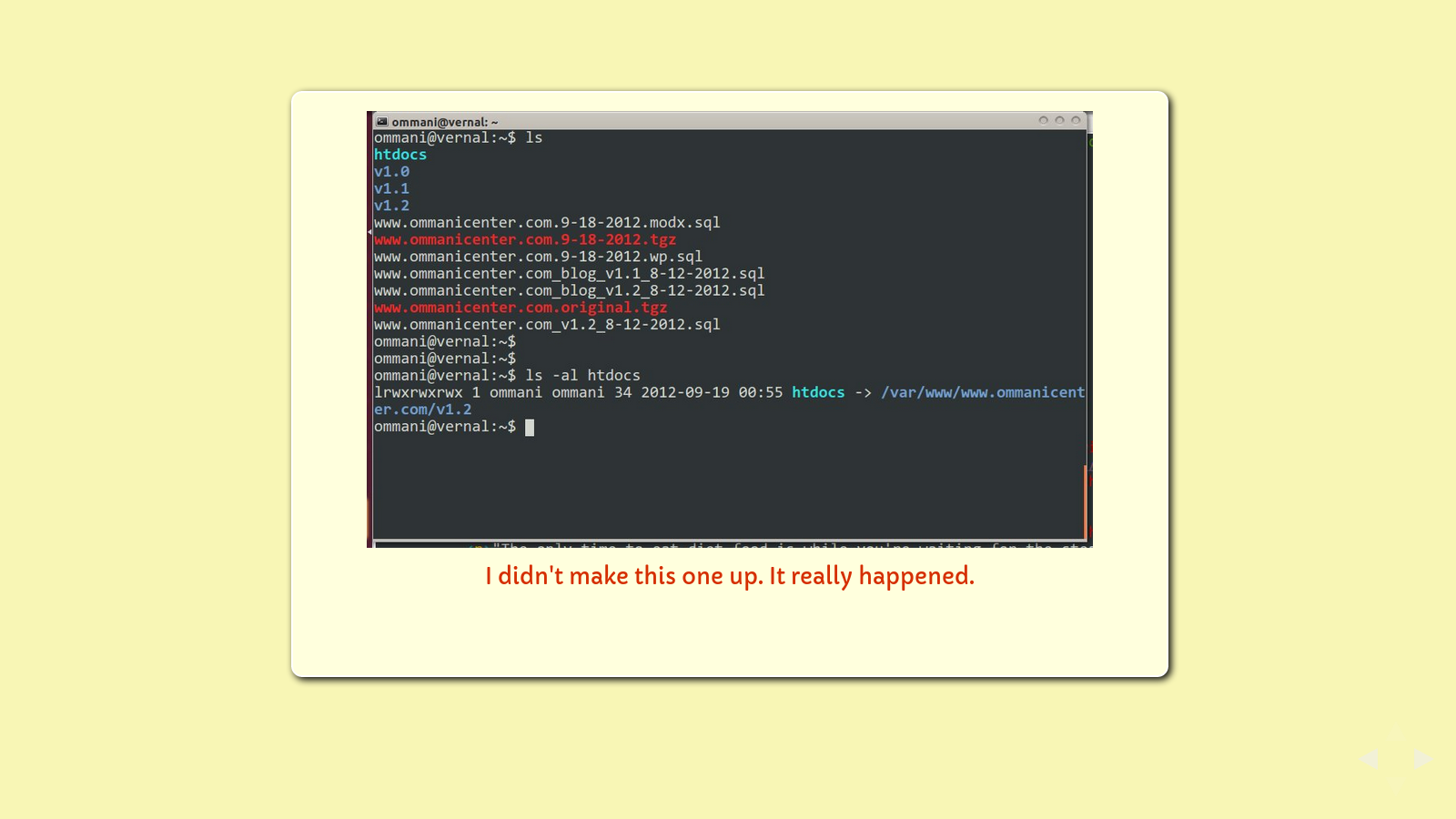

Okay, lets jump a few more years. Now the dev environments are getting organized, although still not on version control, since that's actually still kinda hard to do with a CMS and relational database.

By the way, has anyone here solved that problem? Who's running Wordpress, or Drupal, or Joomla or a similar CMS?

Keep your hands up if you're also using Git?

Okay now keep your hands up if you're also versioning your database?

For about five years most of my web work was done in an application framework and content management system called MODX. It's pretty cool, works okay.

Here is a site that is running on MODX now. Over the past four years, it has gone through three different major rewrites. The first one I saw was static. I didn't build it, that's what I inherited. That's version 1.0.

Version 1.1 is on MODX and Wordpress, but it's really just the static site cleaned up and put into a content management system.

Version 1.2 is an incremental improvement from there. Still MODX and Wordpress.

The thing I want to show you here is that version 1.1 was the dev site, up until it launched and then it became the production site.

The way I built this system, launching was really easy. I just point htdocs at the correct version with a symbolic link.

After version 1.1 became the production site, version 1.2 got started up as the new development site. Obviously if we continued along this path, version 1.3 would be the next development site.

This setup works. It's good for small sites on shared servers where you don't have to worry about breaking too much shit.

Oh, and when you're the only developer on the project.

And you don't need very many versions, or branches, on the code.

And you always have internet access.

And when you don't have to worry about dependency hell. You know, when one version of the site needs one version of a package, but the development version needs a newer version. That's why god made virtualenv. And rvm. And rbenv. And chruby. And so on.

This way of doing it also works really well when you want your development site to use the production site's database. Which of course you never do. Especially not by accident. There are some stories there.

So yeah, this was the state of the art for me a couple of years ago. It's not like git and mercurial and svn and everything else weren't available, I just wasn't using them.

I work now for a company called Tartan Solutions and they make a platform for running programs that do profit and cost management stuff for big companies. For instance, one of the programs will calculate how much every product in a product line will cost for the next year given current sales forecasts. Even if you took these three little parts that are used in a bunch of different products and combined them into two parts and got them from a different provider, say in China.

When I was interviewing for my job, I hit on a real winner for selling myself. I said, "My problems are not big enough."

My problems are not big enough.

Sure, I can make my current problems bigger. That's easy. You've probably seen this.

Let's say you a problem you need to solve with an internet application. So you install Drupal. Now your problem is twice as large.

I'm trying to go the other way, though. I've adopted this new philosophy. It's my Twitter bio right now.

It says, "I think I'm free for lunch."

No, wait. That was the old one. The new one is "When you only have two ducks, they are always in a row."

So that's my strategy now. I eschew complexity.

It's actually really cool. It means I can do things like make a completely separate development environment for every project, and they build themselves automatically.

It means I can make a separate server for every production site. Unless of course I can manage to host it without a server at all.

I'm also avoiding complex, monolithic application frameworks and content management systems. I'm focusing on microframeworks and services that collaborate.

This all fits together with our dev environment, right? It's done cooking.

[Browser: http://localhost:8000/wp-admin/install.php]

So here's a brand new Wordpress installation ready to happen.

[Browser: Fill it in.]

That was git clone and vagrant up. Two commands. If you want to work directly on your new server, it's just vagrant ssh.

[Shell: vagrant ssh to development environment. ls -al blog]

Pretty slick. Let's look at it more closely.

Discuss:

Vagrant and Chef are Ruby. Ruby is optimized for programmer happiness. Really, when Yukihiro Matsumoto created it, he made programmer happiness a primary goal. Here's one think I've learned from observing the Ruby community: You know you're a Ruby programmer when you stop buying cheap booze for medicinal purposes and start buying expensive whiskeys instead.

Chef is a DSL, a domain specific language, which is a way of saying we can make our own commands in the language of our problem domain. In this case, managing servers.

Does anyone here read TheChangelog, or listen to the podcast? Vagrant was created mostly by Mitchell Hashimoto, and yesterday they recorded a podcast with him as the guest. It was his second appearance on the show. I got to listen to it live, and I asked Mitchell several questions, including whether there was anything he wanted me to tell you tonight. There wasn't.

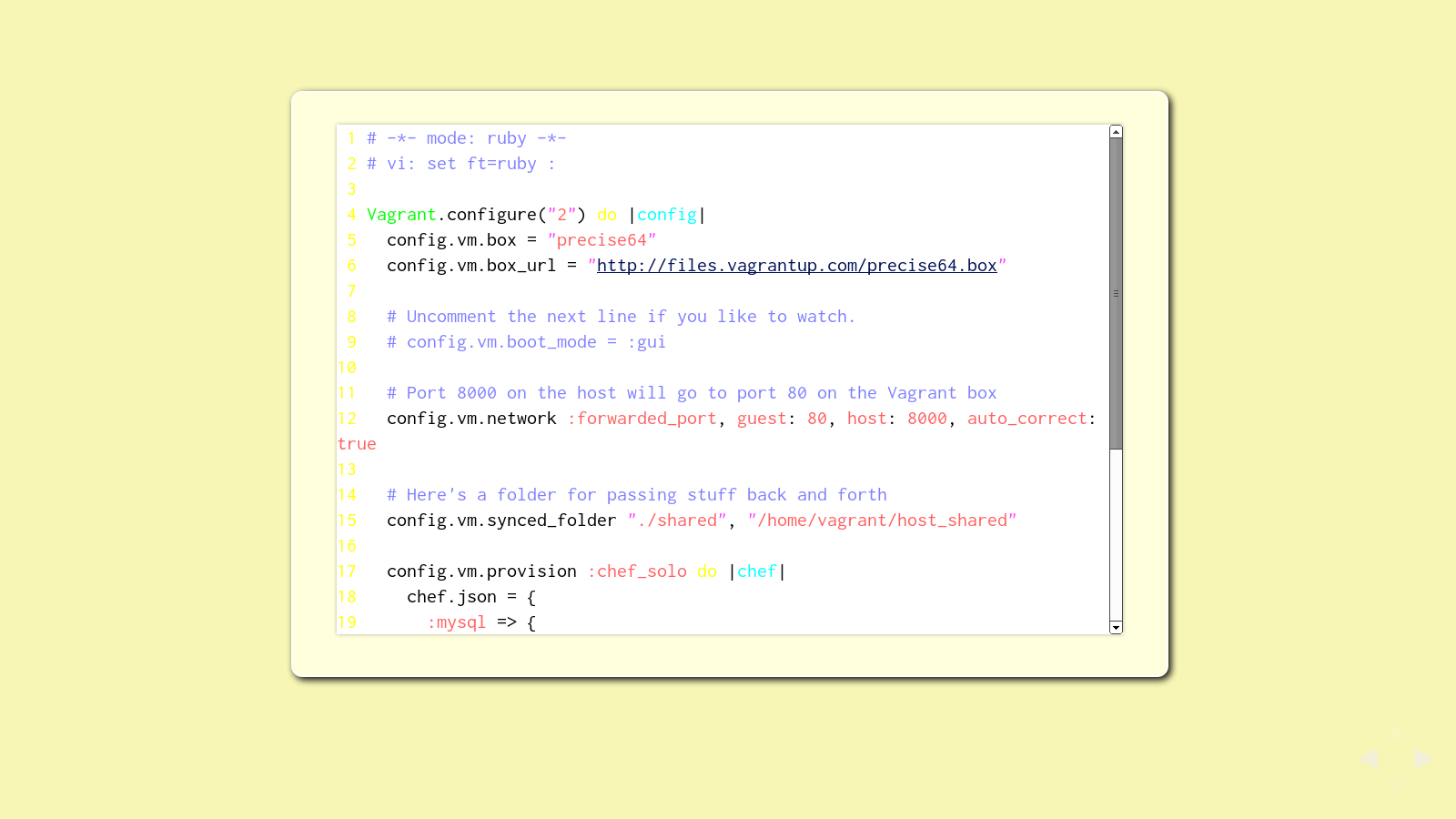

Vagrant recently came out with version 2. Not really, but that's what the part that says "configure('2')" means. It is version 2 of the configuration, even if Mitchell is building up to Vagrant version 2 slowly, starting with versions 1.1 and 1.2.

This Vagrantfile specifies Ubuntu 12.04 from vagrantup.com. Vagrantup.com doesn't offer very many choices for boxes, but there are other sources too, and it's easy to make your own.

We're forwarding port 8000 to port 80 on the Vagrant guest. This is happening on all addresses for the host computer, so you can access the guest's web server from any host on the local network.

We share a folder between the host and the guest operating system. This makes it convenient for passing files in.

Outside of config.vm.provision is all VirtualBox magicness.

Inside of config.vm.provision is the Chef magicness.

This is Chef Solo. We don't have a Chef server. We're not using hosted Chef. We don't have a persistent store of each Vagrant boxes' configuration. This is kindergarten-level Chef.

In kindergarten they teach you some best practices, right? Like to say excuse me after burping and wash your hands after using the bathroom. We're doing the same thing with Chef - following some best practices, even though we're totally introductory level right now.

So here's a best practice we're using in this recipe. We're following a chef pattern called "Library cookbooks and Configuration cookbooks".

This means that we're using a handful of standard libraries created by Opscode (that's the people who make Chef) or other members of the community. We don't mess with these cookbooks, we just use them. We don't change the settings. We don't twist any knobs. We keep our hands off.

That way if the maintainer of one of those cookbooks wants to change something, they can do that, and we can upgrade to it, and it should affect us, but only in a good way. We should get the new features, the new coolness the maintainer put in, but it shouldn't break our code.

We also have one or more "Configuration" cookbooks. These are our in-house "application" cookbooks, the cookbooks that set up our stuff.

See, we know what our raw materials are - maybe a little apt, a little build-essential, some nginx, a fat dose of composer, or wordpress, or Jekyll, or whatever. Those are our library cookbooks.

But the meal comes of out how we put it all together. You know, presentation is everything. Sure, I made some rice, but rice tastes a whole lot different when you put my sausage-coconut milk-curry on top of it.

That's what the configuration cookbook is for. It puts the curry on the rice. Yum.

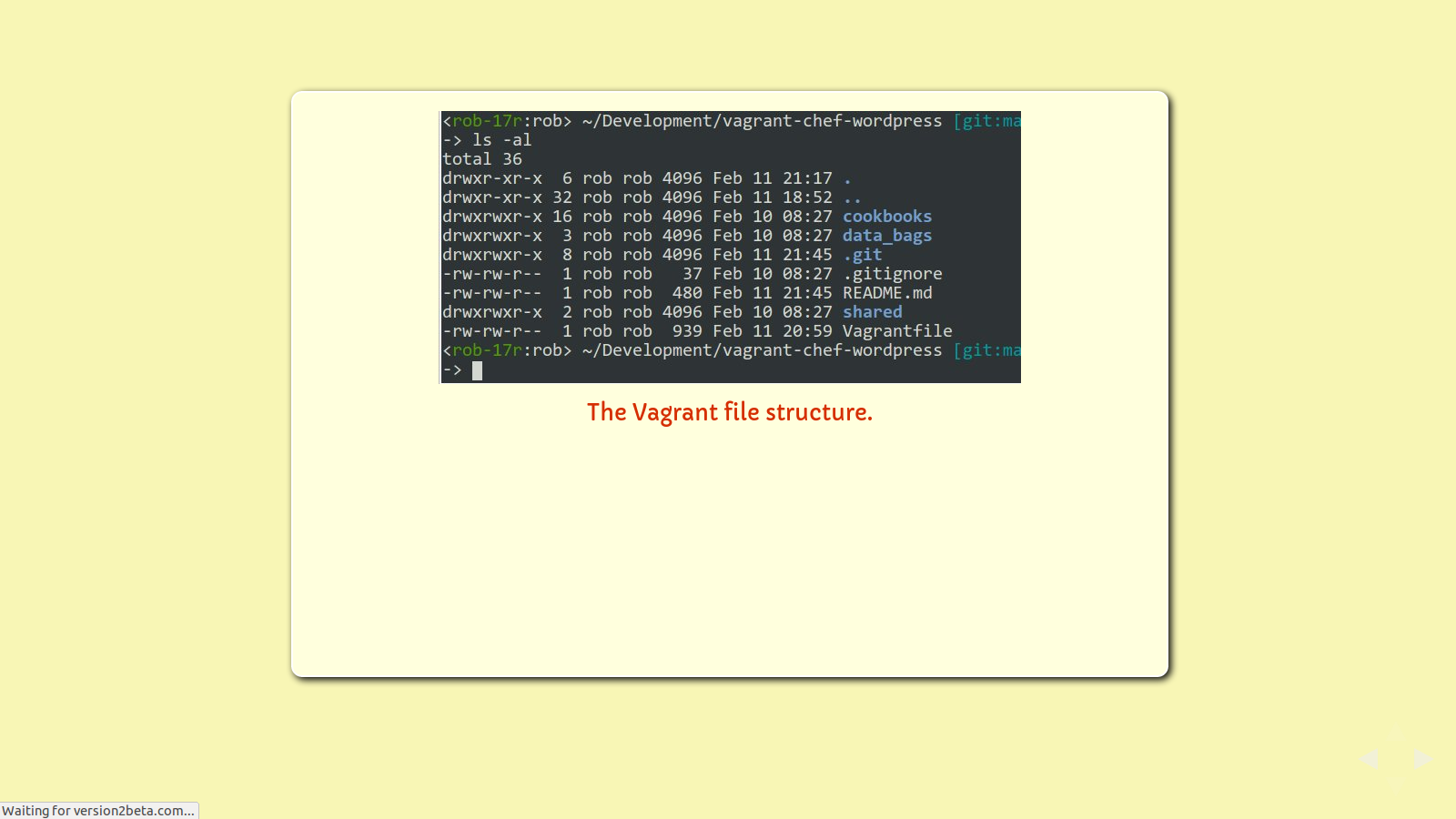

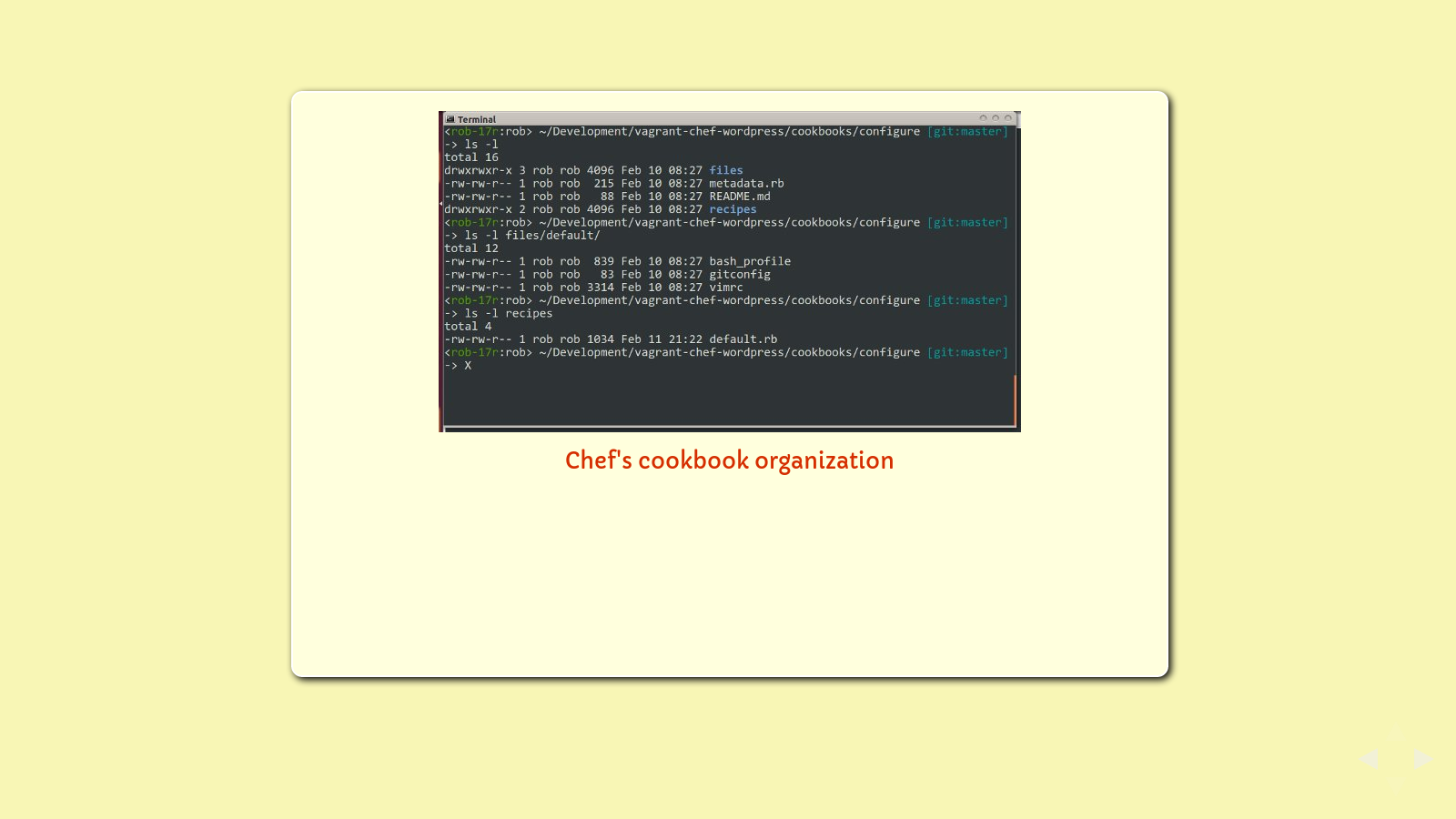

Just real quick, under a Vagrant project you're gonna have a few folders. Cookbooks live in the cookbook folder. Both library cookbooks and configuration cookbooks, all mixed up together.

Anyone here like Korean food? There's a Korean dish called Bi Bim Bap. It's a great name. Not only does it sound cool, but it exactly describes the dish. Bap means rice. Bim is vegetable. Bi is 'all mixed up'.

Files that contain data about the system as a whole like to hang out in 'databags' folder.

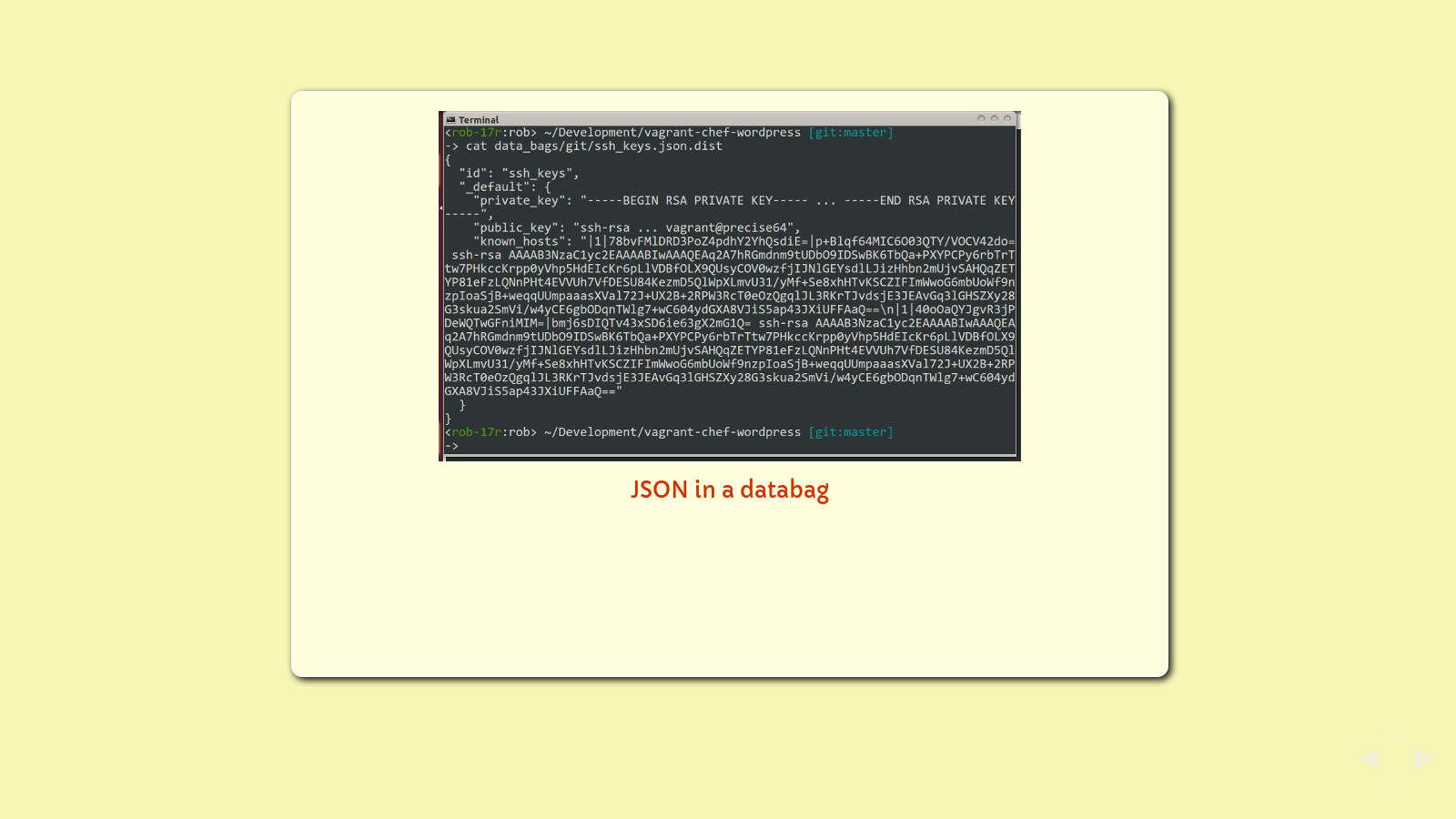

A databag is just a collect of JSON files that you can use to store information that one or more of your recipes might need. We can reference these values inside our recipes. Like this information includes a public and a private SSH key that my github account knows about. That way I can work my git repository from the Vagrant box. I don't actually do it this way anymore though, because private keys are a pain to put into JSON, so I just do it manually. If you use one of my dev environments, you'll have some choices of how to get connected to Github. Ask me about that later if you want to know.

In Vagrant, the cookbooks are straight up Opscode Chef cookbooks.

Actually, in the interest of full disclosure, Vagrant does give you the option of using other systems too, like Puppet. I'm using Chef, and I promised we'd talk about Chef. I did not promise to talk about Puppet.

Cookbooks have a README, a place to put in some attributes (you know, those tunable knobs I told you to leave alone?), a place for recipes, some resources maybe, and some providers maybe.

Here's some definitions:

A Chef RECIPE is a set of instructions describing how to install the software on one or more kinds of systems.

A Chef RESOURCE is a piece of information about the state of the machine. For example, a resource might indicate that a given piece of software is installed, or that a configuration value is set, or that a service is supposed to be running.

A Chef PROVIDER is a tool that puts the system into a given state. It's basically just a Ruby program. So a provider might set a configuration value, or tell a service to reload its configuration, or restart itself..

Let's look at a configuration recipe, since that's where all the interesting stuff happens.

[Shell: vagrant-chef-wordpress configure default recipe]

We're gonna breeze through this, and it's going to be easy, because it's just a collection of Chef standard providers. That's because Chef is a domain specific language, so we just use these little domain-specific commands to get exactly what we want.

First we include a bunch of library recipes. I did this with a little loop in Ruby, because cookbook files are in fact Ruby programs.

All of these are cookbooks that someone else wrote and someone else maintains. Some of them are from Opscode, the company that makes Chef. Some of them are from people like you and me.

By including these recipes without any more specific instruction, we're telling them to perform their default tasks. In each case, that's the install action.

Next we have the "directory" provider. We pass it some attributes and it creates the directory.

Next we have a "remote_file" provider. This goes out and gets a file from a remote location, and puts it on the virtual machine in the right place with the right credentials.

Now we have a couple of "cookbookfiles". Just like remotefile, but it comes from the cookbook, under the "files" directory.

Finally we have a provider called "link" that creates a file or folder that's a symbolic link to some other file or folder.

I started this off by telling you how simple it all is, and now I probably just went and made it look complicated. So let's back up and recap.

There'a a github repository. It's called vagrant-chef-wordpress.

We cloned it.

We changed into its directory.

We ran vagrant up.

About 6 minutes passed.

[Browser: http://localhost:8000/]

We connected to a brand-spanking-new Wordpress.

Clone my repository and use it if it helps. If you improve it, please remember to send me a pull request.

I made a couple more repositories that are similar to this one, but run Vagrant, Chef, and Composer. One of them is a nearly-empty Composer project, and the other one installs Drupal7.

[Shell: vagrant halt vagrant-chef-wordpress]

[Shell: vagrant up vagrant-chef-flask]

Let me tell you a story about my blog, version2beta.com. It's not a PHP project - it's runs from a static site generated by a Python microframework. And, of course, my development environment uses Vagrant, Chef, and Git.

A couple of years ago I decided I'd start blogging again. I felt like the Cheerleader on Heroes, I don't know if you remember that show. No matter how many times she tries to kill herself, she just keeps on healing.

No matter how many times I try to kill myself with blogging, I just keep coming back.

So a couple of years, I decided to use Wordpress. That wasn't a new decision. In fact, a couple years after I first started blogging, the platform I was using was discontinued. That was B2 from CafeLog. They dropped it in favor of a complete rewrite under a new name, Wordpress.

I built my theme, etc etc. You all know how baby Wordpress sites are made.

A year or so later I got sick of Wordpress. Actually, I got sick enough of Wordpress to do something different. At the time, I'd been learning Django, but I'd also been checking out this cool Ruby-based blogging tool called Jekyll. It is a static site generator, so it builds all of your pages in advance so your blog is way fast.

Since I was working with Python, I went looking for a Python version of Jekyll. I found Hyde. Where do they come up with these names?

Hyde was cool, but the dev environment you needed for it was a bit heavy for me. In fact, I broke my dev environment almost year ago, and never quite found the energy to go fix it. So I stopped blogging from May of 2012 until the end of January of 2013.

In January I decided I needed to fix my blog. I almost used Jekyll, which would have made sense since I've been learning me some Ruby here and there.

Apparently I still must be inspired by Larry Wall, the creator of the Perl programming language. He says the three characteristics of a good programmer are laziness, impatience, and hubris.

Fits me like a glove. I was too lazy to rebuild my blog development environment for almost a year.

Once I got over my laziness, I was too impatient to learn enough Ruby to use Jekyll. Or even look at how much Ruby I'd need to learn.

Then I polished up my hubris and built my own blog engine. In Python.

[Browser: http://version2beta.com]

It wasn't hard. In fact, it's only 125 lines of code. And it's really easy to use. And the development environment is a breeze.

So let's talk about the development environment.

My blog development environment works much like the Wordpress dev environment we already went through. I have a repository on my github account that sets up a Vagrant box with all of the tools I need: basically, Python and a handful of Python packages.

But this environment works just a little bit different. It doesn't bring up a clean, new environment. It deploys a local development version of my blog.

Let's walk through my configuration cookbook.

[File: vagrant-chef-flask/cookbooks/configure/recipes/default.rb]

My configuration recipe starts much like the Wordpress version. We start by including some library cookbooks for Python and Vim.

The next Chef command is new though. It's called "package" and all it does is use the virtual machine's package manager to install a package. My box is running on Ubuntu 12.04, so it's probably going to use apt-get. If I were on one of those other, weird versions of Linux, maybe it would use yum.

I have a handful of Python packages to install, so I'm going to use the Python package manager called pip. The Python cookbook even gives me a provider for this, python_pip.

My dev environment needs a few directories. I'll take one for the blog, one for my SSH keys, one for my Amazon Web Service keys, and one for this program you might have noticed called vcprompt. That's the git notifier I'm using in my Bash prompt. It's included in the Wordpress and Composer Vagrant boxes I made too.

Next we need to put some stuff in the filesystem. vcprompt, my bash profile, my vim rc file, public and private keys, a configuration file for s3cmd for Amazon S3, and my configuration file for git.

Then the last step tells Chef to go to Github, as me, and clone or pull my blog repository.

[Shell: vagrant ssh]

My workflow is really easy then.

I run a simple command to launch my dev server.

[Shell: python sitebuilder.py]

I create or edit my content.

I check it out in a browser.

[Browser: http://localhost:8000]

I commit my changes and push to Github.

I like it so I launch it.

[Shell: python sitebuilder.py deploy]

I think that's pretty damn easy to use. I'm happy with it.

I've been building a development environment for our developers at my day job too. It involves multiple virtual machines, many more library cookbooks, four configuration cookbooks, at least a dozen Github repositories, dozens of Python packages, preloading over a gigabyte of data into the database, and it's all written to work with Vagrant, or a virtual private server, or bare metal - whatever you choose.

I'm happy to say it works, even scaled out, comparatively.

Let's wrap it up. There are four repositories on my Github account showing off how you can make dev environments with Vagrant and Chef. Three of them are set up so that you can just clone them and go.

The first one is called vagrant-chef-wordpress, and if you clone it, you can go straight from vagrant up to picking your wordpress name. Clone it, star it, use it, make it better, send me pull requests.

The second one is called vagrant-chef-composer, and it gets you in a LAMP environment with composer and a starter composer.json file. Clone it, star it, use it, make it better, send me pull requests.

The third one is called vagrant-chef-drupal7, and it gets you the same composer environment, but this one is ready to run Drupal. Clone it, star it, use it, make it better, send me pull requests.

I really like stars, by the way. I hope to get more of them.

The fourth one is called vagrant-chef-flask, and it's my blog development environment. I recommend against working with it right now. It's really a single purpose kind of thing. My daughter Miranda and I are working on making it into a general purpose static site generator called Kobol. It's in Python, not PHP, but maybe you'll have both her and I back to talk about it sometime.

I want to thank you for listening. As always, my presentations come with a 100% money back guarantee plus tech support that is "Free as in beer". That means you buy me a beer and I give you tech support.

Talk back to me

You can comment below. Or tweet at me. I'm always open to a good conversation.