Update: CodeMesh video of my talk is up.

This is my talk for Code Mesh 2015 in London, basically as a transcript but more like what I intended to present rather than the slightly more ad-libbed version I actually gave. The abstract I submit reads as such:

We started with 42 Oracle tables, 5200+ configuration values, no default values or templates, logical inconsistencies and circular dependencies, on-boarding times running as long as 10 months, a 1.5 million lines of legacy code, and advice that anyone who tries to redesign our configuration system will be gone within six months. Our solution is a custom-built functional data store with inheritance, flexible projections, backward compatibility with the legacy code, and a Lego™-like framework for building tools. Plus, I still work there. Come learn how we did it.

Talk objectives:

I'd like to share how we replaced a complex, "organically-designed" configuration system that we couldn't reason about with a immutable, accretive, functional, time-variant data store based on event sources and command query responsibility segration. We're particularly happy with our choices to project views into Oracle and to treat Oracle as an event source (which gives us backward compatibility with our legacy code), and to allow queries that compile data from multiple documents (which gives us reusable configuration templates).

Target audience:

Programmers and managers interested in applying functional programming concepts to data stores.

Key concepts

Will Byrd (@webyrd) suggested an important idea to me. When preparing a talk, perhaps a case study in particular, consider what you would want someone who attended your talk to reflect back to you afterward. If you were to ask what someone got from your talk, what do you want to hear in their reply?

Here are the concepts I most want to hear reflected:

- Manage complexity first. Functional first programming reduces complexity.

- Patterns bring surprising wins.

Will's contribution improved my talk substantially. Here are some comments from attendees.

OC Tanner does employee engagement through recognition and appreciation awards. Before I uncover some warts, let me just say we do appreciation well. In fact, we created the field when Obert C. Tanner - O. C. Tanner - went off to Berkeley in the 1930's and earned a Ph.D. in the philosophy of appreciating people. We are the largest company of our kind, with offices all over the world - including right down the road from here in Essex. 28 of the companies on the Fortune 100 Best Places To Work list use our software. We're one of them - we're #40 on Fortune's list of best places to work.

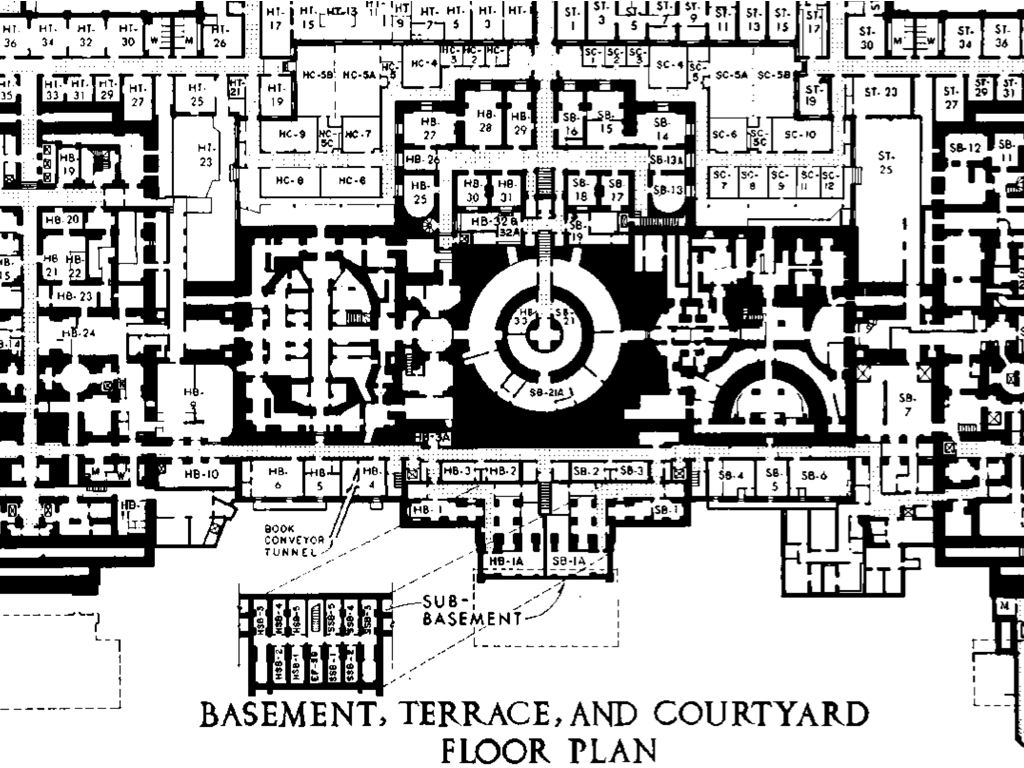

OC Tanner has grown over the years primarily by saying yes to customers. As our capabilities have increased, we've tacked additions on to our facilities like old houses used to get more bedrooms as the family grew. Our basements are a good example: we have seven, and they aren't connected to each other.

I heard a story about a woman who started her first day of work by going through our half-day orientation session, and then asked if she could skip lunch and go say thank you to the friend who had recommended her. She got directions to find her friend's team, down in one of the basements. The person leading the orientation didn't expect to see her again, since she was supposed to report to her manager after lunch. When she didn't report for work after lunch, her manager assumed she had been a no-show for the whole day. Late that afternoon someone found the poor woman in one of the basements, hopelessly lost and crying.

This is what our software is like too.

I mean that our software has grown organically over the years, by saying yes to customers. Can I have this new feature? Yes. Can you make the software do things our way? Yes. What if we want this to be royal blue? Yes. Option by option, tacked on like a new tower on the castle, with a royal blue turret on top. Or purple. We can do purple too.

This is where much of the complexity in our software came from. I suspect we're far from unique in this. Organic growth makes things more complex. At least that's what Alan Watts says.

When I started, my new boss put me in charge of the team responsible for configuration tools on the second largest software platform we offer. He explained to me that there were umpteen hundred settings, and onboarding required individually setting every one of them correctly, and that was a big reason why our onboarding process was running as long as ten months and we need 175 people to do it. My team was responsible for the monolithic web app used by those internal customers to manage those settings. Oh, and the only developer on that team was out on maternity leave and we didn't know when she'd be back.

He also told me that there is a standing prediction in the office that anyone who takes on configuration would be gone within six months.

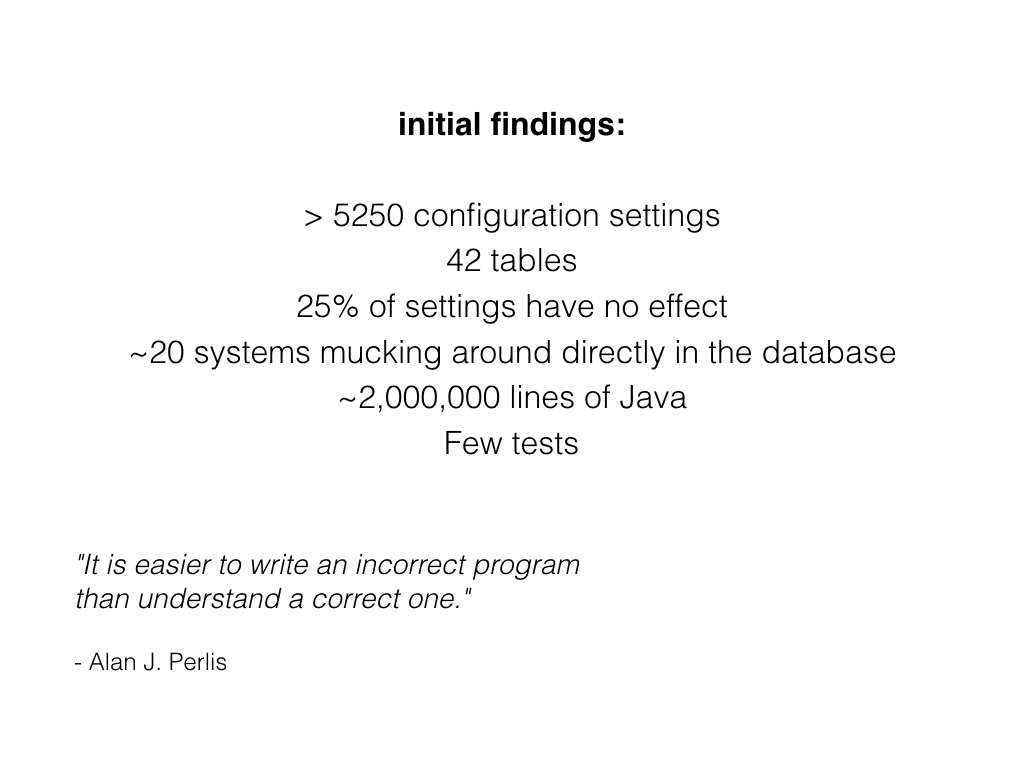

Here are a few statistics from the beginning of the project. I found it intimidating, but frankly it's probably a pretty typical system.

We have about 75 programmers on staff, most of whom are carving monolithic platforms into microservices. Our software is complex, but you've probably worked software just as complex.

My team is working on a better system for configuration and configuration management, but the process we've been working through would be pretty much the same regardless of the project.

Our configuration data is poorly organized, hard to find, and hard to reason about. It's like a kitchen junk drawer. Most kitchens have one. That's how common our problems are.

Our legacy code happens to be written Java, but that doesn't matter. What matters is there is a lot of it, and it doesn't have many automated tests. We can't fix it all at once, so we have to work with it. We have to support the legacy system.

Reducing complexity is my "zeroeth law of programming", so my goal on this project, and on every other project, is to reduce complexity.

The two tools I use most to manage complexity are design patterns and functional programming. Design patterns prune a project back to a common shape, and functional programming makes it predictable.

I'm not going to cover all of functional programming in one slide so instead we'll talk about a pattern I like called functional-first programming.

But first, design patterns.

You're probably here because you think you might have problems that look something like our problems. If we're all lucky, I might have solutions that look something like the solutions that are going to solve your problems.

That's what a design pattern is. Design patterns are generalized solutions to generalized problems. They help us understand our problems quickly, and the give structure to our solutions early in the process. Design patterns help us reason about our project right away.

Pretty much everything I'm going to talk about today is a design pattern. Functional-first programming, event stores, command query responsibility segregation, prefix tries, static site generators. We didn't do anything new. We looked at the problem we were trying to solve and found patterns other people discovered that matched our problems. Then we took established solution patterns and made them fit our needs.

One of the really neat thing about design patterns is that they bring win with them. If I had sat down to create goals for this project without first having some patterns in mind, I would have come up with a good list. But the patterns we chose informed our design goals tremendously.

Choosing the right patterns not only helped us solve the problem, they raised the bar on what we could expect from our solution.

I stole the term "functional first programming" from Don Syme, without asking him and without checking to see if I'm using it the way he intended. If I am, it's only because he named it really well, because when I heard the term I thought "That's what I'm doing!" I probably owe him an apology.

My version of functional first programming goes like this: First code everything that's possible to do without side effects. Then code the side effects. The first part should be purely functional, easy to test, easy to reason about, and maybe even provably correct. The second part is just side effects, which probably means it all depends on IO libraries that someone else wrote and tested. There's a good chance you won't even need to unit test your side effect code, which is a good thing because we hate writing mocks. Plus, your interfaces to the outside world are now strictly modular, so changing an interface or a database is very concise.

You can do functional first programming in almost any programming language, including object oriented programming languages. Gary Bernhardt has a great talk on that called "Imperative shell, functional core". But using a functional programming language makes it easier.

I like mostly pure functional programming languages. A powerful language might let you do all sorts of amazing manipulations in a computer, and a flexible language might give you tremendous choice in how you solve any given problem. Those languages have their place, but for managing complexity I always prefer a strict, opinionated, constrained language. Power and flexibility tend to lead to increased complexity.

It turns out choosing a language is a lot like choosing a design pattern. The languages we use change the way we think about a problem. My team could have solved our configuration issues acceptably using only Java, but choosing to use an actor-based concurrent programming language created opportunities we don't get with Java.

When we started, I thought we were building a specialized configuration service. It took me a month to see that we were actually building a NoSQL database - a key-value store. When I finally realized this, I went to my CTO and asked him why he approved a project to build our own database.

If I'd realized this sooner, I'm sure I would have dropped the project and tried to figure out how to do it with a generic NoSQL database. The jury is still out on whether that would have been a better move, but by the time I realized what we were doing we already had design goals I couldn't meet with any of the NoSQL databases on the market.

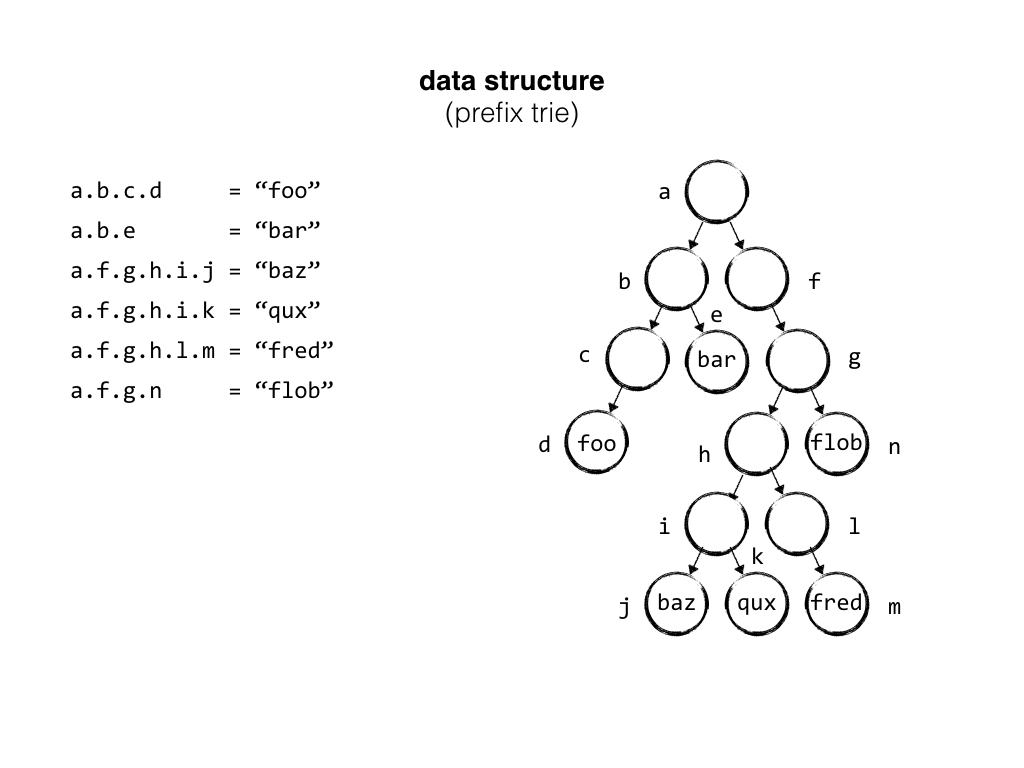

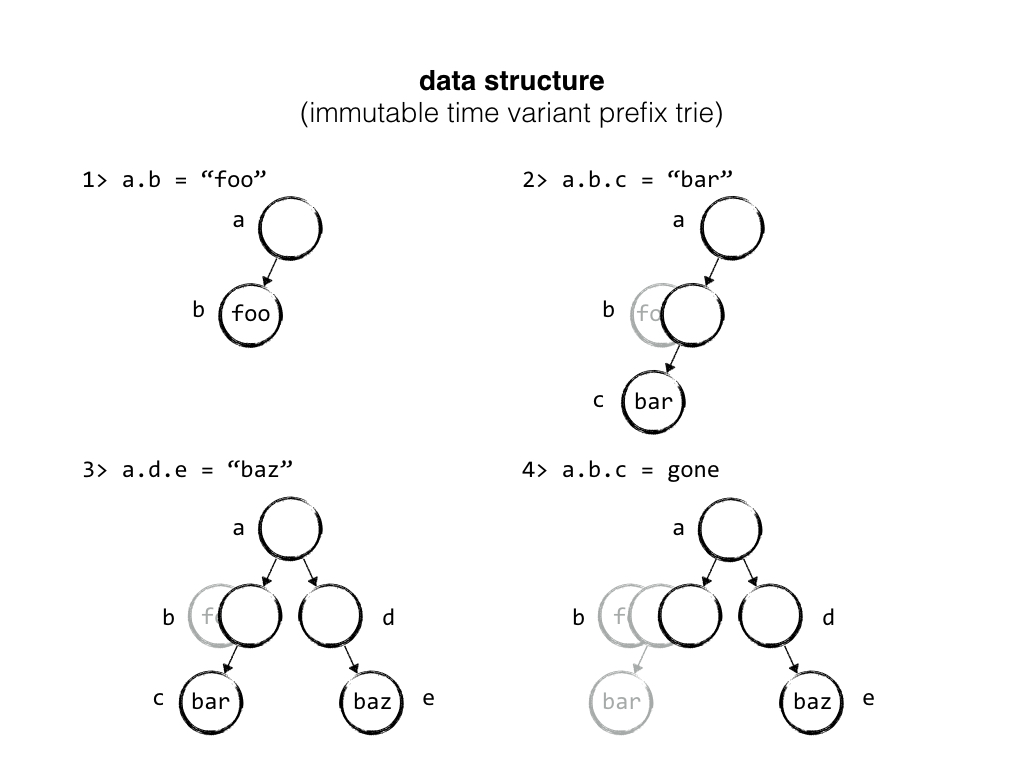

Our data structure is a basically a trie, which is actually called a "trie" because it comes from the word "retrieval" but I prefer "trie" to distinguish it from a "tree" that comes from the word for a big woody plant.

Tries help you find things quickly and store things compactly by building a tree that shares prefixes. In our case, nodes could represent a dotted-notation key. We map each node to an Elixir process - an actor - and give it responsibility for processing events regarding its state, persisting new events, and sharing new events across a cluster.

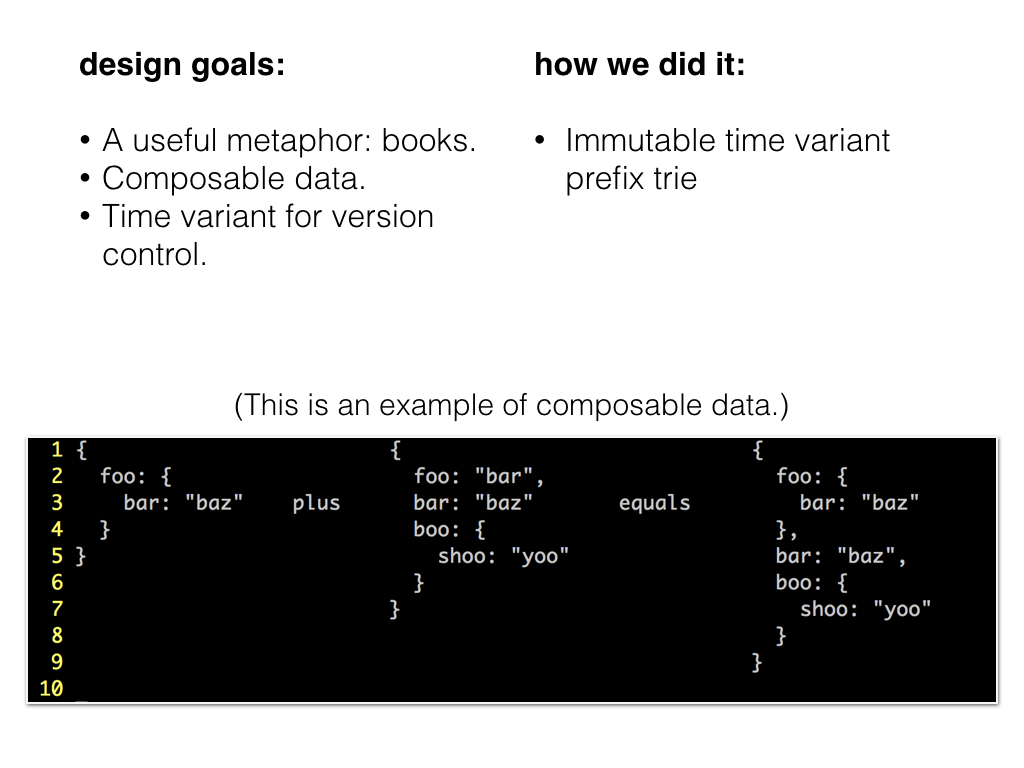

Our old system doesn't have the concept of default settings. Every new customer needs to have every configuration setting established by an implementation specialist. With our new system, we want to get most settings from a book of defaults, and only get involved when a default setting doesn't fit the customer.

This is where our book metaphor comes in handy. We have a book with system-wide default settings. We have books with the default settings for various option packages. The customer has a book, and each user can have a book.

Composable data is like stacking those books. The user's book overrides the customer's book, which overrides the books of default settings. Conflicting values from less specific books are ignored in favor of the more specific book.

We have a special situation though. Although many of our customers can simply use the default values in the current version of each book, some of our customers want to go through a change review process, so we can't willy-nilly update the default books without warning them. We need to maintain previous versions of each book.

If we look at our prefix trie again, this time I'll show that every node contains not only its current state, but also all previous states of the node. We keep the value of the node over time in a list. When someone asks for a setting without specifying the version, we give them the most recent valid version. But if they specify any specific version, we can give it to them.

Under the old system, when a developer needed to create a new configuration setting, he or she created a row, or maybe a table, and stored the data there. Documentation typically sucked - the name of the table and the name of the column along with the code. Other developers that needed to interact with that setting would figure it out from those clues, or ask the team who made the setting.

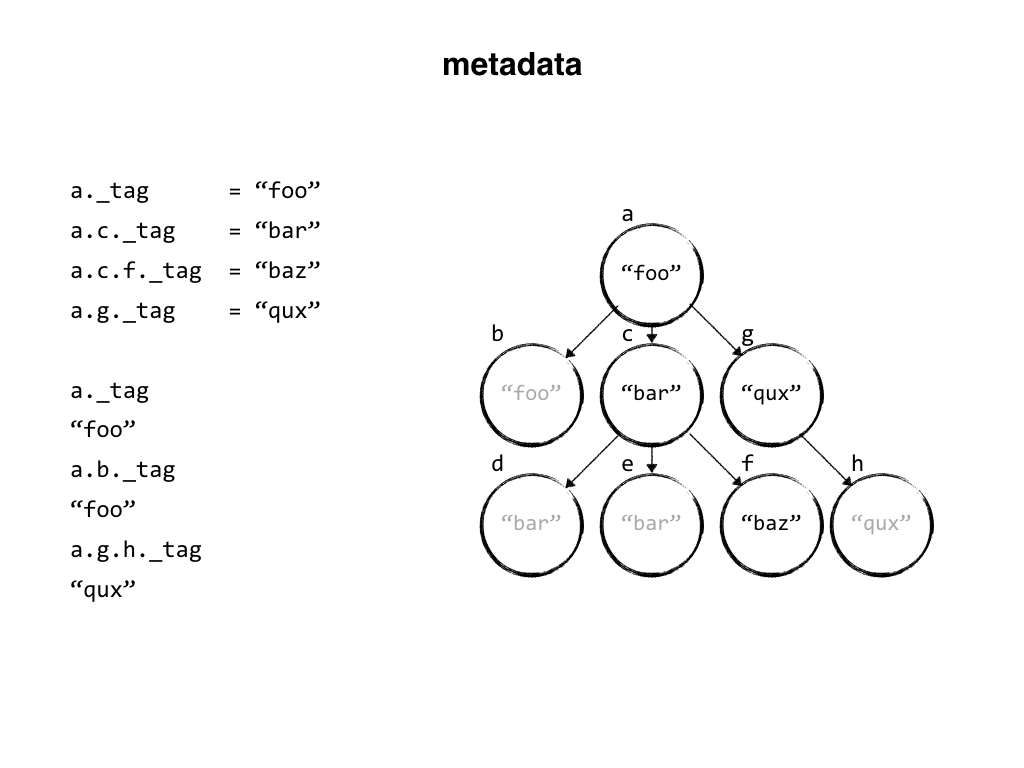

In our new system, when a developer creates a setting, they store right alongside it any information needed to find, understand, change, and validate that setting. So our system contains not just data but metadata - a title, a description, and a schema at least, but it can also include tags that identify where the data should be exposed, and access control information defining who can view and change it. The metadata tells us everything we need to know to expose the setting anywhere we'd like, with documentation that comes straight from the creator.

Our trie data structure holds metadata in each node, and when we query the configuration service we can request just data or data and metadata. Either way, as it traverses the trie to get the data, it picks up the metadata, composes it with the metadata on child nodes, and uses it to figure things out like what data types to expect and who can access the data.

We've been carving up our original monolithic code base into microservices, but we're only half way there and have a year or two to go. Our new configuration system has to support legacy code. We don't really have a choice.

I knew if we delivered a configuration system that required other teams to drop their work on microservices and rewrite legacy code, I wouldn't get the buy-in we need to make the project successful. On the other had, if we chose to only support new code and ignored legacy code, then our internal customers would be stuck with the old configuration management tools running alongside a few shiny new tools, and they would hate us for it.

We addressed the problem of supporting legacy code by using a functional data store based on two patterns, Event Stores and Command Query Responsibility Segregation.

A functional data store is a pretty broad label that means a database that doesn't let you change any data, it just lets you transform it. For comparison, we're all probably familiar with a CRUD database. It lets you Create, Read, Update, and Delete data. Functional data stores don't do updates or deletes. Instead of updates, we create a new state for an existing record. Instead of deletes, we can mark things as "gone" beginning at a certain time. Things change over time, and very often we want to know what data we had before the current data, even if the data was "deleted". Sometimes especially if the data was deleted.

Our functional data store is based on two design patterns that work really well together, Event Stores and Command Query Responsibility Segregation.

Event stores are like your checkbook register. With most databases, we overwrite a value when it changes. That'd be like keeping your checkbook balance by erasing it and writing a new one every time you spend some money or make a deposit. Uh-uh. We keep a list of every transactions going back to the first deposit we made when we opened the account. From that list we can figure out what our current balance is, as well as what our balance was at any point since we opened the account.

Command Query Responsibility Segregation is the difference between the checkbook register and the running balance for your account. When we make a deposit or draft a check, that's the command side. When we want to know our balance, we don't start at the first deposit and calculate everything since. We simply look at the running total column. That's the query side.

We built our configuration system with these two patterns, and because of that we got a design win that we needed but hadn't thought of. Our customers don't have to all upgrade default configurations at the same time.

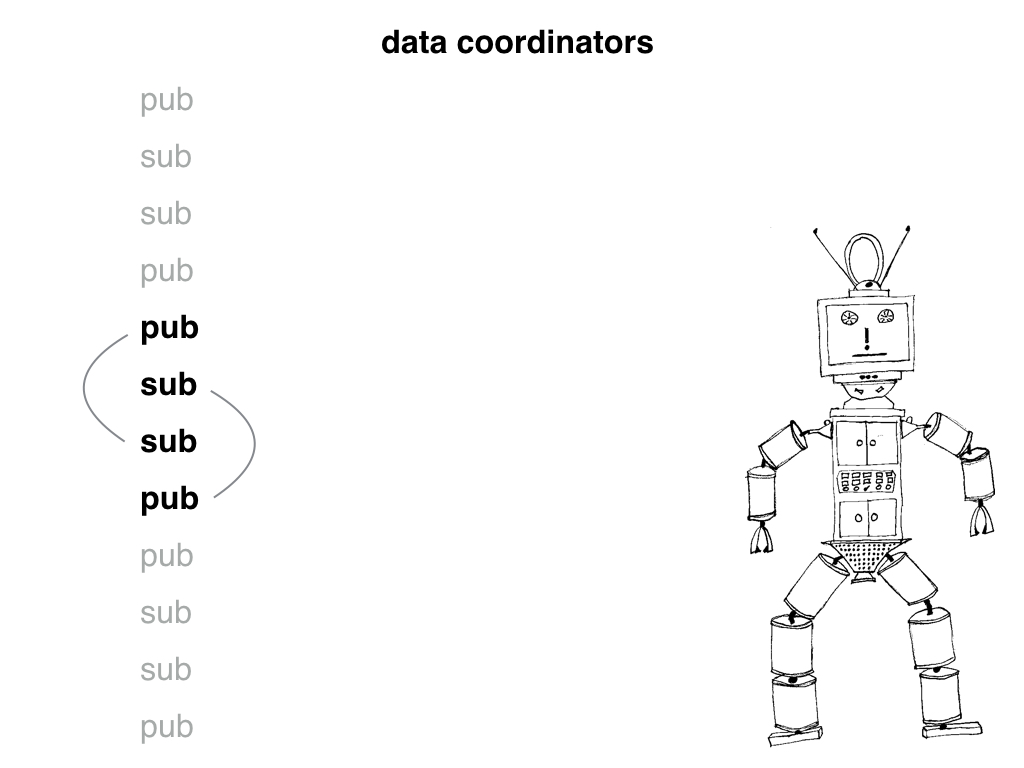

When something changes in the configuration service that also exists in Oracle, we need to update Oracle, otherwise the legacy code won't see the change. Likewise when legacy code changes something in Oracle, we need to treat that like any other configuration event and update our configuration service so that the new code can see it too. We do this by using "data coordinators".

We have two types of data coordinators. Publishers listen for changes in a data source and publish any changes to a pub sub queue. For example, our Oracle data coordinator watches the redo log, and if any of the rows it cares about are changed, it publishes the change to a channel. Likewise with the configuration service. Whenever it changes anything, it sends out a message about the change.

Subscribers listen to those channels and do something useful with the information. On the Oracle side, the data coordinator maps keys in the configuration service to rows in a table. When it gets a message about a change on the configuration service, it updates the row.

Even though it looks a little like we're trying to keep two data sources in sync, I think we aren't. The configuration service is the canonical data source. Oracle is just a place where we store a view of that data as well as an event source about changes made by a user.

Basically we built a platform that watches for data to change, and when it does it publishes a message. We made it possible to subscribe to our data, not just poll it. It's almost too good to be true. I'm rather worried it is too good to be true. If you want to explain to me why it's too good to be true, I'm available after the talk. Seriously.

Our work on this project covers configuration and configuration management end to end. We're not only building a configuration service, we're building the tools to manage it.

Our current configuration management tool is a web app that exposes all the settings for any user in one long list. We don't want that. We want our internal customers to have bunch of small tools that support their workflow. But we don't actually want to focus on builing each of those tools, so we built a tool that builds and manages all of those tools.

We want our internal customers to design their own tools, and bring them to us to build. We expect to be able to turn those tools around quickly - possibly even the same day. If we make it simple for them to work with us, and we deliver new workflows quickly, then they will be able to iterate on their own processes.

One of my goals for configuration management is that juniors should be building these tools. That'll be a good indicator that we managed complexity well. But there's more. When I started, we had no work available that juniors could do, so we couldn't hire them. If we can't hire juniors, then we can't build future seniors. We can't contribute to the growth of our community in that way. And we can't get them started off right. We're a really good company, and people are really important to us. That's why I work there.

Most of industry seems to treat functional programming as something senior developers do, and maybe even just the best senior developers. It's almost as if we don't trust someone with functional programming until they've proven they can go a decade with object oriented programming and still not murder anyone. We're teaching new programmers to live with complexity, rather than how to minimize it.

I want to help change that. Our interns and juniors learn functional programming. I teach functional programming to new developers outside the company too. We're doing a session this weekend with the London chapter of Women Who Code. Ask me about this if you're interested.

Ultimately, whether seniors or juniors build our configuration management tools isn't exactly part of the functional specification, but it's working for us. We even have a team of interns working on the first set of tools now.

There's a natural boundary between server and client software, just like there's a natural boundary between the company and the user. Unfortunately, we've spent much of the history of the internet building systems that violate that boundary.

Companies have goals, and users have different goals. I try to design systems that keep the company's interest - mostly the data and it's integrity - on the server, and the user's interest - meeting their needs online - on the client. Servers shouldn't do client things; they should apply business logic and expose the company's core competencies through a useful interface. Clients shouldn't be constrained in meeting their needs by data restrictions. I hate it when that happens. I call it the tyranny of the database.

Programs on the server should focus on the data, and client-side software should be all about the client. It's the single responsibility principal. It lets the server team focus on the company's needs, and the client team focus on the user's experience. It reduces coupling where it makes no sense to couple things. It reduces complexity.

We're doing this on our project. The configuration service offers an interface for using and managing configurations. The metadata can tell you semantic things about the settings. But the configuration service doesn't have opinions about how you manage it. That's the job of the user-side tools.

When we talked about command query responsibility segregation on the server side, we talked about events. Events are how the server handles commands. The user does something real, and the server updates its model by handling an event about what the user did. But events start with the user doing something. That something is the command.

When we put a form element on a page, we're giving the user ability to issue a command to change that value. Commands are imperative. Commands happen in user-space. Commands are part of our shared reality, what we might call "the real world".

Events are how the server tries to maintain a consistent model of the real world.

Here's another way to look at it. We can call it "sanity". In psychology we consider someone to be sane when their internal view of the world matches our shared external view of the world. Our data is sane when we maintain consistency between our user's experience of the world, and the model of the world we keep in our database.

We had to consider what happens when someone sends us a configuration value that doesn't validate. If we were just a regular database, we could reject it. But if we were just a regular database, we'd be keeping only the current state and it would break our contract with our users to send out data that lacks integrity. As an immutable and time-variant database, I think we have a responsibility to handle all events, not just the ones we like, because events happen in the real world and it's not like we can just reject reality. Even if it means our data is invalid. The decision we made was to use the metadata to flag states that are invalid. If you make a request for just the value of a key, we'll send you the most current valid state. But if you ask for the data and metadata, we'll give you the current state, even if it's invalid. Plus we can use the "invalid" flag to create a report showing which keys are broken, and ask some human being for help.

We've created a slick, functional system for building configuration management tools. And it's bone simple to use.

One of our design goals was for a single point of specification. When a developer creates a new configuration setting, we want them to tell us all about that setting. What it's called. How it's used. Who can use it. How to tell if it's valid. All of this information is stored in the metadata for the key, which means that each key can tell us everything we need to know about how to manage that key.

Metadata is the basis for our configuration management tools. Because the metadata tells us so much about the data, we can use it to automatically render a form element for changing the data. If we want to expose a setting in a configuration management screen, we simply insert one line of javascript and pass it the key. The javascript renders the form element based on the metadata.

It doesn't matter what kind of configuration management tool it is, either. It can be our internal tools, or tools we expose to our customers to administer their programs, or even tools for users to manage their profile inside the software.

Right now, the main tool for our implementation specialists and customer service team is an app that exposes all of the possible configuration settings for any customer in one long list. They designed their workflows around that list. Our new system gets away from that. We don't want their work designed around our tools. Our tools should be designed around their work, and we're going to do it so efficiently that they can iterate on their own processes.

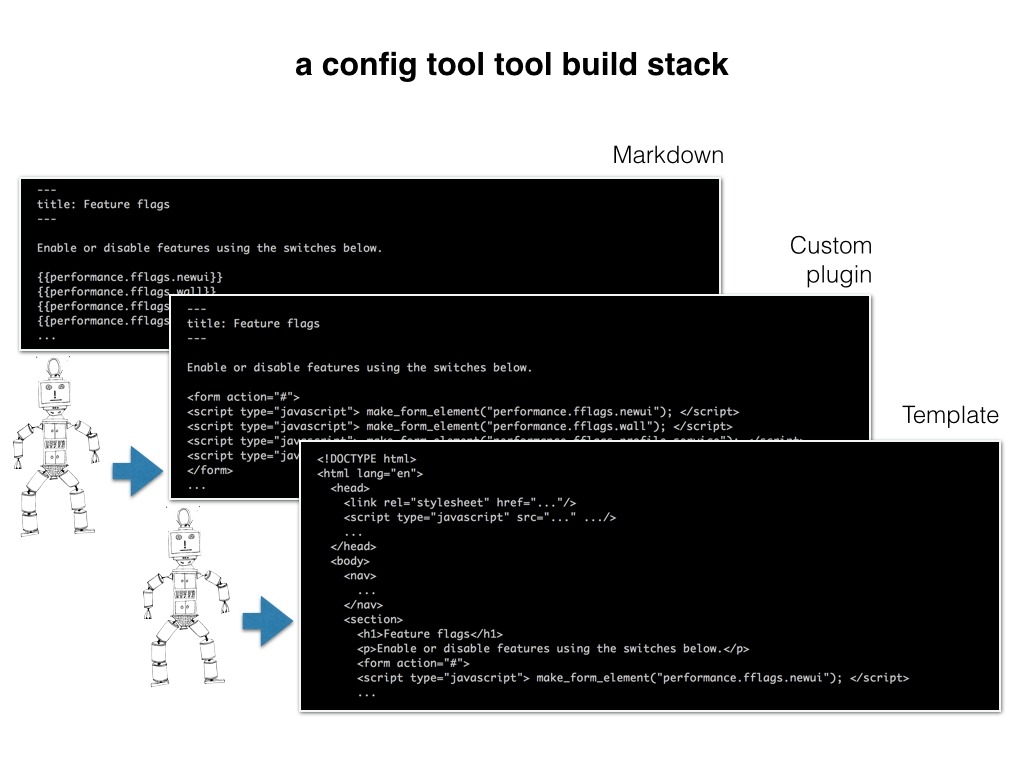

We put together a stack to build their tools. Each tool is defined by a markdown file, and where it appears in the file system indicates where it'll be located in the toolset's navigation. A static site generator called Metalsmith turns the source files into a website of custom-made configuration management tools. The site is built as a collection of static files, so deployment is just a matter of pushing them to the server.

Metalsmith is Node.js, functional, pipelined build tool. The main loop is one long filter chain operating on all the files in the project directory. We start with Markdown files. In one pass, a filter rewrites the configuration keys as javascript calls and wraps them in a form element. In the next pass, a filter converts the markdown to HTML. In another pass, a filter calculates navigation for the site. In another pass, a filter applies our layouts, including calling all the appropriate javascript libraries, stylesheets, and other assets.

The output from each filter step is the input for the next filter, until all the filters are applied and the resulting files are written to a build directory containing all of the HTML, javascript, and CSS files for the tool site.

About the time we finished our design goals and were starting to code, we were kinda thrown for a loop. Another team came to us and said they had a problem that wasn't about configuration, and they wanted to know if the new configuration service could solve it.

Our software is used world-wide. It's translated into I-don't-even-know-how-many languages, and each customer's platform is customized and translated into the languages their employees need. That means we have default translations to a bunch of different languages, each of which might be overridden by the customer.

We spent two hours together reviewing the translation service's needs, looking for the gaps between what we were already building and what they needed. We didn't find any. Our design goals fit their needs exactly.

I think that was the moment I realized that we were actually building a database.

When we started code on this project, I had one programmer available to work on it. He's great at Java but had almost no functional programming experience. We did our best, and the first release of this system - the version we have in production now - is not exactly like what I've described.

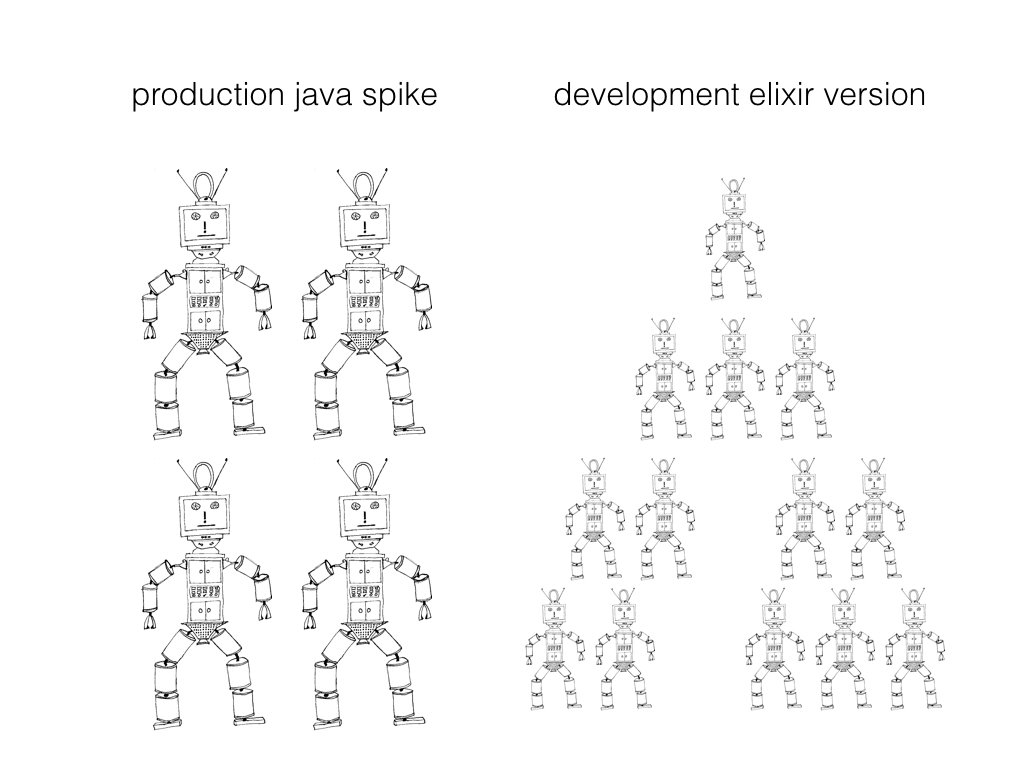

We try to work in a lean-development way, to get services into the hands of the developers who are going to use it and see what we did wrong. Our production version is written in Java 1.8 and uses one process per book rather than one actor per key. Because of this, a book is a container for a set of keys, and we can only compose data across books, and books maintain their own event stores and a single projection. It doesn't scale well - the chunks are too big.

Our development version is being written in Elixir. Here there is no difference between a book and a key - a book is just a key, so any key can be considered a book, and compositions can happen at any level. Each key is an Erlang process and maintains its own state across time, which includes metadata and either data or a link to child nodes. Each key manages its own event store as well, although this is distributed around the cluster.

In both versions, clients interact with the service using messages sent through RabbitMQ. The service also publishes data changes to the message queue so that events can be stored across multiple machines in a cluster, and coordinated with Oracle for legacy code.

That's the system, end to end, from the functional data store with immutable, time-variant data to a pipelined static site generator building the management tools. We're in the process of moving configurations onto the new service now, and we're learning from our internal customers and their patterns of use.

We do have permission to open source the code, and we will - once it's proven under heavier production load.

We haven't really done anything novel, we just combined established patterns in a way that fit our problem. We got some surprising results from that - things we wouldn't have asked for if we weren't already looking at a pattern that offered it. But believe me, once we knew we could get it, we were sure we had to have it. We also got some things we knew we needed, like significantly less complexity.

This project is fixing problems with how configuration is managed, but we haven't done anything about the consistency problems within our configurations. We've got great new tools for writing buggy configurations that are impossible to reason about. Moving forward we want to provide a way to make declarative statements about relationships between configuration values. I think implementing a dependent type system may be coming soon.

But that would be a different talk.

Thank you.