I can't teach you Erlang in 42 minutes, but I will show the three most Erlangy characteristics of Erlang: functional programming goodness through pattern matching, concurrency oriented architecture, and error handling through Erlang's "Let It Crash" offensive programming paradigm. With these three concepts, it's possible to see when and why Erlang is the right tool for your job.

I gave this talk at OpenWest in May, 2015. This is a transcript.

Erlang is a functional programming language, and as it says on the screen, functional programming is right.

That is to say that functional programming is math, which means that we can be concerned about correctness, which means we can prove program integrity.

Contrast this with object oriented programming. Objects encapsulate behavior within the context of a stateful environment. If you change an object's state, you can change it's behavior without changing the interface. You can't reason about what an object is doing unless you can nail down its state.

Here's a neat trick. Let's say you have 24 bytes of state - six 32 bit words. With those six words, you can represent more different states than there are atoms in the earth.

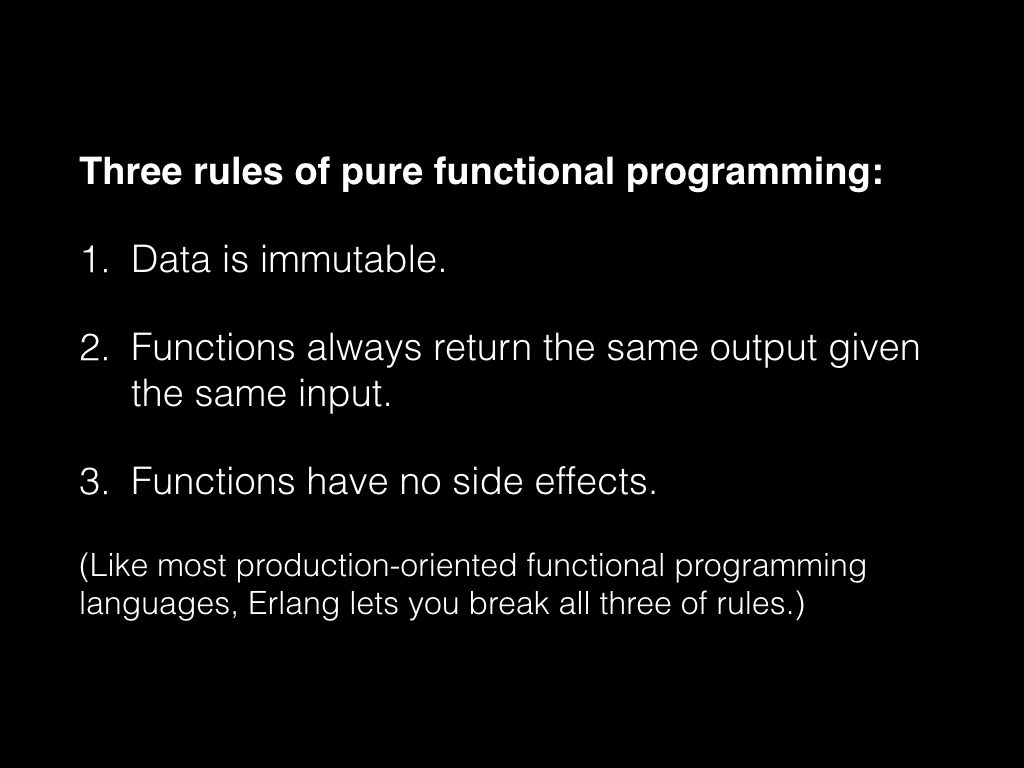

In pure functional programming, we have immutable data. It's easy to pin down data that doesn't change. It's also easy to share it when you know the other party can't change it.

We also have referential transparency - for any given input, our functions will give us the same output. This is super easy to test, and easy to reason about. Also, it doesn't matter where we run one of these functions, we'll always get the same answer. Boom, we have a cluster.

Finally, pure functions don't have side effects. You put a value in, and you get a value out. And nothing else changes. Unfortunately, while mathematics might help us reason about the world, math alone is not enough to change it. For that we need side effects.

Let's look at how Erlang does functional programming.

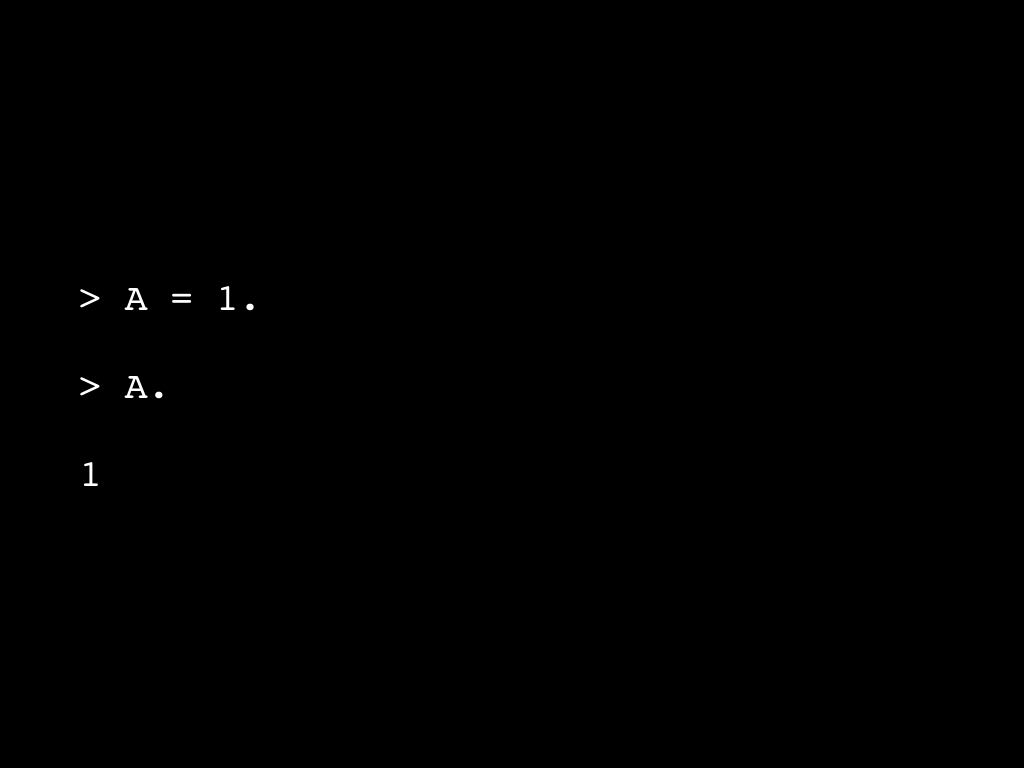

Erlang does variable assignment a little differently than we learned with imperative languages. In a simple assignment, I tell Erlang that the variable 'A' is equal to one. That's not an instruction, though - I'm not telling Erlang to set 'A' equal to one. I'm merely informing Erlang that 'A' is equal to one.

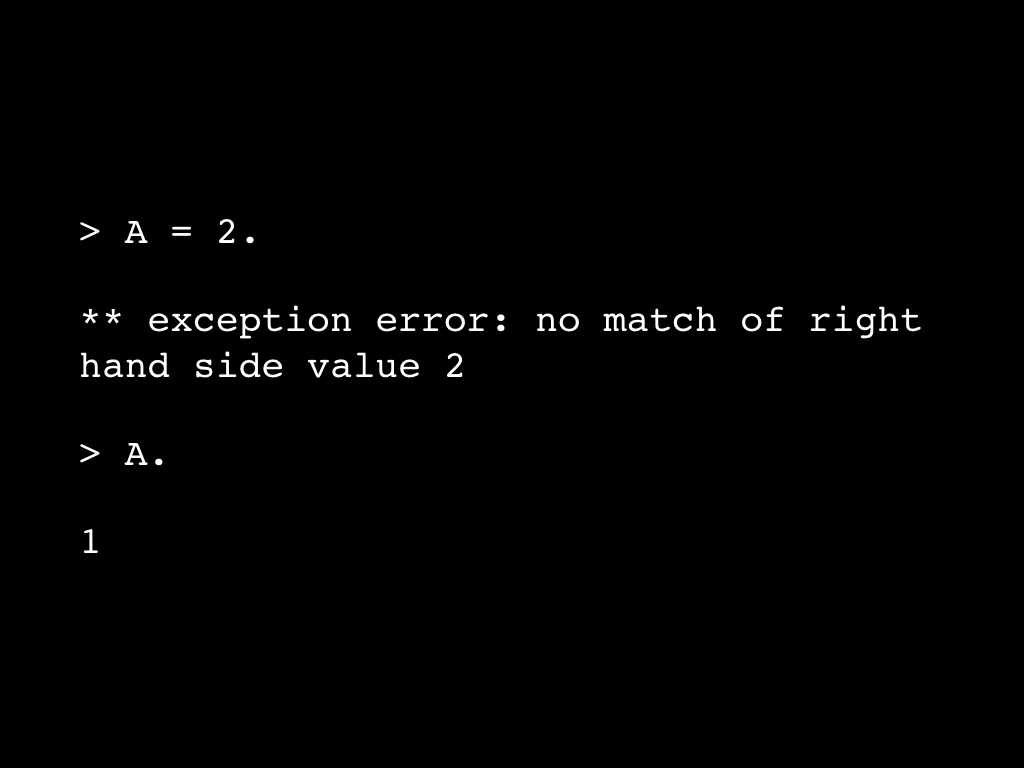

You can see the difference when I try to tell Erlang that 'A' isn't equal to one anymore, now it's equal to two. Erlang will politely inform me that I'm wrong, that Erlang already knows what 'A' is equal to, and it's not two.

Note the way that Erlang talks about this. "No match on right hand side value 2." It's not an assignment, it's a match. Erlang is looking at the two sides of my equals sign and trying to see how they match. In this case, they don't, so Erlang gives an exception.

The only reason Erlang let me get away with telling it 'A's value was because the first time around, Erlang didn't know what 'A's value was. 'A' was unbound. But then I gave Erlang a logic statement, and from that, Erlang could infer that the unbound variable 'A' had a value.

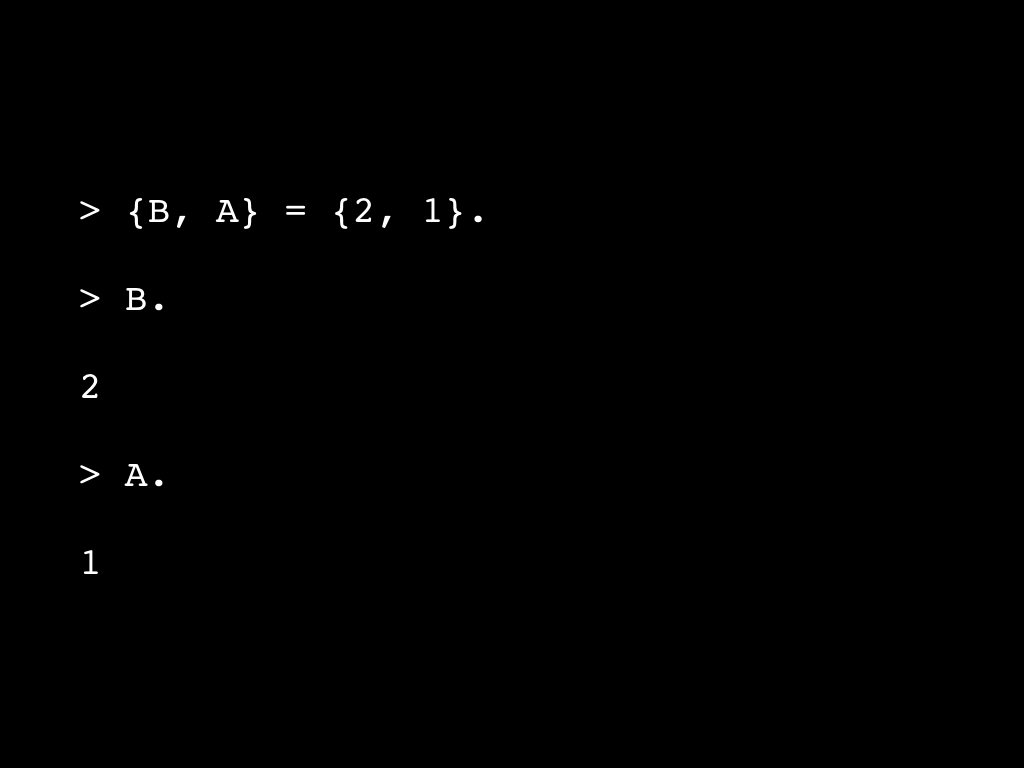

Erlang will do matching even when it needs to unpack values to do so. However, it's important to note a couple of things. First, the unbound variable needs to be on the left side of the equals sign. Second, bound variables still have to match or you're going to get an exception.

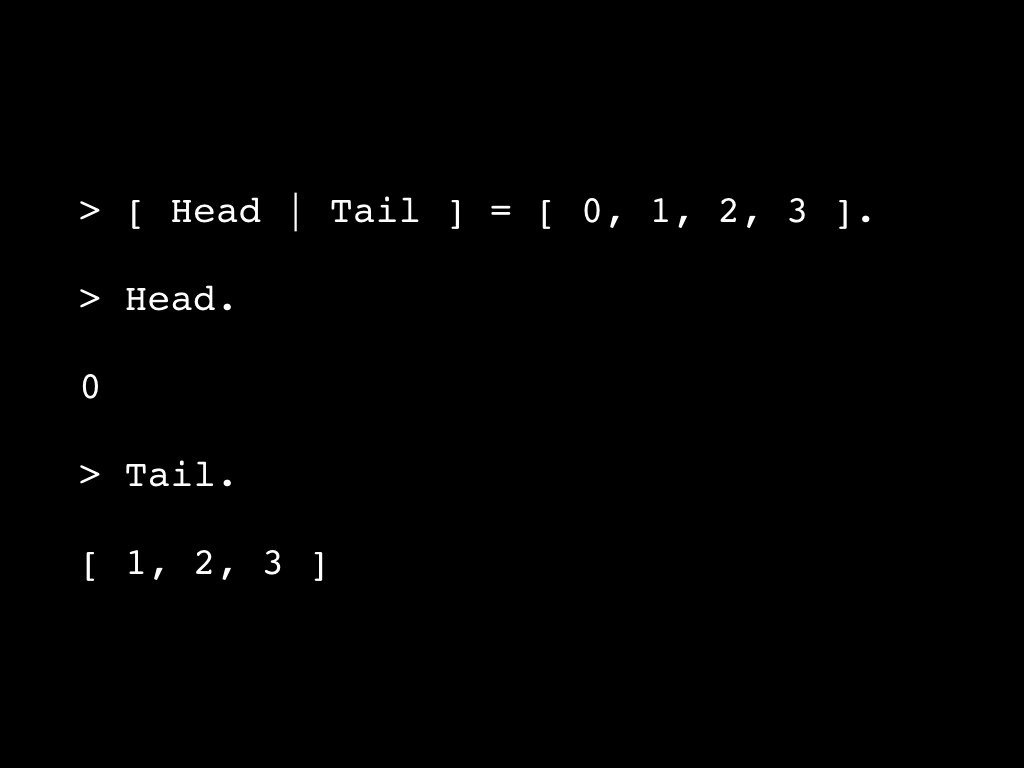

Erlang does a special unpacking job when it comes to lists. If you've ever studied Lisp or Scheme or any of the derived languages, you might be familiar with the terms CAR and CDR, referring to the pointer for the first element of a list, and the pointer for the second element, which carries with it the links for the rest of the list. Erlang refers to the Head and Tail of a list similarly. Head refers to the first element, and Tail gets you the rest of the list.

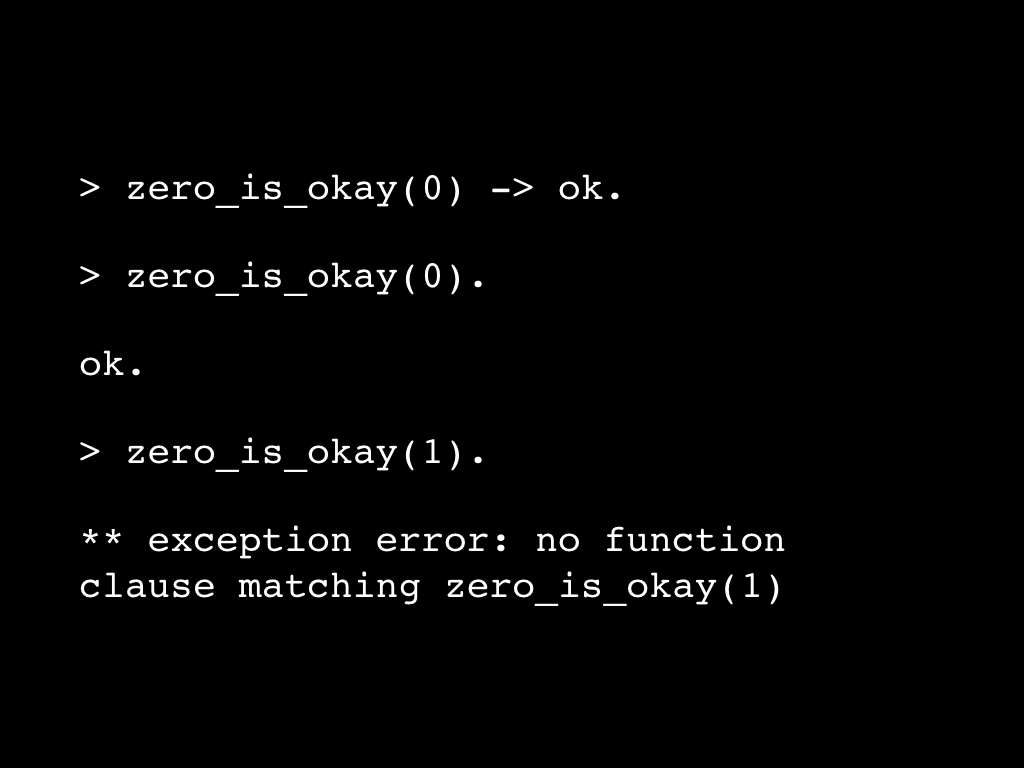

Erlang does the same kind of pattern matching and variable binding when defining functions. If we define a function with an argument that's constant, like zero in this example, Erlang will only recognize the function when there is a match on that constant. Anything else will crash and burn.

Just as an aside, this example returns a value called 'ok'. That's not a built-in value or anything, it's what Erlang calls an 'atom'. Erlang's atoms are a 'literal' data type, where the name and the value are the same. In Ruby, a similar data type is called a symbol.

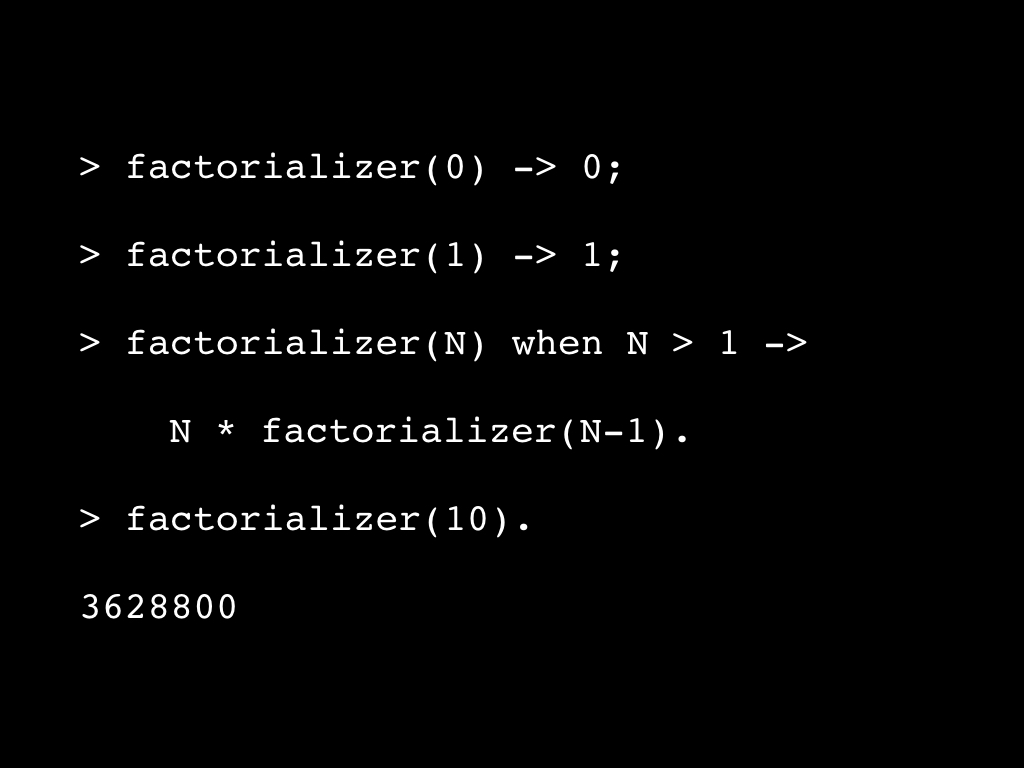

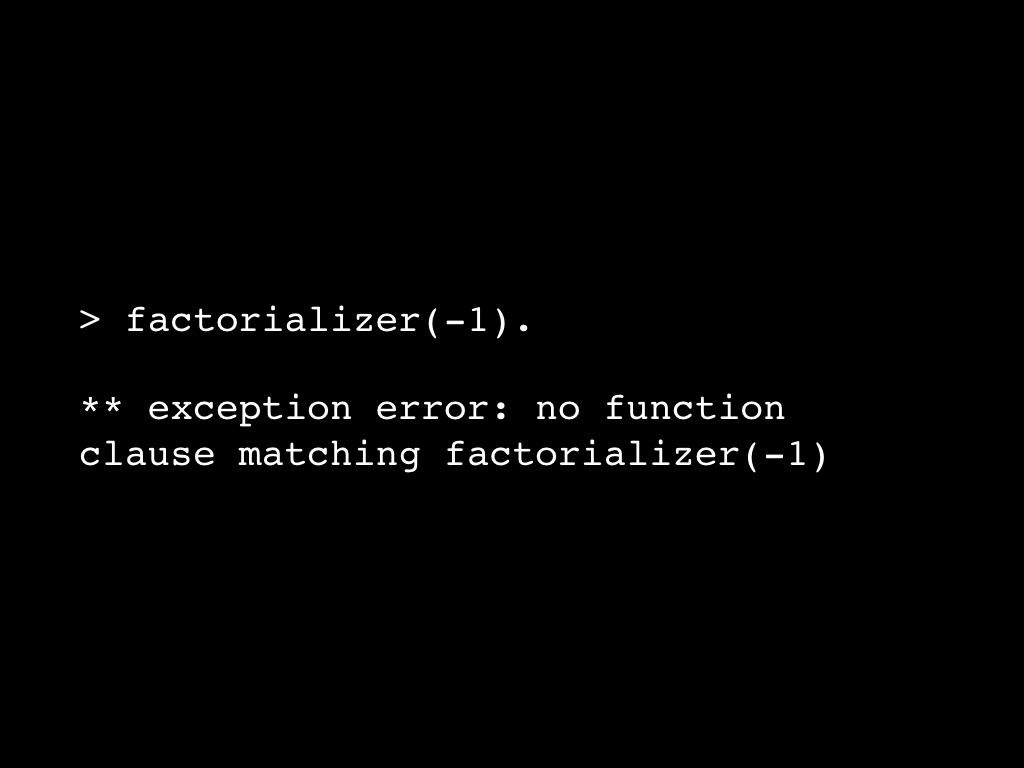

This pattern matching business becomes more useful when we add in Erlang's conditional dispatching. We can define the same function name with the same number of parameters in several different ways, and Erlang will use only the one that matches.

In this example, we're defining three different versions of the same function, one for when the input value is zero, one for when the input value is one, and one for when the input value is greater than one. The "greater than one" version of the function is particularly interesting. In that case, we're binding the value provided to a variable, but we're also using a guard that says this version of the function only matches when the value provided meets a given condition.

Just like our 'zero_is_okay' function, if we provide an input value that doesn't match any of our declared functions, we're going to get an error than we don't have a matching function.

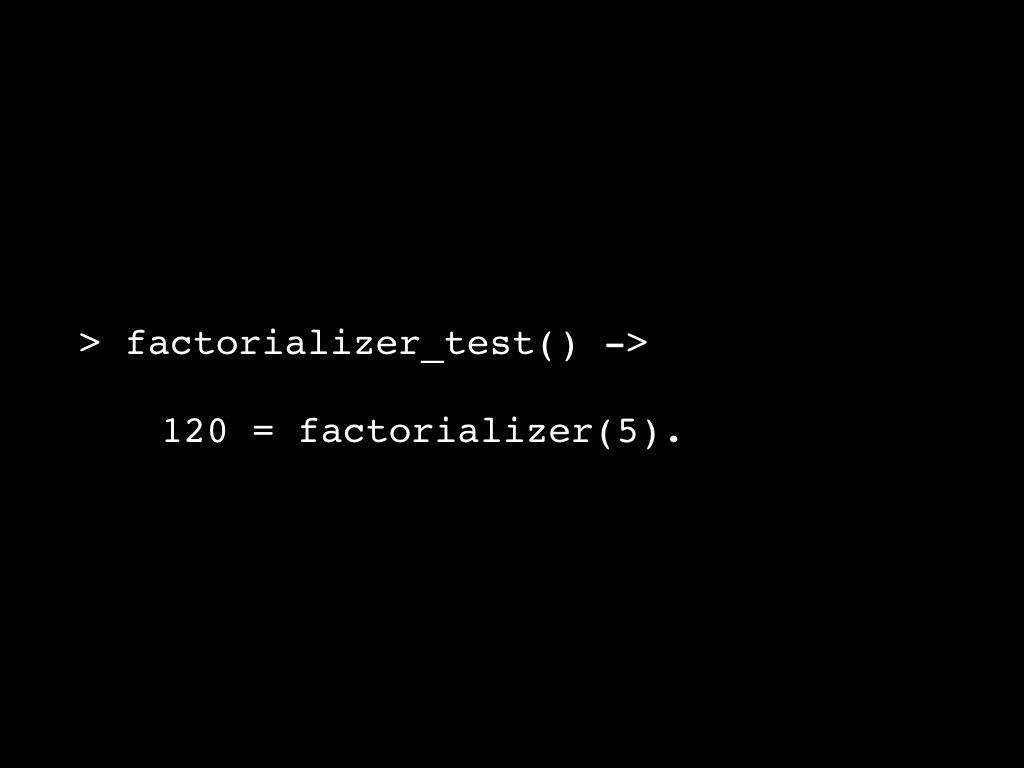

While Erlang provides a very rich assortment of test environments, the easiest way to write a unit test is just to create a match that should be true. Erlang's test libraries will catch the exception if the statement turns out to be false.

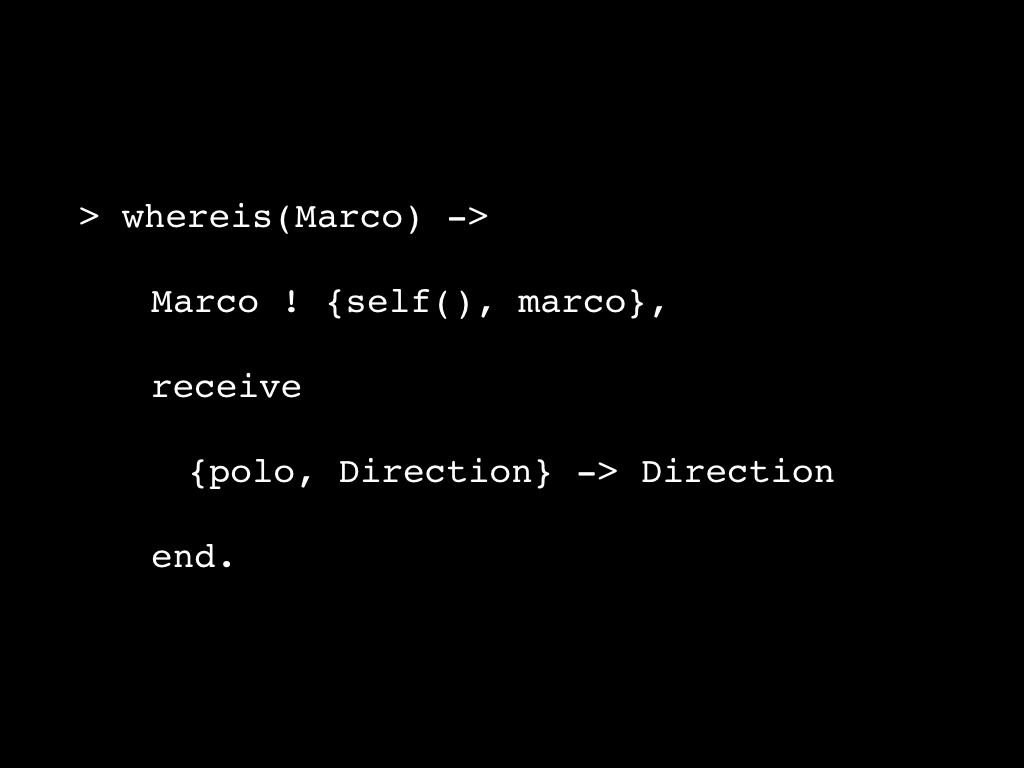

Erlang is concurrent and uses message passing to communicate between processes. It uses pattern matching to handle incoming messages from other processes. In this example, we send a process we know as Marco a message that is our PID and the atom "marco". Then we wait for Marco to reply with a tuple of the atom "polo" and the direction we should move. Erlang is going to ignore any messages that aren't a tuple starting with the "polo" atom, but when the tuple does start with "polo", it will take the second part of the tuple and bind it to the variable Direction, and return the value of that variable.

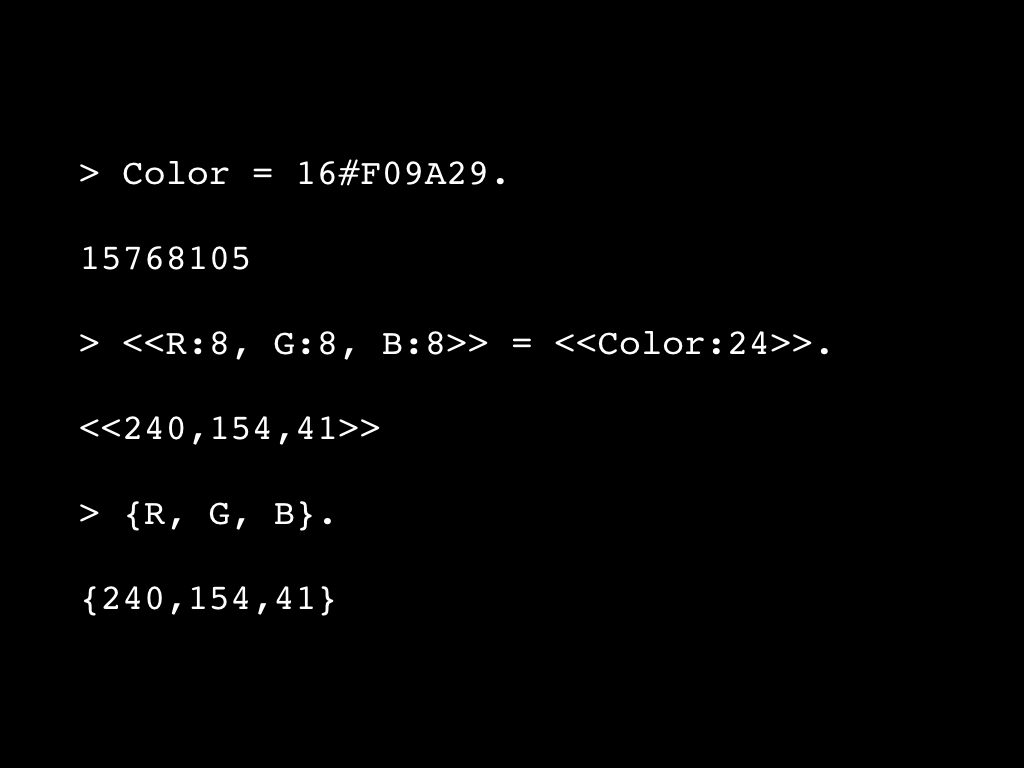

Erlang's support for binary operations is extremely powerful, and it is also based on pattern matching. In this example, we are binding a base-16 number to a variable called "Color". You might recognize this color as orange. But then we ask Erlang to unpack Color as a bitstring - that's what the double brackets do - on 24 bits of space and bind each byte to a variable. Now we have the Red, Green, and Blue components of that color. This kind of pattern matching in Erlang is tremendously useful for serializing and deserializing data, no matter where it's coming from.

That was a quick overview of Erlang's version of functional programming, but in just a handful of examples, we've looked at immutability, referential transparency, pattern matching, recursion, function definitions, multiple dispatch, message passing, and bitstrings. That's more than half of Erlang's syntax in about ten minutes.

Notice how every single code example relied on pattern matching in some way?

I do have a confession to make. None of the code in this presentation works as presented. The code is all good, it's just that I've mixed expressions with statements. Erlang's REPL, the erl shell, lets you type expressions but not statements. Erlang programs are pretty much all statements, mostly statements defining functions. So in order to run the code samples, you would have to type the functions into a module and then compile and load the module so that you can reference them in the shell. It's awkward. Actually, the Erlang shell also offers a way to do this, but in my opinion, it's even more awkward.

Concurrency

Let's move on to concurrency and nail down some definitions.

Distributed computing is when our concurrent processes work together to solve a problem.

Concurrency is when more than one process is running. We do this all the time at an operating system level, and often do it at a programming level.

Symmetric multiprocessing means that we can schedule processes and threads across more two or more processor cores.

A process is a sequence of programmed instruction, either single- or multi-threaded, that a computer executes.

A thread is a single sequence of programmed instruction that a computer executes sequentially. Multi-threaded processes execute more than one thread at a time.

In a lot of languages, we consider threads to be lightweight and processes to be kinda heavy. Threads can get started up quickly but processes are slow. Threads tend to share memory and processes tend to be isolated from each other. Threads use a little memory and processes use a lot.

Erlang is multi-threaded, but Erlang threads act more like processes so that's how we refer to them. Erlang processes share nothing, and can only communicate with each other by sending messages. They're isolated from each other, so if one process dies it won't take out other processes. Many people say Erlang feels like an operating system because processes are as isolated in an Erlang program as they might be running from a Unix shell. In fact, Erlang is more like a bunch of Unix shells. Erlang processes behave the same regardless of whether there is a machine boundary, so it's trivial to scale from one server to many.

On the other hand, Erlang processes still act a lot like threads, and this is one of Erlang's greatest advantages. Processes are tiny, using as little as 618 bytes of memory. It's not unusual to run tens of thousands of processes on a single machine, and it's possible to run millions.

Joe Armstrong, one of the creators of Erlang, has said that Erlang is more object oriented than most modern object oriented languages. I asked Robert Virding, another one of the creators of Erlang, about this and he rolled his eyes. But Joe may be right. Alan Kay came up with the term Object Oriented Programming, and he's also said that he's sorry he coined the term "objects" because the big idea is "messaging", not "objects".

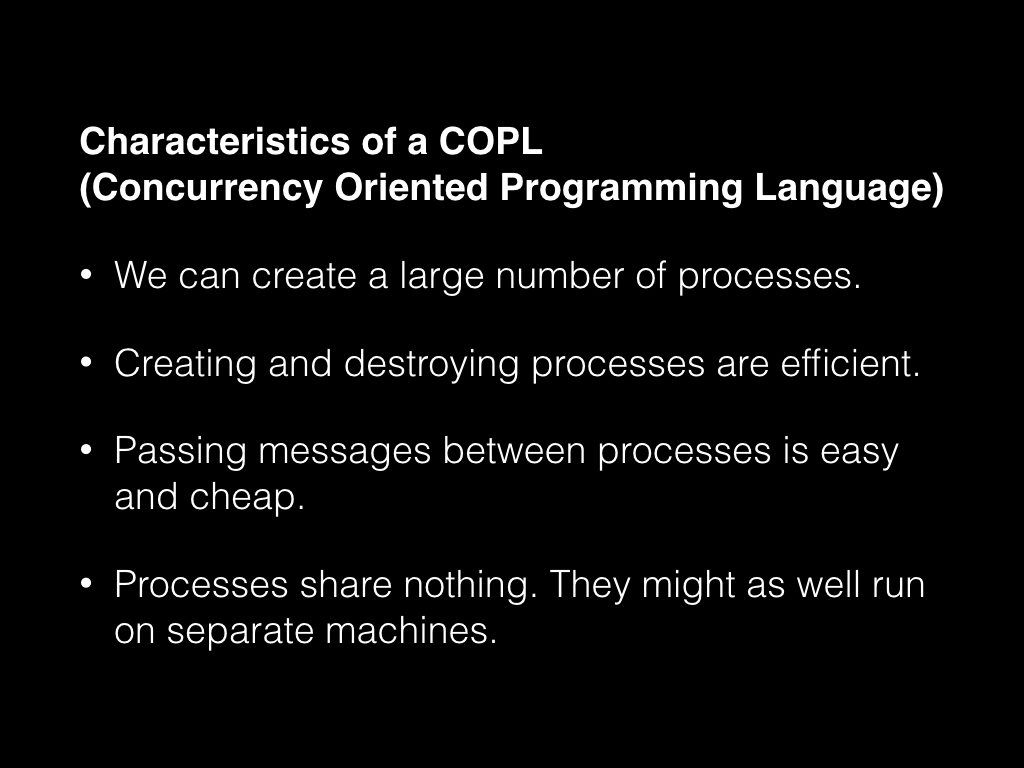

Either way, Erlang's primary abstraction is not the object, it's concurrency. Joe Armstrong calls it Concurrency Oriented Programming, and says that Erlang is a Concurrency Oriented Programming Language.

When we're programming in a concurrency oriented programming language like Erlang, we can some nice benefits.

- It's easy to distribute our systems across multiple machines. We just start the processes up somewhere else.

- It's easy to scale a system simply by adding more machines and redistributing our processes.

- It's easy to make our systems fault tolerant by breaking them up across multiple machines and making some of our processes into supervisors that watch over the other processes and clean up after them if they die.

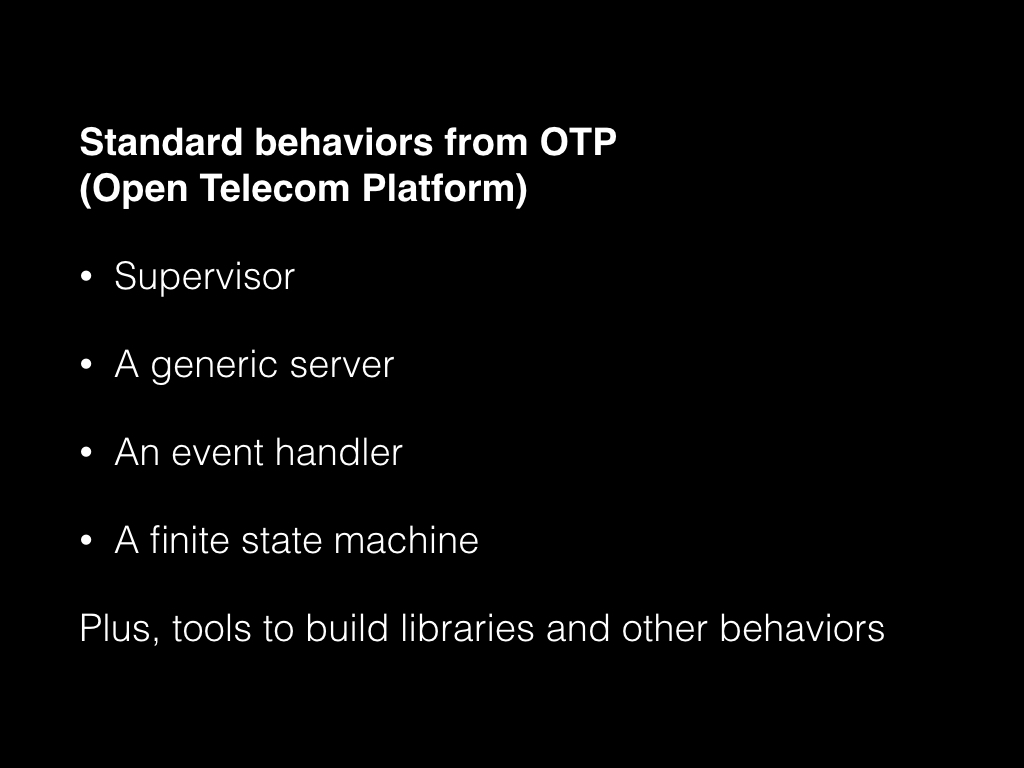

Erlang also comes with the Open Telecom Protocol, or OTP for short.

The name of this library is possibly one of the least fortunate parts of Erlang's history, at least outside of Ericsson where Erlang was originally developed. It reinforces that Erlang comes from the telecom industry and suggests that it's a tool primarily for telecom. When newcomers hear that most Erlang programmers use OTP, it suggests that most Erlang programmers are doing telecom work, or work that's very similar to it.

Erlang is not limited to telecom work. OTP is not limited to telecom work. Just saying, they abstracted telecom out of the library, they probably should have abstracted it out of the name too.

As long as I'm complaining about OTP, I'll add one more. Christopher Alexander's book A Pattern Language came out in 1976, and the Gang of Four book on software patterns came out in 1995. OTP was open-sourced in 1998, and Erlang's developers at Ericsson failed to predict that what they called behaviours, the rest of the world would call patterns.

Aside from that, OTP is great. These are solid libraries with nearly two decades of proven use in large scale, highly concurrent applications. Use it.

Let it crash

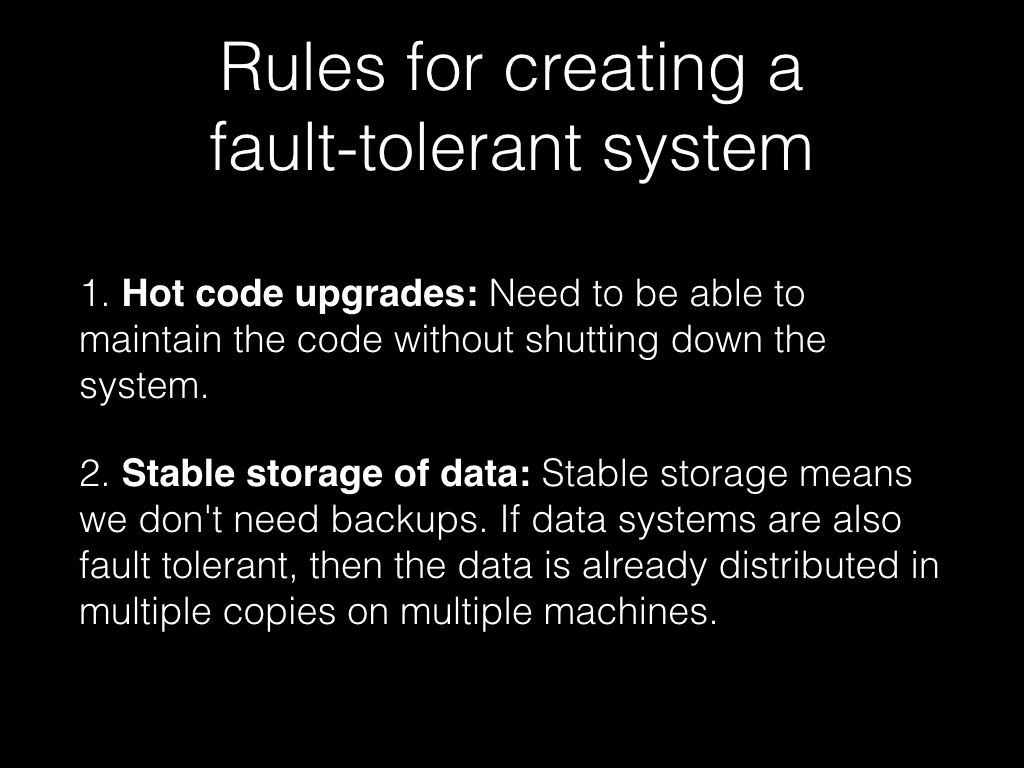

In a talk called "Systems that run forever, self-heal, and scale", Joe Armstrong lays out six rules for creating a fault tolerant system. Spoiler alert: Erlang is designed around these.

While Erlang does hot code swapping and the Erlang ecosystem has strong support for fault tolerant data persistence, both of these topics are out of scope for this talk.

I'm pretty good at scope creep though, so I will add just a couple things here.

On the surface, Erlang's hot code swapping is cool, but feels like something they forgot to update over time. Erlang lets you load code in two versions, the running version and the new version. You switch from the running version to the new version by just calling the code. It's an implicit reload. When you want to run explicit code swapping, Erlang has some functionality that'll help with a lot of that. It's a little bit like Ruby's Rake, but it's also sometimes referred to as the 9th Circle of Erl.

So yeah, Erlang isn't perfect. In fact, a lot of people complain about Erlang's tool chain. As it happens there are a lot of incredibly powerful tools for Erlang, but the community around them is small and it can be hard to find and learn them.

Fault tolerant data storage is solid, though. Besides the Erlang-specific ETS, DETS, and Mnesia data storage options, my two favorite NoSQL databases are written in Erlang - CouchDB and Riak. Plus there's RabbitMQ, which is also written in Erlang, and while a message broker is very different from a database, RabbitMQ is a fault-tolerant, stable method for storing and distributing messages.

Isolation and concurrency are the foundation for Erlang processes, as we've already discussed.

When I started thinking about which features of Erlang are idiomatic, which features are so integral that removing them would denature the language, concurrency was first on my list. Joe Armstrong talks about Concurrency Oriented Programming Languages and a style of programming he calls Concurrency Oriented Programming. Robert Virding teaches about the fundamental difference between concurrency through shared memory, the way most programming languages do it, and share nothing concurrency. Erlang, of course, shares nothing and this is the foundation of isolation in the language.

Every program has bugs. Extremely stable systems don't expose their bugs during the useful lifetime of the software.

Erlang does it different. It crashes. All the time.

Marvin Minsky, the founder of the MIT Media Lab, wrote a paper once called "Why programming is a good medium for expressing poorly understood and sloppily formatted ideas." It's a lot harder to know what we're supposed to do as programmers than it is to tell computers how to do it. We can specify the parts we know pretty easily. It's the vast universe of unknowns that bite us in the ass.

I have a guideline I use for programming that I call "de Raadt's First Rule". I'm pretty sure I heard it from Theo de Raadt directly, but I haven't found anyone else attributing this to him so maybe I have it wrong.

Theo de Raadt is the founder and leader of a couple of highly secure software development projects, OpenBSD and OpenSSH. He taught me that the first rule for writing secure software is to make it do what it's specified to do, and only what it's specified to do. Security exploits rarely take advantage of properly functioning code; they exploit software that's doing something it wasn't supposed to do.

In some ways, you could say Erlang embodies this approach. Here's another quote from Joe Armstrong: "Exceptions occur when the runtime system doesn't know what to do. Errors occur when the programmer doesn't know what to do." In Erlang we can code to the specification, and simply let anything outside of that specification be an exception that crashes the process. We don't have to defend against every exceptional condition; we can simply tell Erlang what's acceptable and let everything else crash.

If it's not right, we can let it crash.

Erlang's strengths

To be perfectly honest, I've had a hard time wrapping my head around Erlang. I got the syntax but missed the gist.

I've heard about the telephone switch at British Telecom programmed in Erlang that reportedly achieved nine nines of uptime. Impressive, right?

I've heard about the case study that says Erlang programs are 80% smaller than the same functionality written in C++. That also sounds amazing, like I can do five times as much in the same amount of time.

I also knew that Erlang came from Ericsson and the telecom industry. With amazing pattern matching in a functional programming language, it seems like Erlang would be a great choice when I'm doing heavily network-oriented programming. An API router. A proxy server. Messaging.

I had trouble seeing how amazing uptime and code base reduction fit into the bigger picture. It's like this: a big part of the savings (27% in the study I just referenced) comes from coding for the successful case. And a big part of the uptime is that we let it crash when we don't get the successful case. It's what we do after the crash that makes the system fault tolerant, and not just incredibly stable. And sure, Erlang is good at network programming, but that is a side effect of Erlang being good at a lot of things.

Now I see that this is the big picture, the parts of Erlang that make it Erlang.

At the lowest level, we have Erlang's functional foundation with immutable data and program flow from pattern matching for the successful case.

A layer up from that we have Erlang's concurrency, with supervisors watching workers and cleaning up any messes they leave behind, and OTP providing boilerplate implementation of our most useful concurrent patterns.

Finally, there is Erlang's "Let It Crash" mentality - an acknowledgement that failures happen, and we can deal with them.

The world is a stage and we are all actors upon it. We talk, we grow, we fail, we heal. We're hopelessly separate, but we find ways to connect. We can't change the past, but we can take care of each other.

And that is how we program in Erlang, too.