Last month I got into a discussion with a few professional members at BucketWorks[1]. Two of the participants are mechanical engineers who have a 3D prototyping company, and a third is a developer. The discussion focused on the correct way to price a software development project the mechanical engineers were expected to produce.

I happened into the conversation, but I'm afraid I may have taken it over a bit. See, I already have a system for pricing software development, so I simply shared it, in condensed form, over a period of ten or fifteen minutes. The mechanical engineers were very kind in their appreciation, which is always cool to have, and the software developer said I should present this at one of the tech meetups.

This hadn't occured to me before, but I was happy that Web414 accepted my proposal and invited me to give this presentation on pricing project work.

I write my presentations in advance, and then do my best to present what I wrote, so this post is something close to a transcript of my presentation. Actually, it's a transcript of how I meant to give the presentation, without the 'ums' and 'ahs', nervous pauses, misplaced words, and sections I undoubtedly missed due to various deficiencies in public speaking.

Check out the calculator I made for calculating the CRV Factor, which is the hard part of the formula. My slides are inline below, but check out my slide deck online too. I've been using reveal.js[2] and it's pretty sweet.

Dusty Filippini, one of the @web414[3] organizers, streamed this presentation using Google Hangouts, and sent it to YouTube. The video quality is not ideal. The presentation doesn't actually start until about 17:30 and goes for about 55 minutes plus questions and answers. About six minutes into my presentation, I have computer problems and we switch machines. But once it gets going, the sound quality is pretty decent. Watch "Managing risk and selling value" on YouTube.

Hi, I'm version2beta. Some people call me Rob. You can call me either.

My presentation is about figuring out how much to charge for your work. This is one of those talks where you get to learn from someone who really, really knows what they're talking about. I've done it wrong virtually every way you can, so I came up with a system that, so far and without fail, has told me how much I should have charged for every project I've underquoted.

It works proactively too. In fact, that is the recommended way of using this system.

I'm going to warn you right up front, there are going to be mathematics in this presentation. Real math, the kind you need a scientific calculator to do. Or a log table, if you're over the age of 50 and know how to use them.

Or you can use the special calculator I built for doing this math. It's on my website.

Before we get into the details, I'd like to tell you about my first ever paid programming gig.

slide

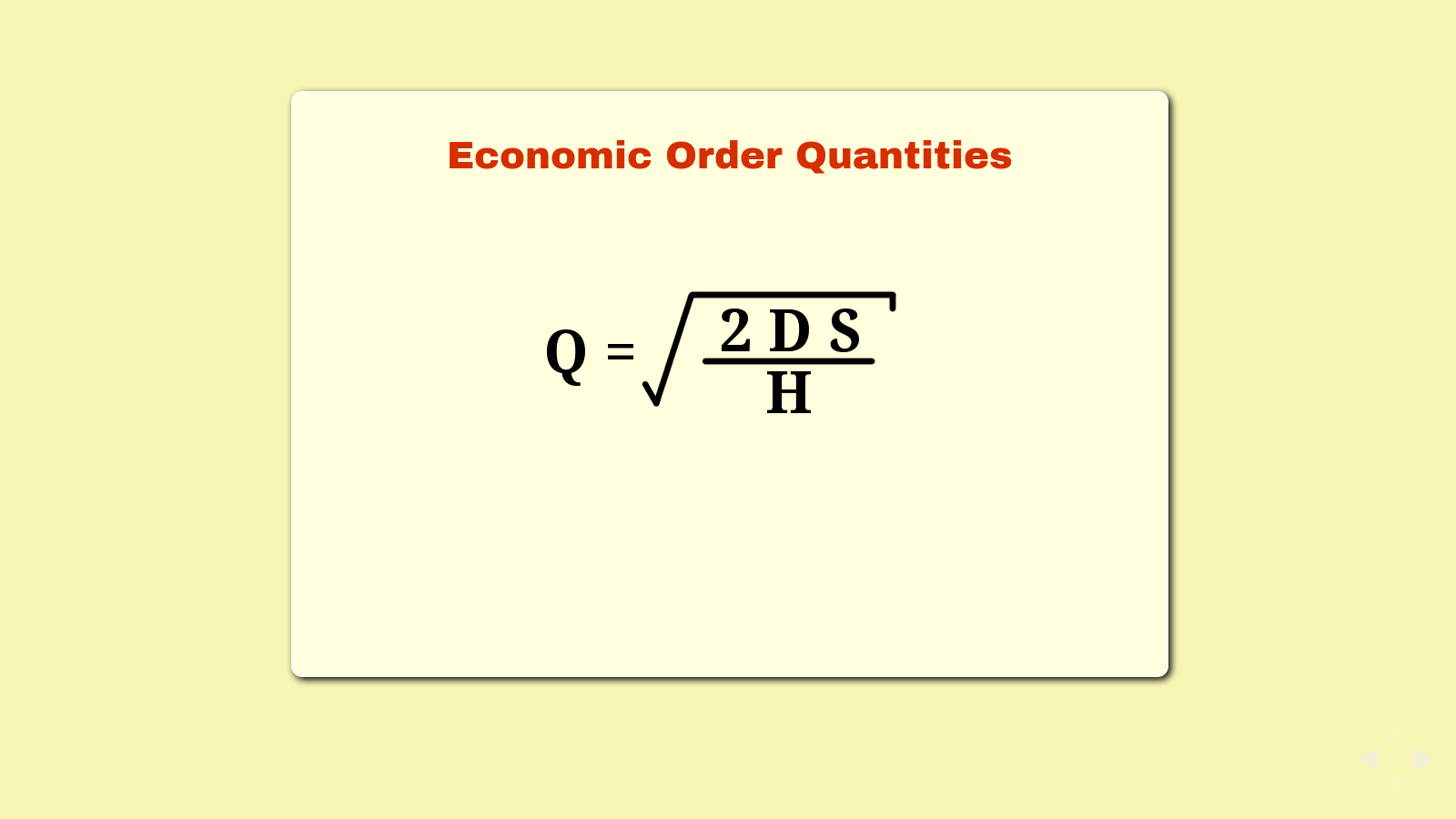

- Q is quantity

- D is annual demand

- S is fixed cost per order

- H is annual holding cost

slide

This formula is used to calculate the economic order quantity for inventory.[4]

It's been around a while. I first learned it in 1983, when I was 13 years old. I don't know if it's true or not, but at the time, I was under the impression that my father was one of the creators of this formula. He was inventory control manager for Simpson Paper Company, Eastern Division. His job was to make sure they had the right raw materials on hand, in the right quantities, for all of the plants east of the Mississippi River.

He had this formula that would help him figure out how much stuff to buy. He also had the only IBM PC at Simpson's Vicksburg, Michigan offices.

And he had a very nerdy kid. I didn't know it then, but I was going to write the student council's computer dating program and run the annual computer dating fundraiser every single year for the next four years.

The formula isn't too bad. Basically, you take the annual demand for an inventory item, multiply that by twice the cost per piece, divide that by the holding cost for one item for a year, and then take the square root. The resulting number is the ideal quantity to minimize your total ordering and holding costs for the year.

I know this isn't actually very interesting. But this formula has a square root symbol in it, so it's going to make the formulas I show you in a little while look easy. So it's important you pay attention.

The short story is that my father had me code this formula. He paid me $30 and took it to the office and that was the last I heard about it for a year.

Let's fast forward to the Superbowl, about a year later. Every year the DeYoungs came to my parents' superbowl party. Mr DeYoung worked with my father at Simpson paper. During this particular Superbowl party, Mr. DeYoung pulled me aside and congratulated me on the program I wrote for my father.

He said, "That program saved us $3 million dollars last year."

Even as a freshman in high school, I could do math pretty quick in my head. The $3 million dollars was a very significant return on investment for the $30 I was paid.

It seemed possible I had underquoted that job.

slide

Complexity

Risk

Value

slide

I have a formula for helping people figure out how much to charge for their work. It's called the CRV Model. C-R-V stands for Complexity, Risk, and Value.

I designed this model when I worked for my wife Barbara, in her web development company. Barbara spent extensive amounts of time considering how our pricing models, indeed our entire working environments, were inadequate. She deserves a lot of credit for ideas behind the model, and the conversations inspiring it. She was invaluable in developing and testing this model.

I wish I could say it was a great success, but some credit for the model is also due our largest and most risky customer, whose $68,000 default not only demonstrated the need for this model, but also contributed to the downfall of my wife's company.

All of my experience using this model has been focused on web development and programming, but it should be useful for modeling any kind of project work. What matters to this formula is that the project is at least loosely specified in advance, and you're trying to put a fixed price on it.

slide

- BYO Business Acumen.

- Damn it Jim, it's a model, not a doctor for your business.

- When you're pointing fingers, make sure you're looking in the mirror. Kthanxbai.

slide

I have some caveats for you:

- You're going to need some business instinct to use this model.

- In fact, the more business acumen you have, the better this model will work for you.

- If you have a good sense of business, you probably don't need this model.

- If you don't have a good business sense, this model will help you develop one.

- This is not a silver bullet. It's a model. It helps you understand the world a little better.

- At the end of the day you still need to take credit for your own success. No need to call me up and say thank you.

- Same goes for your failures, by the way.

slide

Pro-tip: Ignore everything I'm about to tell you and do Agile development instead.

slide

It's also important to note that there are better systems. For example, don't do fixed price quotes.

I'm a fan of Agile methodologies.[5] I strongly recommend you ditch fixed price quoting and pursue Agile development and project management. I promise you, properly done, it works better. All you need is a lot of trust, excellent communication skills between you and your client, and the knowledge and experience to do Agile properly.

slide

- Working for the man.

- Selling your life by the hour.

- Client wants a fixed price.

- Client wants to go out of scope.

- It can be hard to get paid for out of scope work.

slide

Let's talk about why we're here. What is the problem we're trying to solve. I see it as three-fold.

First. It's very important that you hire the right clients. And in case you get a bad client, it's important to know when to fire them.

Second. Even good clients sometimes suck. They want a fixed price bid. Then they want to go out of scope. Then they want to blame you that they went out of scope, that you should have thought of that. Then they don't want to pay for going out of scope. Then if they do pay you for going out of scope, maybe they resent it.

Third. It's come to my attention that I have a limited number of hours in my life. I know that sometimes it feels infinite, but I've consulted with some pretty good doctors, and they assure me I have an expiration date. It's true.

This may also be true for you. You should consult with your doctor. If by any chance your doctor confirms this, then you, like me, are in a position to decide at what hourly rate we're willing to sell our limited lives. Or if we want to sell our lives by the hour at all.

I think we can distill these problems down to a list of goals for a pricing model.

Pursue the right work. Avoid the wrong work. Mitigate risk. Charge according to value.

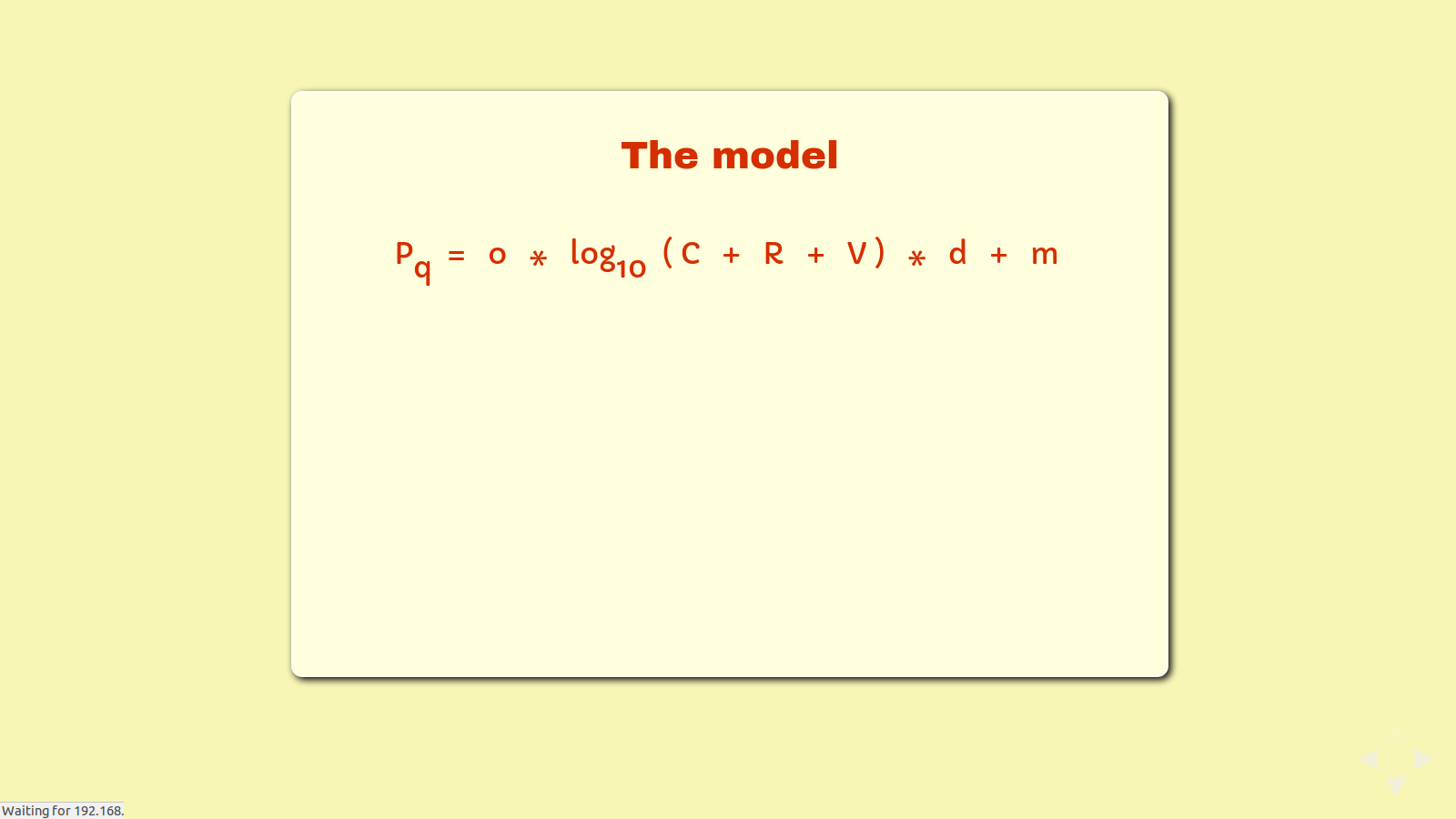

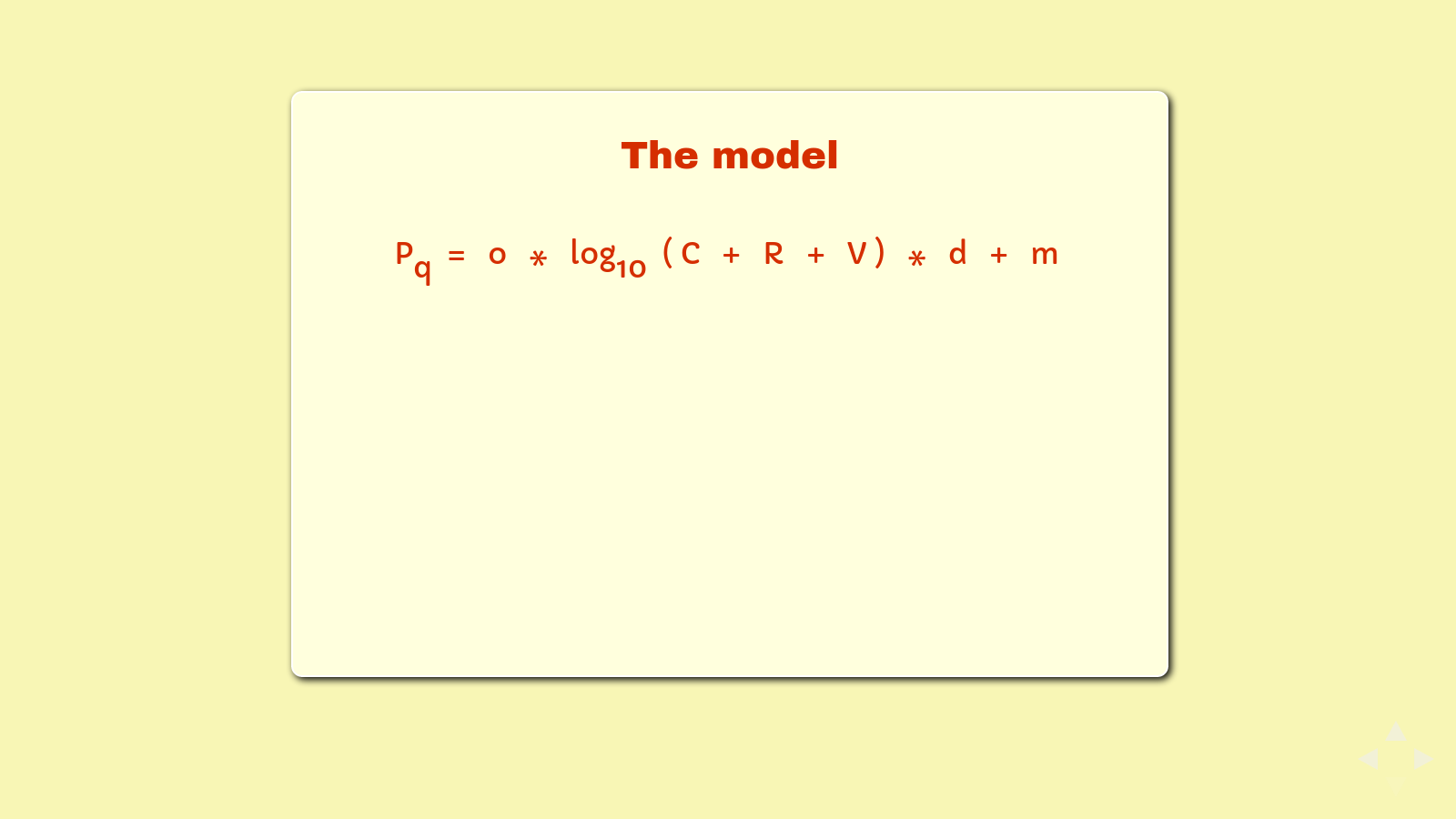

So here it is. Scary. It even has a logarithm[6] thingamajig in it.

Let's walk through it, one parameter at a time.

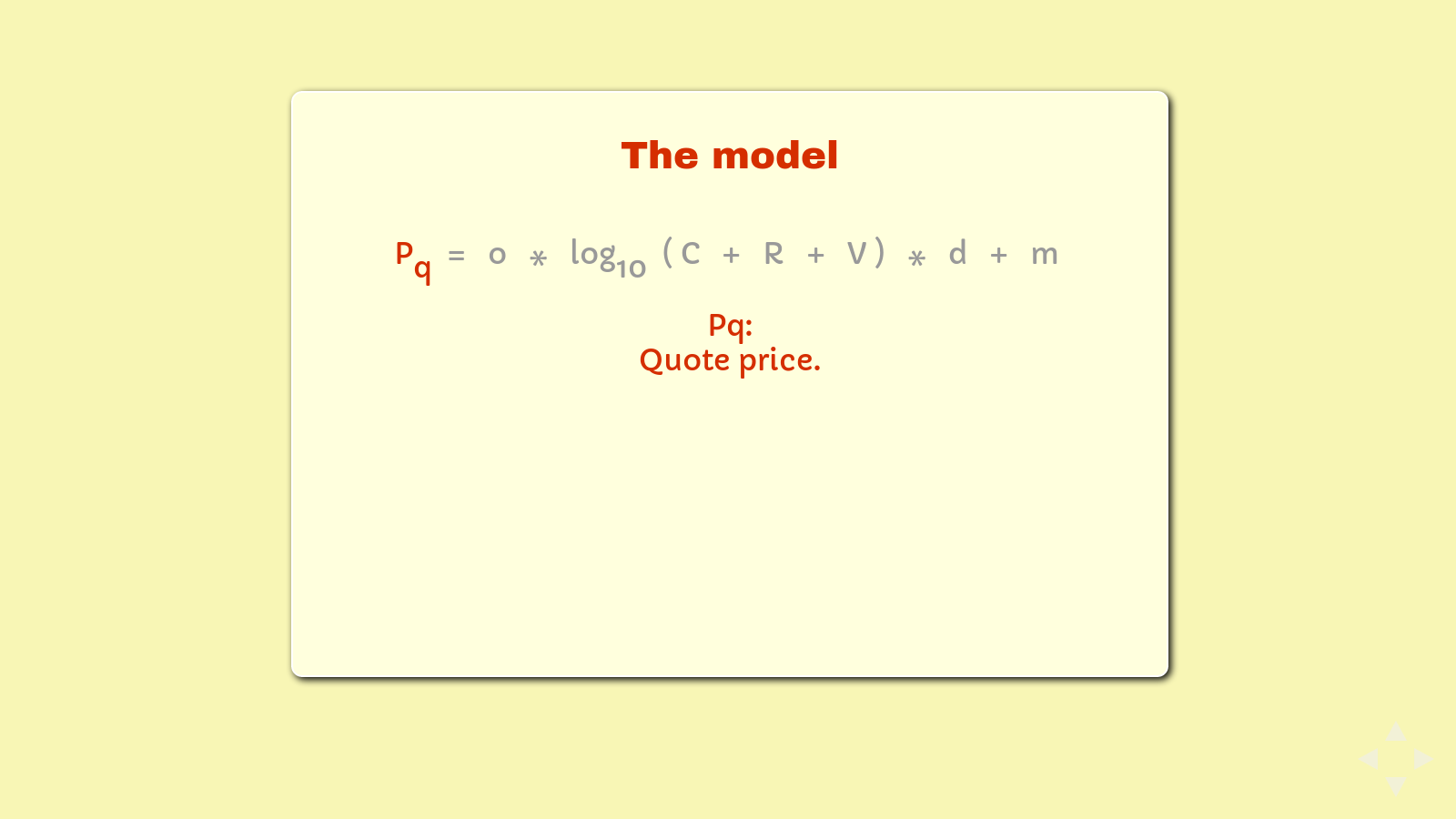

On the left side, we have the quoted price. This will be the product of our calculation, and the price the model suggests for your project.

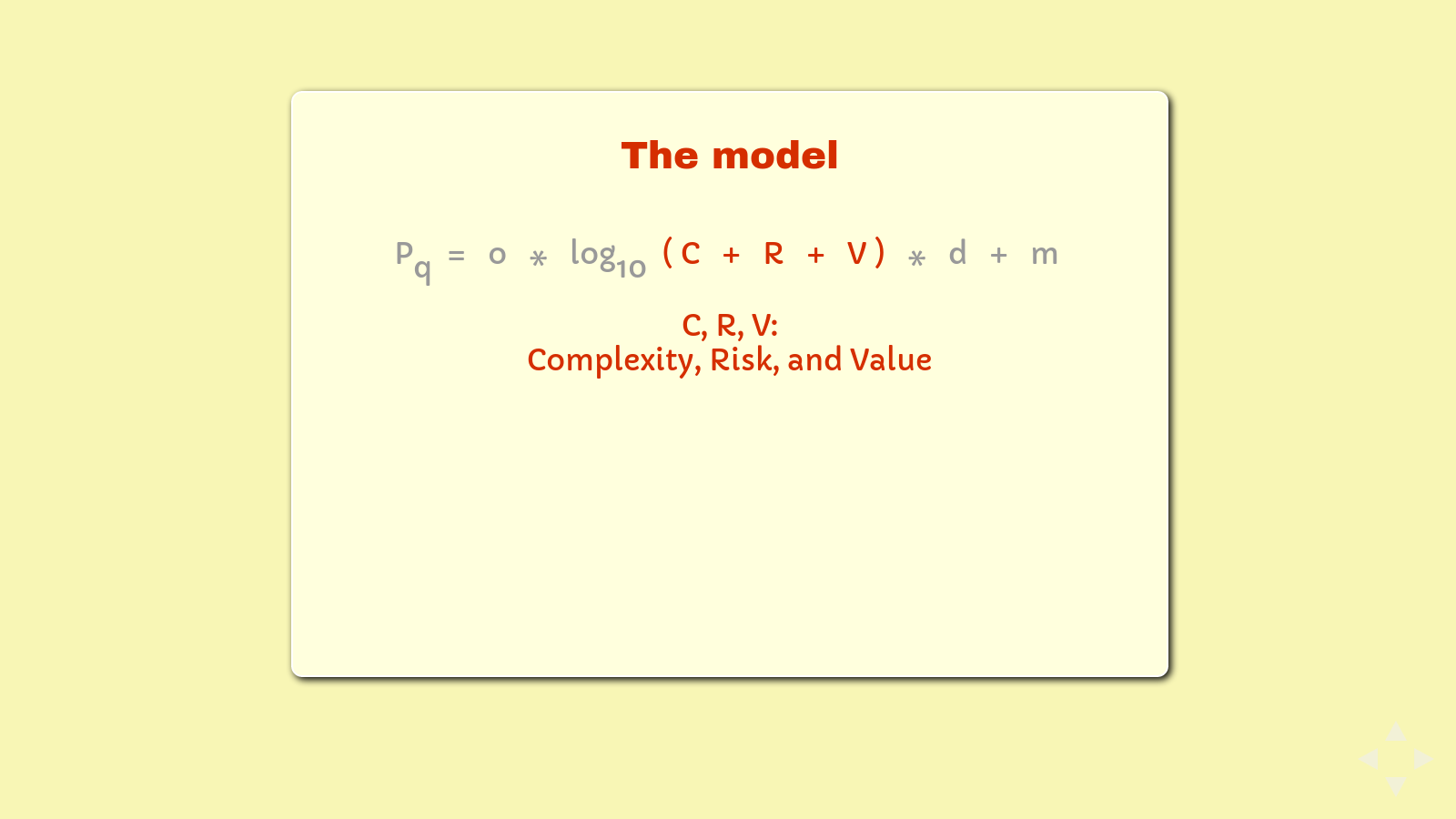

C, R, and V stand for Complexity, Risk, and Value. We are going to look at these terms in detail.

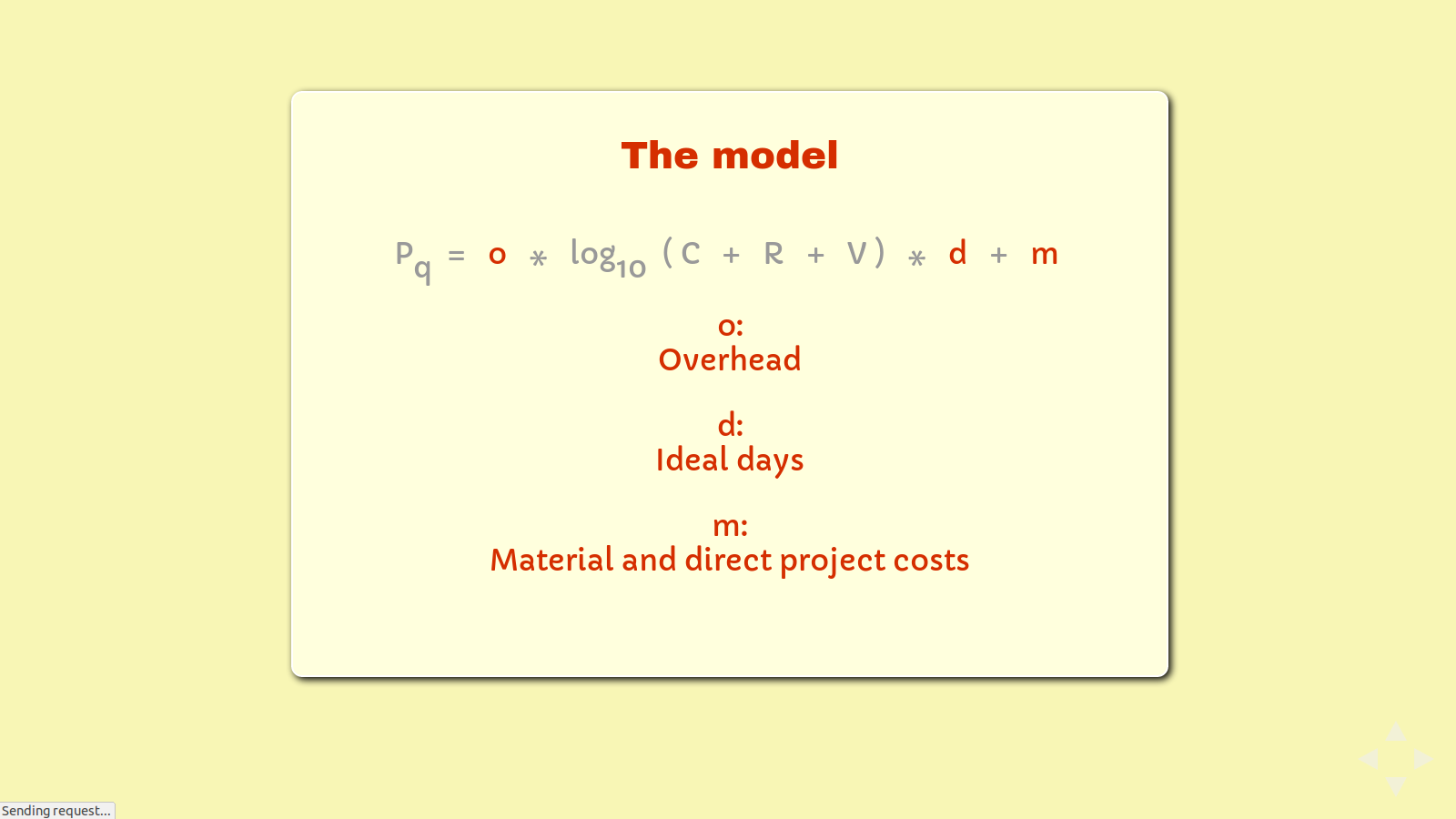

I'm going to call these three little factors your constants. Overhead, days, and materials.

The little 'o' is your overhead. This is just enough to cover you basic costs. This will vary a lot based on how big your business is, whether you subcontract, etc. We'll discuss this in more detail.

The little 'd' is your time estimate in days. It doesn't need to be exact. We'll cover this more too.

The little 'm' are your material and other project costs. If you are going to have project-based expenses other than time, put it in here. If you mark up your direct costs, put the marked up amount in here.

So that's the formula. It's not as scary as it may have seemed at first.

Add some numbers together. Those are our factors for Complexity, Risk, and Value.

Apply a logarithm. This is the exponent you'd put on the number 10 to get this number. It's also the log10 key on your scientific calculator app.

Multiple by a couple other numbers. That gets us our overhead for the job and how many days of overhead we need to cover.

Add in the remainder. That's any direct or material costs.

You've got your price. Let's look at the specifics.

slide

o : Overhead costs per work day

slide

While Complexity, Risk, and Value are the real focus of this formula, let's get our constants out of the way first. Let's start with overhead.

Just in case you're wondering, our formula is managerial accounting, not traditional balance-sheet type accounting. For example in cost accounting, our labor is divided into time-based units of measure and we put a cost on each full unit and use that for our basis. That's the system we're getting away from.

Managerial or analytical accounting uses a variety of accounting-type metrics to answer specific questions, usually questions about the future. That's what we're doing. We're using a handful of metrics to ask questions about the future cost of doing a project.

One of the questions we need to answer is, "How much of my overhead costs do I need to assign to this project?" This is the little 'o' in our formula. Overhead.

slide

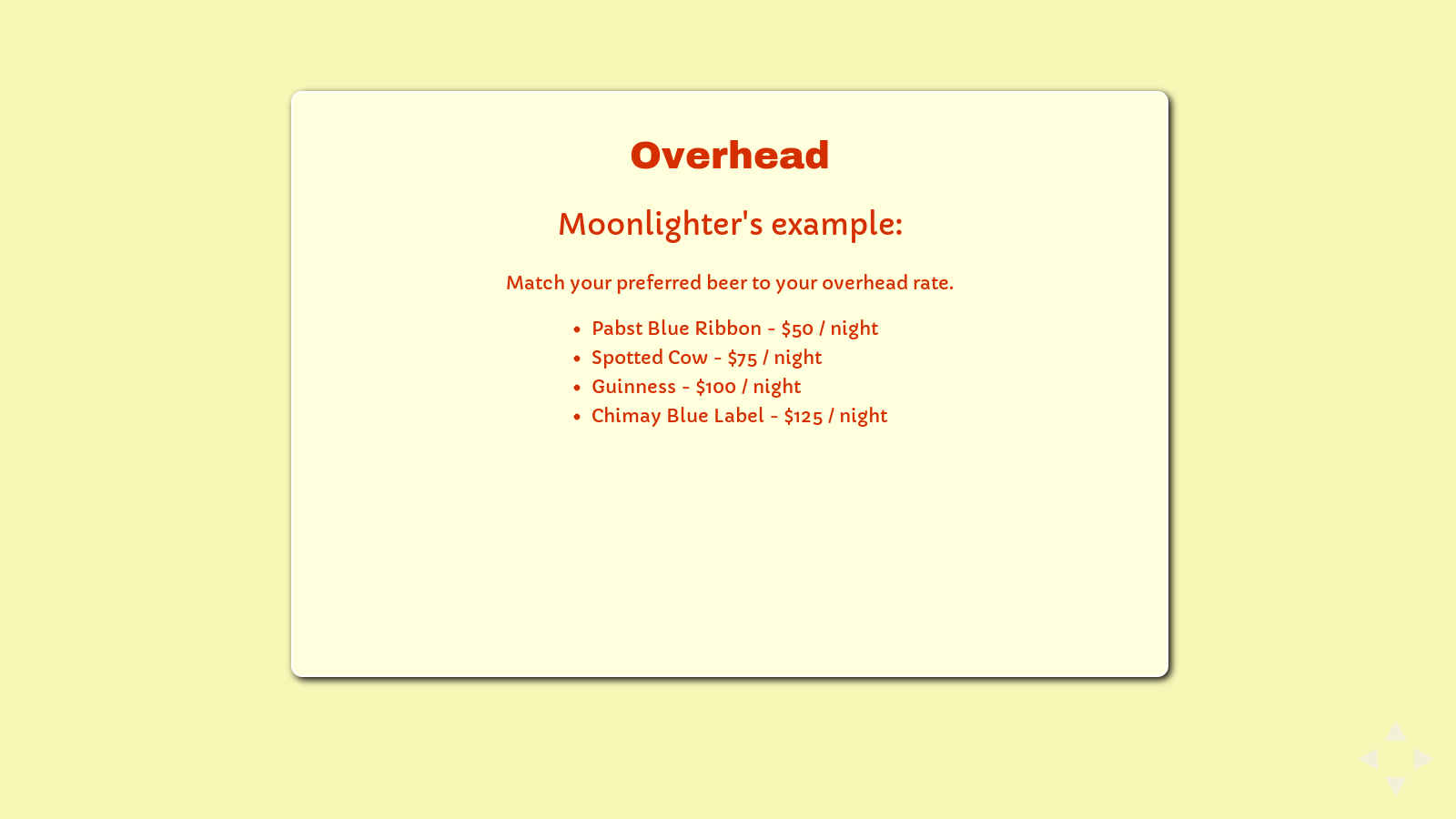

Match your preferred beer to your overhead.

- Pabst Blue Ribbon - $50 / night

- Spotted Cow - $75 / night

- Guinness - $100 / night

- Chimay Blue Label - $125 / night

slide

Moonlighters, raise your hand. Now keep your hand up if "overhead costs" and "beer money" are roughly the same for you. I've been there. I still do some work that way. I admit, this example is a little bit tongue-in-cheek. If I were serious, I'd have used whiskey in the example

I would like to remind you that there are a lot of people trying to feed families doing the same work. Be careful about setting this value too low. I suggest you use the freelance example instead, and think about pricing your work as if you are doing it full time.

slide

- I want to take home about $30,000 a year.

- Taxes are about $7,500 a year.

- Health insurance costs $6,000 a year.

- I spend $1,800 a year on sales and marketing.

- I spend $2,000 a year on new computers.

- I spend $3,000 a year improving my skills.

- I expect to do billable work three days a week.

Overhead per work day = ( 30,000 + 7,500 + 6,000 + 3,000 + 2,000 + 1,800) / 150

Overhead per work day = $415

slide

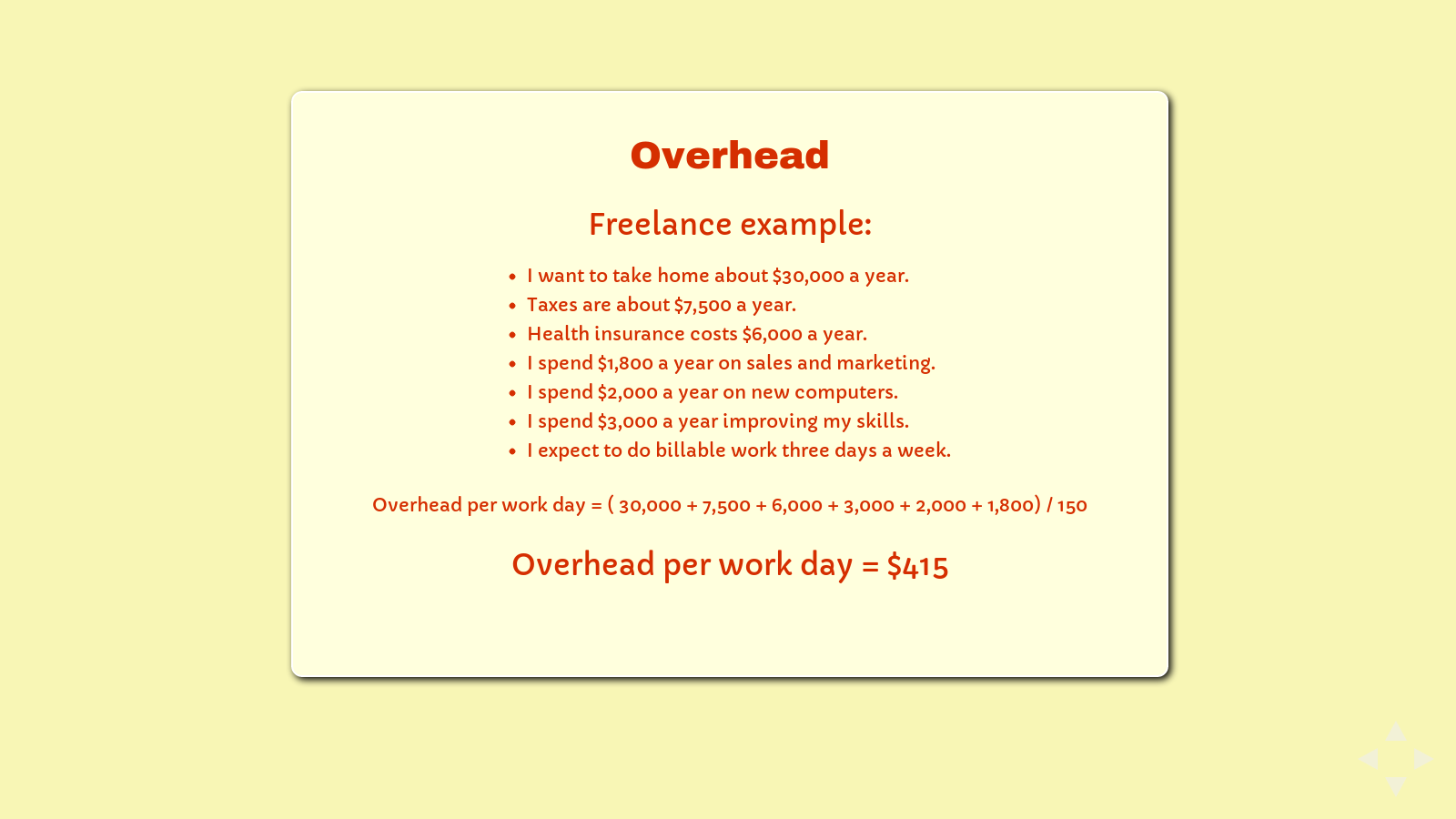

Let's walk through an example calculating overhead for a single person freelancing. No employees. No employer.

If I am this freelancer, this is what I need to know:

What's the minimum I could make in a year and still be happy freelancing? Or moonlighting?

I need to increase that number by 25% to cover taxes and self employment taxes.

If I plan to do this full time, I'll add in the cost of my health insurance. If you have health insurance that's paid for by someone else, for instance your partner's employer, add in half the value of their insurance benefit. If you don't have health insurance, add at least $6,000.

Now add in any business expenses I expect to have for the year. Sales and marketing, professional development, equipment costs, insurance, business rent, professional memberships, etc.

Then I figure out about how many days I actually expect do production work, and I divide by this number. If you plan to do this full time, figure on something between 120 and 180, depending on how much time you need to spend selling.

In the example above, I arrive at a "per project day" overhead cost of $415 for this hypothetical freelancer working something that looks very much like full time on a very modest income of only $30,000 a year take home.

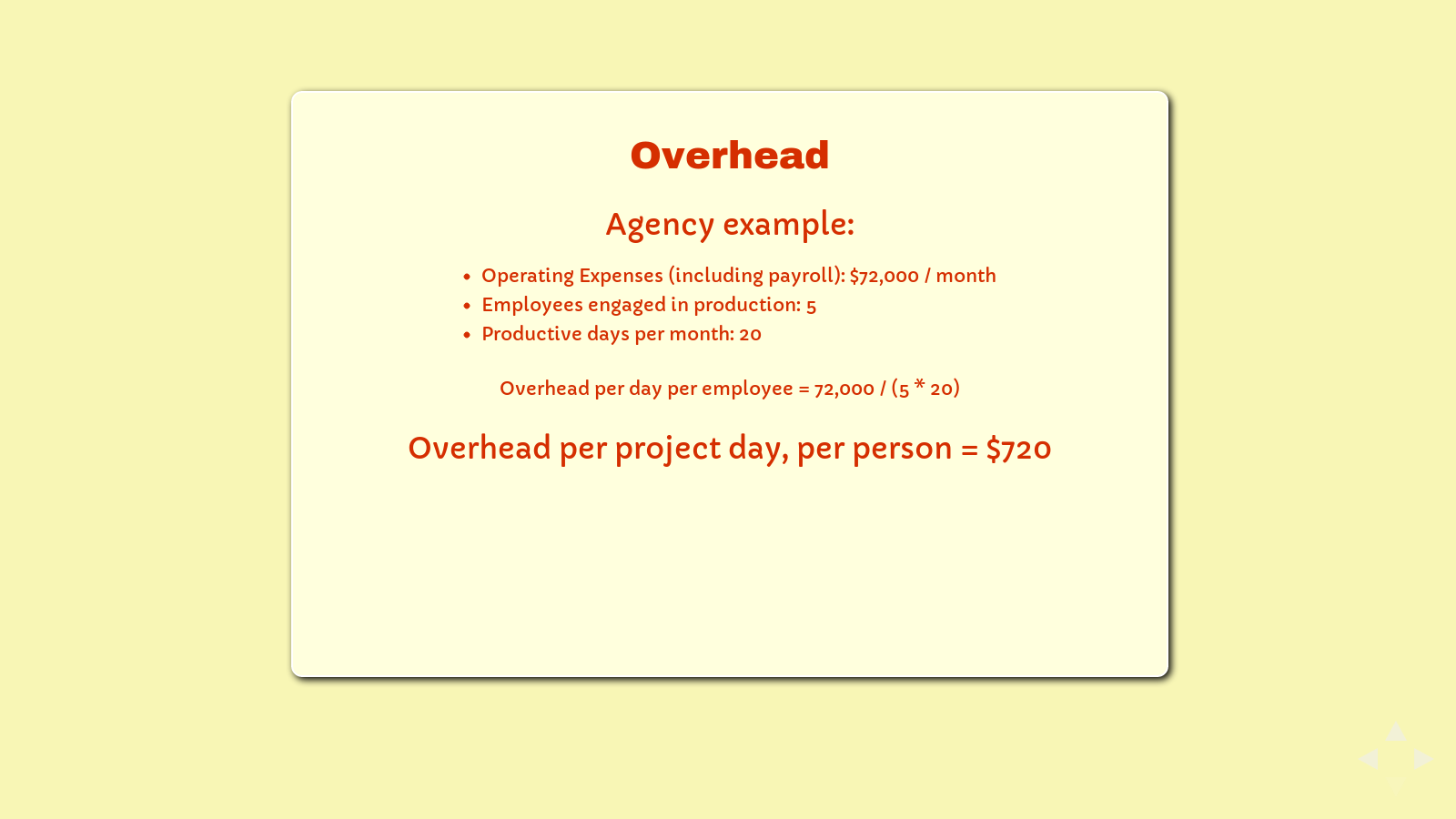

slide

- Operating Expenses (including payroll): $72,000 / month

- Employees engaged in production: 5

- Productive days per month: 20

Overhead per day per employee = 72,000 / (5 * 20)

Overhead per project day = $720

slide

Here's another example, this one for a small-ish agency.

For agencies, I think the numbers are pretty simple to follow. Add up all your expenses, including payroll, even for billable resources. Divide it across the number of people doing billable work.

Again, we're not doing cost accounting.[7] If you're interested, this formula is inspired a bit by Throughput Accounting,[8] but the important thing to remember is that we don't want to slip into the habit of thinking in terms of hours of labor.

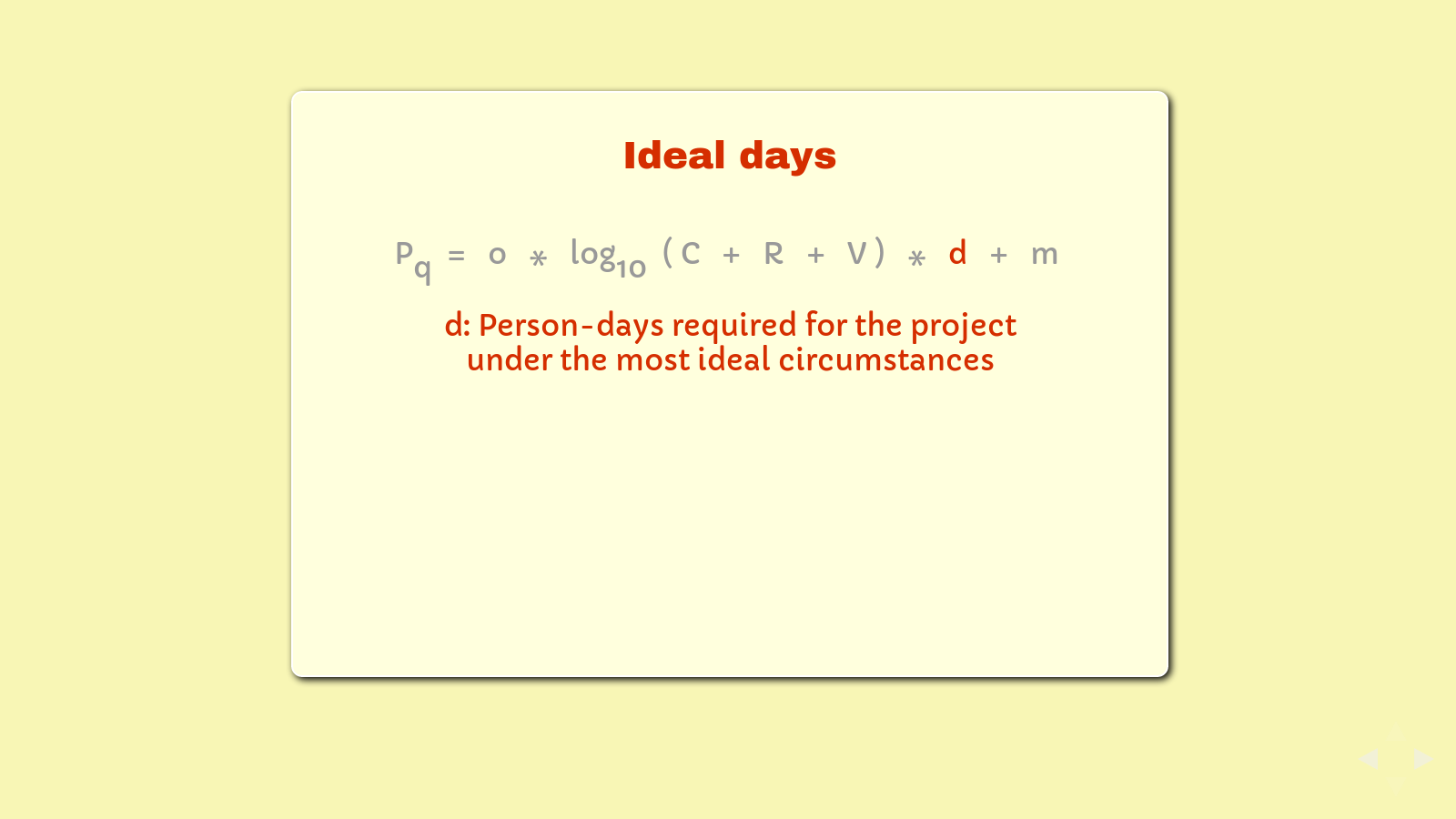

slide

d : Person-days required for the project under the most ideal circumstances

slide

We are not going to try to figure out how many hours or days or weeks a job will actually take. However, we are going to consider how much time it would take under the most ideal circumstances.

I think this is a real selling point for this model. We'll talk about this more in a few minutes, but when we're using this model we get to think in terms of the best possible circumstance. This is a huge advantage because it's easiest for us to accurately predict what's going to happen if everything goes perfectly, rather than if all hell breaks loose.

So at this point, we can say sayonara to contingencies. We can ignore plans B and C. We can put in the number that only happens when the stars are perfectly aligned.

Just make sure that "days" means the same thing here that it meant when you were figuring your overhead per day. For agencies, this is the number of person-days for production employees that you would assign to the project - under the most ideal circumstances. For freelancers, this is the number of work days you think the project would take you - under the most ideal circumstances. For moonlighters, this is probably the number of evenings or weekends you think you'll need to work on the job. Under the most ideal circumstances.

Again, the important thing to remember here is to be a paragon of optimism. Plan on rainbows and unicorns.

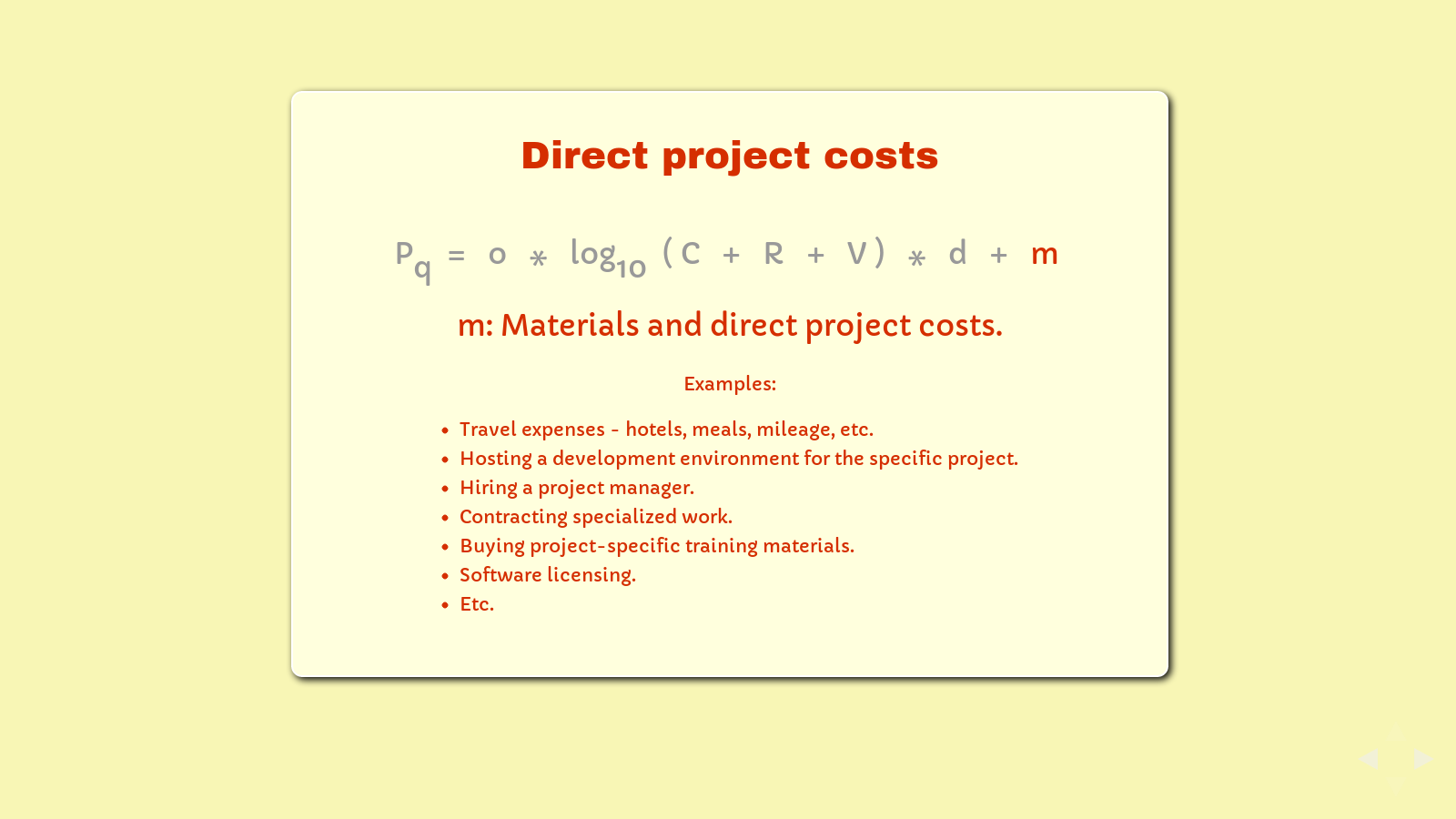

slide

Examples of materials and direct project costs:

- Travel expenses - hotels, meals, mileage, etc.

- Hosting a development environment for the specific project

- Hiring a project manager

- Contracting specialized work

- Buying project-specific training materials

- Software licensing

- Etc.

slide

Little 'm' is easy. It's any direct costs associated with the project, that apply just to this project.

For example, if you need to hire a specialist, put his or her costs in here.

Actually, I've done this a bunch of times. On one project, I was programming the controls for an automated heat treating line. This particular system used huge vats of molten salt for heat treating the parts. The system was basically robot arm on a 120 foot long track that picks up baskets of parts, each basket weighing about 300 pounds, and moves them through the heat treating process. Each basket got its own recipe, based on the kinds of parts inside. So a given basket might go in the hottest vat for 30 seconds, then quench for 30 seconds, then do something else.

Believe it or not, that was the easy part.

The hard part of this project was adding the ability for the heat treating company to tell the computer what parts were coming up, so that the computer could decide when each basket should be loaded in order to maximize throughput. For that I hired an outside consultant, a guy named Kim Duk-Won.

Kim is great. Before I went to visit Korea, he taught me to read and speak enough Hangeul so that I could get around town, order food, and find a bathroom. When he did his Masters thesis, I helped him with the programming. When I hired him for this project, he had completed his Ph.D. in Operations Research, done a few years optimizing delivery schedules for FedEx, and was teaching at the University of Tennessee at Oak Ridge.

On this particular project, Kim gave me a fixed price quote. You know, because I'm that kind of customer.

Paying Kim to work on that project was a direct project cost.

slide

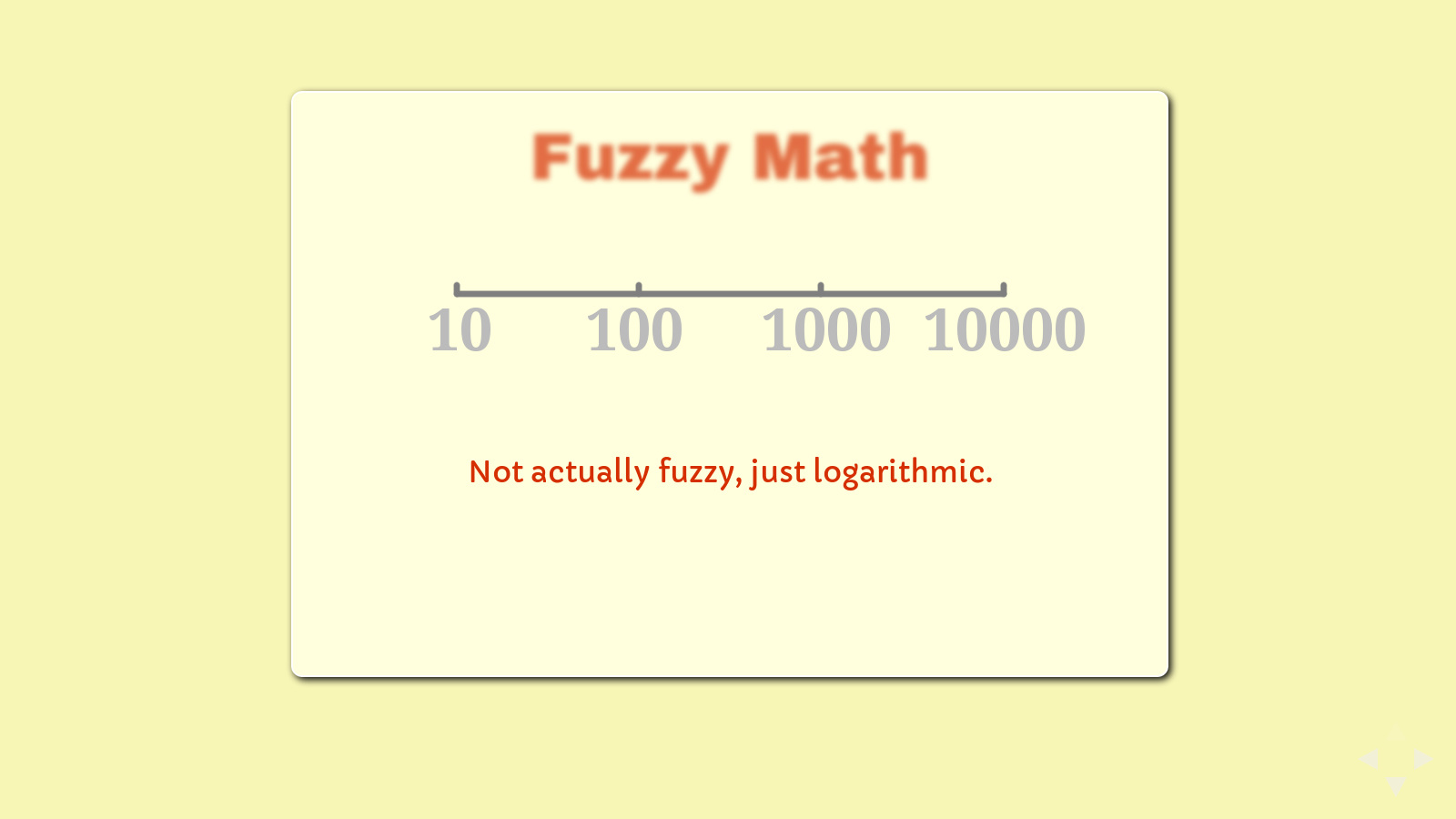

Fuzzy Math

Not actually fuzzy, just logarithmic.

slide

We're going to estimate Complexity, Risk, and Value with some pretty fuzzy numbers.

This isn't an exact science. I can't tell you that the complexity on a given project is exactly 6,423.5.

We really only know how complex something is, if it's not complex at all. We can more accurately predict risk when there's very little. And as well all know, value ranges from nothing, to a lot, to priceless, right?

When I make scales for Complexity, Risk, and Value, I want to have a lot of room to move around, and I want the scales to be more accurate on the lower end than on the upper end. I can't really use "infinity" as a value, but it'd be nice to be able to say "A whole damn lot."

So the scale we're using goes like this: Pick a number between ten and ten thousand. If any of the factors start really ramping up, use big numbers. That's what the "log10" in the formula does for us. If you really have a project that is so risky, or so complex, or so valuable that you feel like you need really big numbers to describe it, use them.

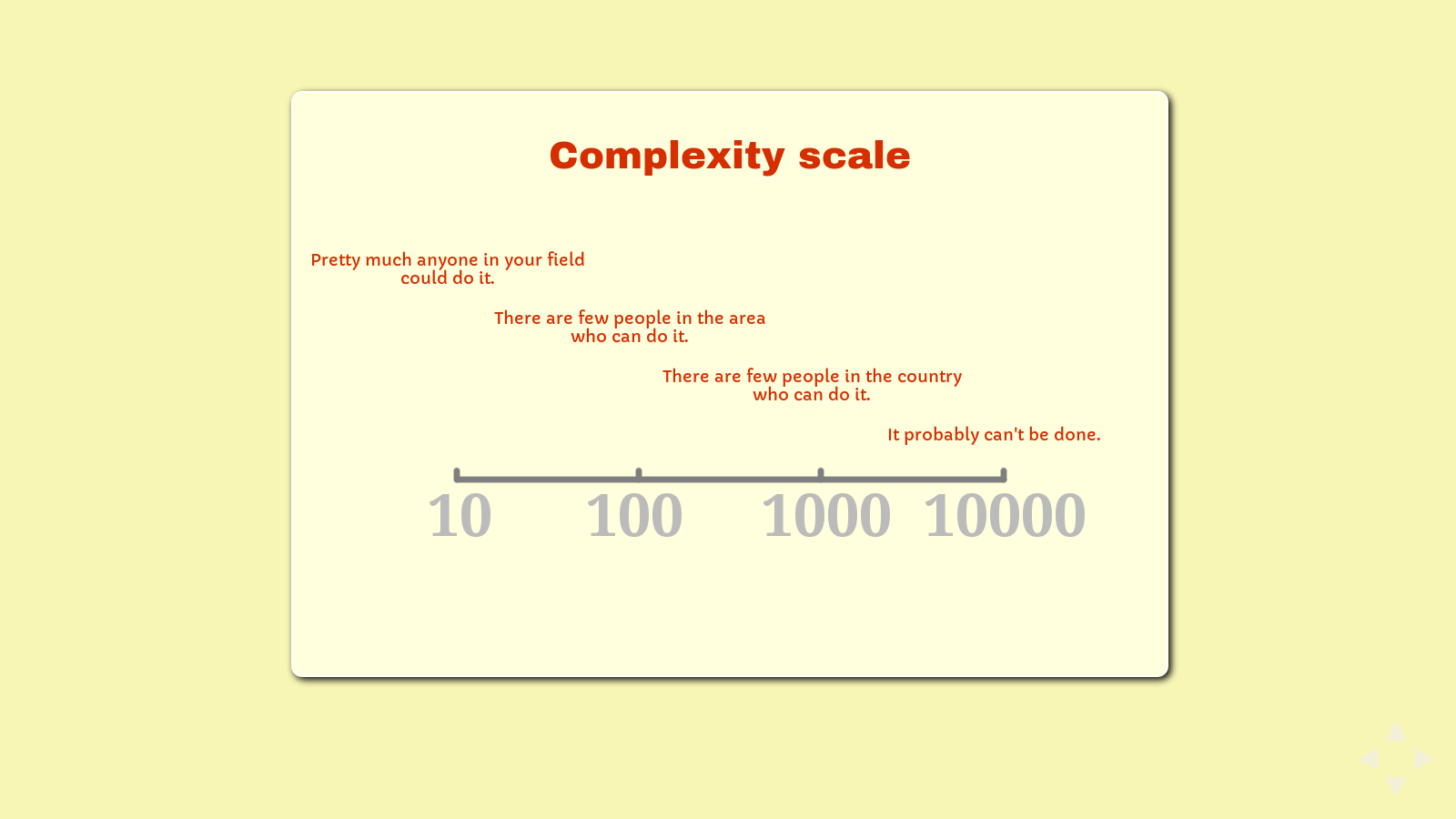

slide

- 10 - Anyone could do it.

- 100 - There are only a few people in the area who can do it.

- 1000 - There are only a few people in the country who could do it.

- 10000 - It probably can't be done.

slide

I think of complexity in terms of who can do the work. Actually, I tend to think of complexity in terms of how far you'd have to go to find someone else who can do the job. In that way, it's kind of like "competition".

You could actually use distance to the next nearest person or agency who can do this job as your complexity number. If bunches of people in this room could do it, let's say 10 since I really never use factors lower than 10. If you'd have to go to Chicago for another place that could handle it, let's say 120. New York, about a thousand miles. A univerity in Tokyo? 10,000.

My friend Kim Duk-Won is an example, right? I needed a highly-specialized algorithm that he was uniquely suited to provide. Given that the competition for that position is very limited, he can charge more for his time. It's simple supply and demand.

Here's an even better example. I first heard this example from my grandfather, who was an engineer.

There's this guy Gus who retires from his position as lead maintenance person at the local factory. He's put in his time, he's ready to be done working and focus on his fishing.

One day shortly after Gus retires, an absolutely critical machine fails. It's making a horrible noise. Nobody in maintenance knows what to do with it, so they tell the plant manager he's gotta get Gus to come back and fix it.

Gus isn't very happy about this, but he agrees to come look. He walks around the machine. He listens to it. And then he pulls a piece of chalk from his pocket and puts an 'X' on one part. 'Replace that,' he says.

The plant manager is thrilled until he sees Gus' invoice for $50,000. The plant manager tells Gus to submit an itemized invoice.

Gus sends a new invoice came with with two line items. The first line item was "One chalk mark: $1." The second line item was "Knowing where to put it: $49,999."

slide

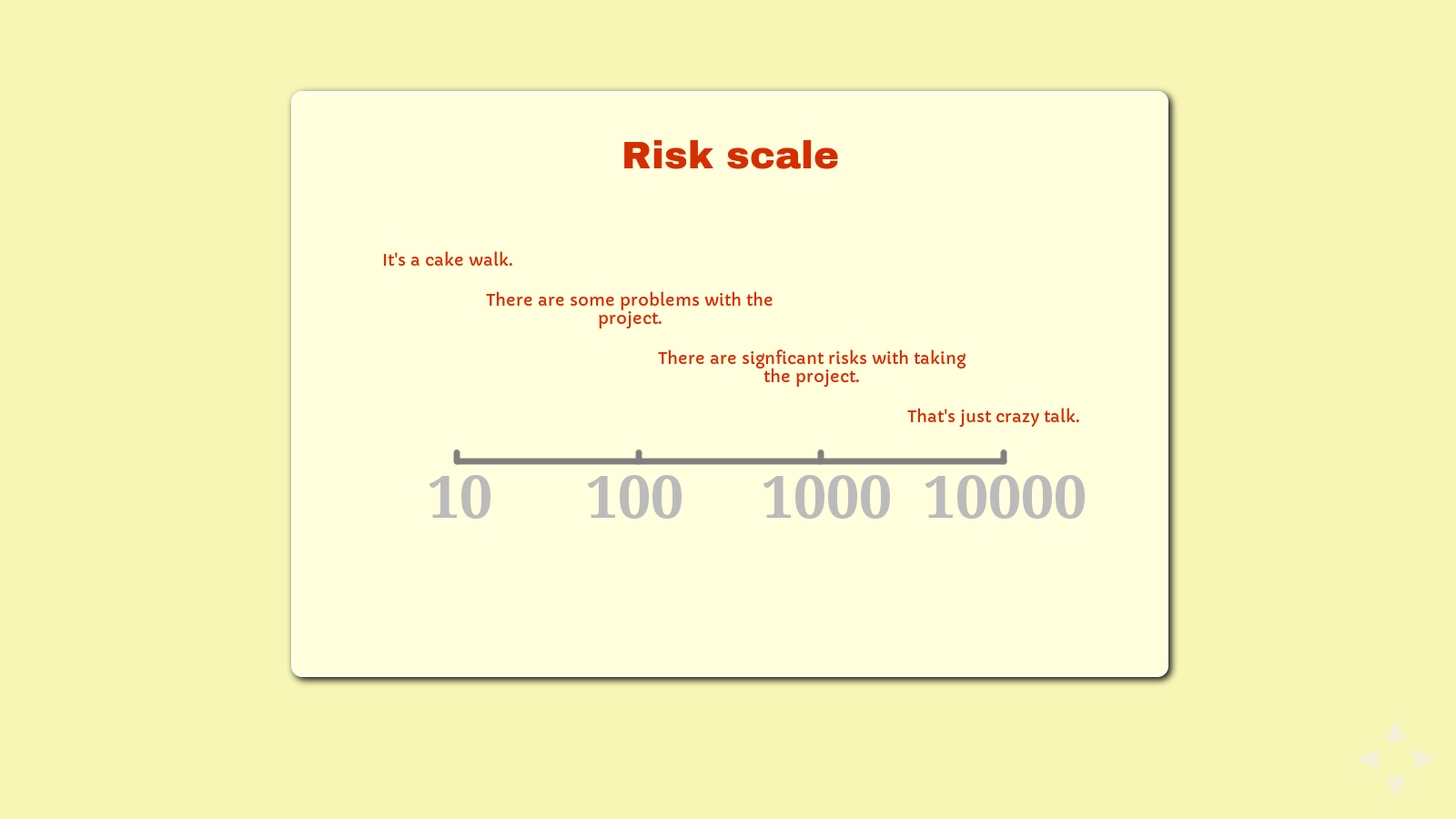

- 10 - It's a cake walk.

- 100 - There are some problems with taking the job.

- 1000 - There are significant risks associated with this project.

- 10000 - That's just crazy talk.

slide

I remember the first time it occured to me that I could change the price of a job based on how little or how much the client actually knows about the project. This happened way later than it should have. I had my hourly rate, and it was my hourly rate. Maybe I'd add in a few extra hours to compensate for some unknown. But I could have saved a lot of money and salvaged at least one failed project if I'd only realized sooner that I should always charge more for projects that have more red flags.

Let's talk about risk.

First, I want to say risk isn't for everybody. At the low end of the scale, we have "the cake walk." The job is well defined. The customer knows what they're doing when it comes to executing a project like this. They pay quickly and fairly. Maybe they're even an agency like C2[9] that specializes in contract talent.

This is good, steady, low-risk work. It's nice to have this kind of work. Many of us would do well to focus on this kind of work.

Or maybe you can tolerate a little more risk, so we slide up the scale a little bit.

"There are some problems with taking the job." Here we start to see some red flags, and we need to take them into consideration.

The specification is weak. The client seems uncertain of what they want. They don't respond well to suggestions. Their ideas seem overly fluid. That's a nice way of saying they are a high risk for scope creep.

The project has weak prospects. The project doesn't have a good cost-benefit ratio. It's unlikely to bring value to the client.

The customer seems overly cost-conscious. They may not have the funds required to manage the project well on their side.

The client talks about the previous contractors they had to fire.

Sometimes the risk isn't with the client. Let's say you're not well established yet. Maybe you don't have the skills you'd need to feel confident completing the job. Or taking on this project precludes your ability to take on other work or care for your regular clients. These are all risks too.

"There are significant risks associated with the project." Now we're getting into some serious red-flaggage.

Maybe the project has no specification, and the client doesn't want to do a discovery phase.

Maybe the client's expectation for delivery, price, and / or quality are unreasonable.

Maybe the client seems to be hitting on you.

Maybe you have little confidence in the client's ability to fulfill their part of the contract. You know, like paying you.

Maybe you don't have confidence in your ability to finish the project. It may be too big, too hard, to many moving parts.

"That's just crazy talk." Projects at this level of risk are the ones we walk away from. These are the projects with abusive clients, or projects we have no expectation will ever finish successfully.

But sometimes the client is throwing money at you in spite of the difficulties, and maybe you are pretty tolerant of risk. You might even specialize in difficult clients with deep pockets. There's money in that.

When you're quoting a project, always first try to drive risk down. Build in a discovery phase and price out the full project after there's an adequate scope. Spend extra time establishing reasonable expectations with the customer, in both directions. Discuss your concerns about their ability to manage the project, and how they may benefit from bringing on a professional project manager just for the project. Get a bigger down payment. Schedule invoicing more frequently, and require payments be current before each phase begins.

The risk you're left with drives up your price, and this is entirely reasonable. It does a couple of very valuable things for you. For one, you might not get the job, and depending on how much risk there is, this may be a Very Good Thing.

If the job has significant, unmitigated risks, give it a "walking away" price. Don't put a lot of effort into quoting the job. Bump up the risk to an appropriate level based on the problems with the job and your less-well-considered quotation, and send it over without expectation.

Then, if you do get the job and things start to head south, you were already being paid extra to deal with it and you can take it on with a smile. Scope creep? No problem - you expected it. Plus you can still try to get paid for it. Stiffed you for the last payment? That's okay, the last payment was the second half of your bonus, not your paycheck. The client is a pain in your butt? You charged the asshole tax up front.

slide

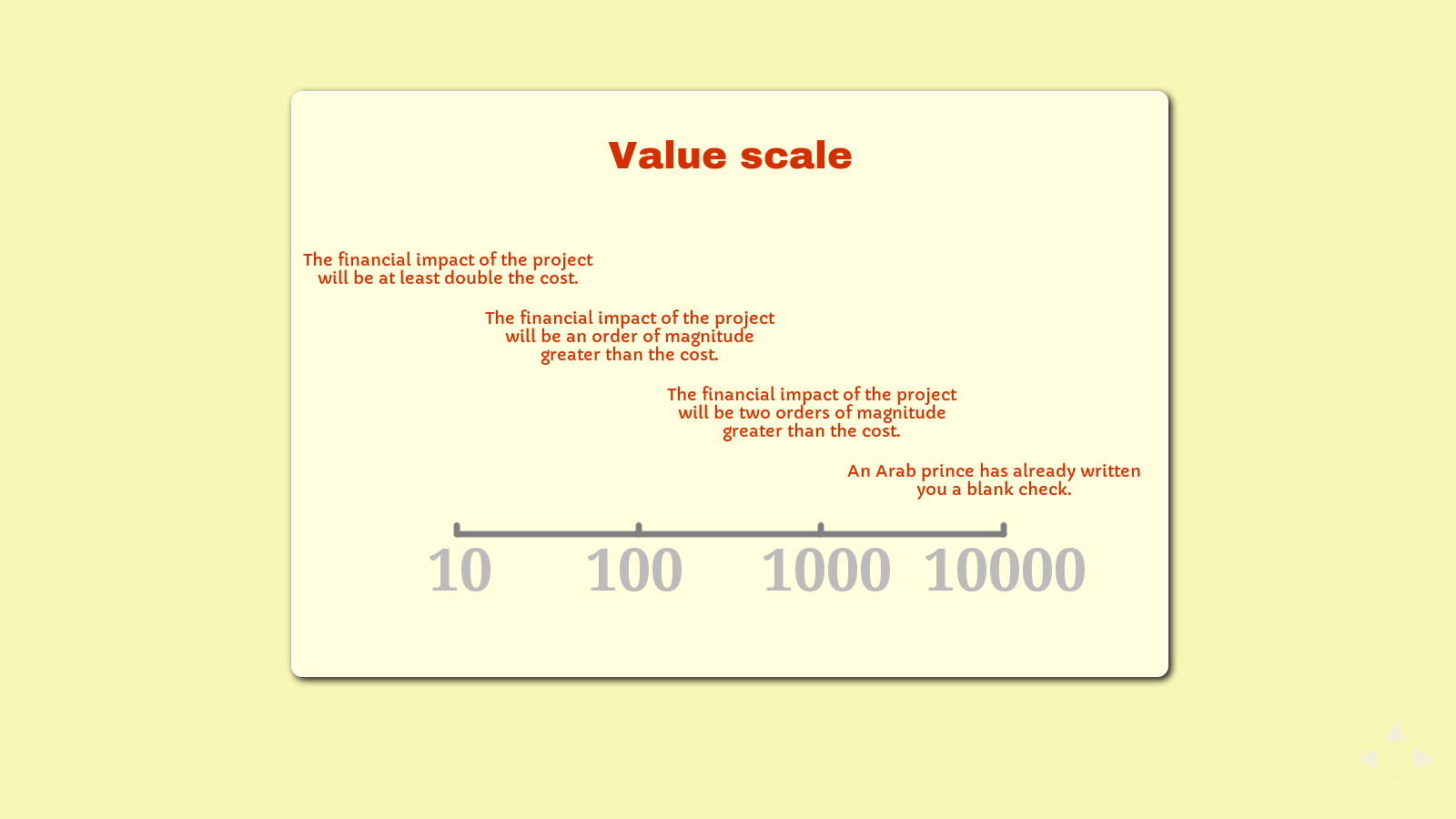

Evaluating value

- 10 - The impact of the project will be at least as great as the cost.

- 100 - The impact of the project will be an order of magnitude greater than the cost.

- 1000 - The impact of the project will be two orders of magnitude greater than the cost.

- 10000 - An Arab Prince has already written you a blank check.

slide

My microeconomics professor at the University of Maine was a fish economist. He told us how he'd been approached by Heinz Corporation way back in 1969 to assess the potential market for cocktail sauce. They asked him for a daily rate, and he gave them a price of $100 a day.

He didn't get the contract. They found someone who'd charge them $1,000 a day.

I've worked on big websites for small companies that cost $20,000. I've worked on small websites for big companies that cost $20,000. When it comes down to it, people want to pay a price commensurate to the value they get.

I told you up front you need some business instinct to use this model. That's perhaps most true when it comes to figuring out the value your client will gain from your work. Understanding that number will do much to free you from hourly drudgery.

Don't do work that has limited value.

If the potential gain is small, your client needs to think small, and treat you small. It makes your job much less enjoyable.

If the potential gain is large, your client is motivated to make big things happen with you, and will support you on the project. It makes your job much more enjoyable, and lucrative too.

It boils down to this: Always. Maximize. Value.

slide

How to discount your work:

- Look for snacks, not huge meals.

- Quote full price and then apply a discount.

- Your discount may be a marketing expense. Talk to your accountant.

slide

We have one more factor that we could have added to our formula, but if we did, it'd be there strictly to help you undo the benefits of using a pricing model like this at all.

Sometimes it doesn't matter what you know you should charge, you really need to get the work. Or at least some work. I propose it's still best to know what you should have been charging, and then discount it, rather than ignoring good sense and pricing the work artificially low.

"Hunger" is that factor. The hungrier you are to get the job, the more you'll knock of your price to make sure you get it.

Obviously the best bet is to keep hunger at bay. But since that's often not possible, I have a couple of suggestions that may be helpful:

- If you're hungry, look for snacks, not huge meals. Once you get something in the pipeline, that sense of hunger is going to start going away. You don't want to be paying for it long term. Sometimes you can even turn a big job into a snack. For example, it may be beneficial for everyone if you got paid for a 40 hour discovery project and use that to spec out the big job at regular price.

- Quote your work at full price and then add your discount as a line item. Offer a new client a "new customer discount". Apply a coupon. Do a cross-promotion with your client. Your client gets the price they need, but you're instilling an expectation about your future charges.

- Talk to your accountant. It's possible that discount you're giving might actually be a marketing expense, and this might improve your tax situation.

slide

nested CRV

slide

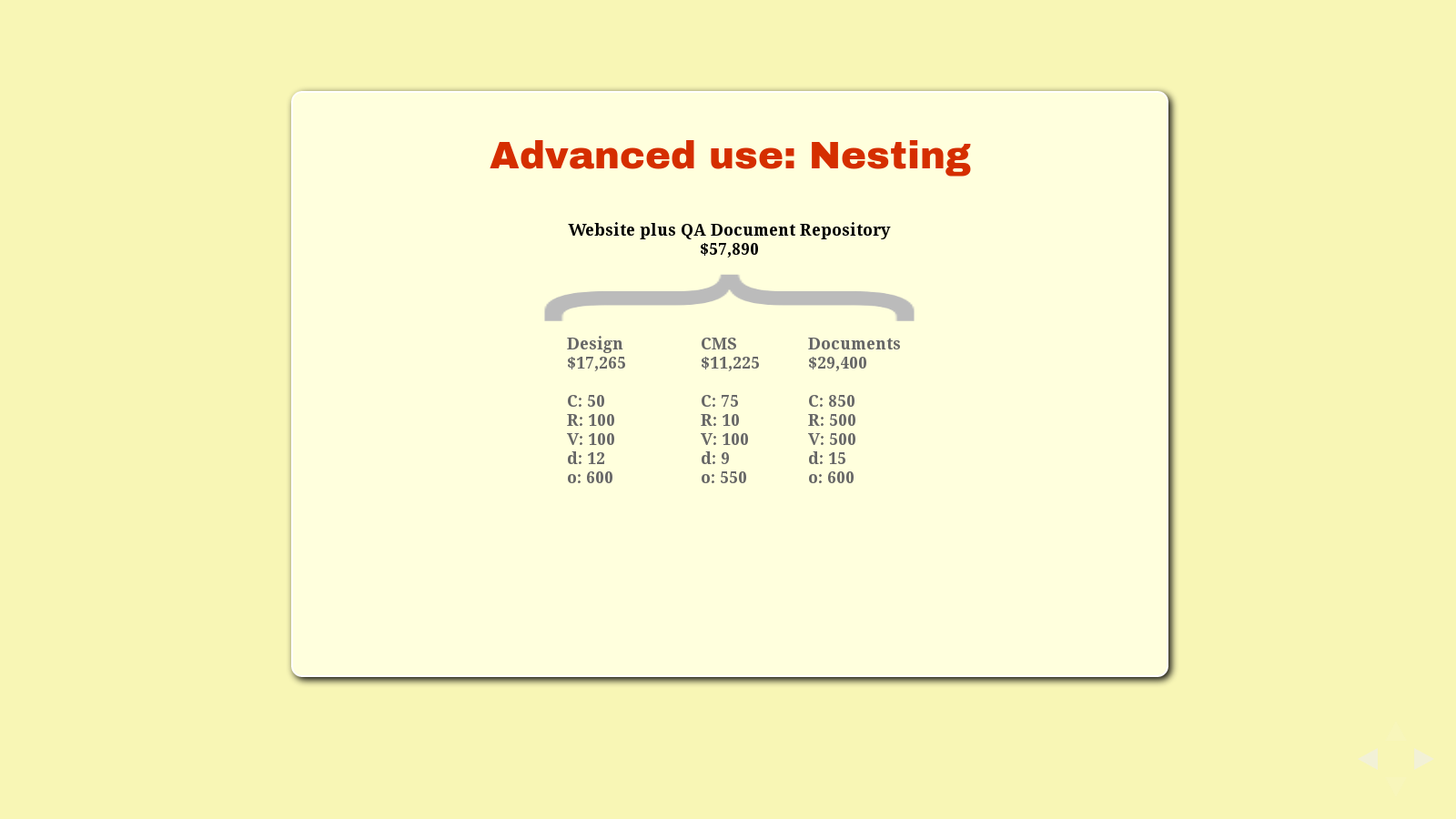

I'm just going to throw this out there. You don't have to use the same complexity, risk, and value factors for every part of a project. You can break the project into meaningful pieces and apply the model to each piece.

For example, let's say we're quoting a new website for a heat treating company. Most of the project is straight up design and implementation, but they also want their customers to be able to log in and retrieve quality documents about previous jobs. To do that, you need to tie into their internal document management system running under Microsoft Dynamics.

Now we have a project that involves two kinds of CRV profiles. The web site is relatively easy and moderately valuable, but the document retrieval system is significantly more complicated and valuable. Depending on how much experience your team has with Microsoft Dynamics, it may also add a bit of risk.

slide

Ideal Cost: o * d

CRV Factor: log10 ( C + R + V )

slide

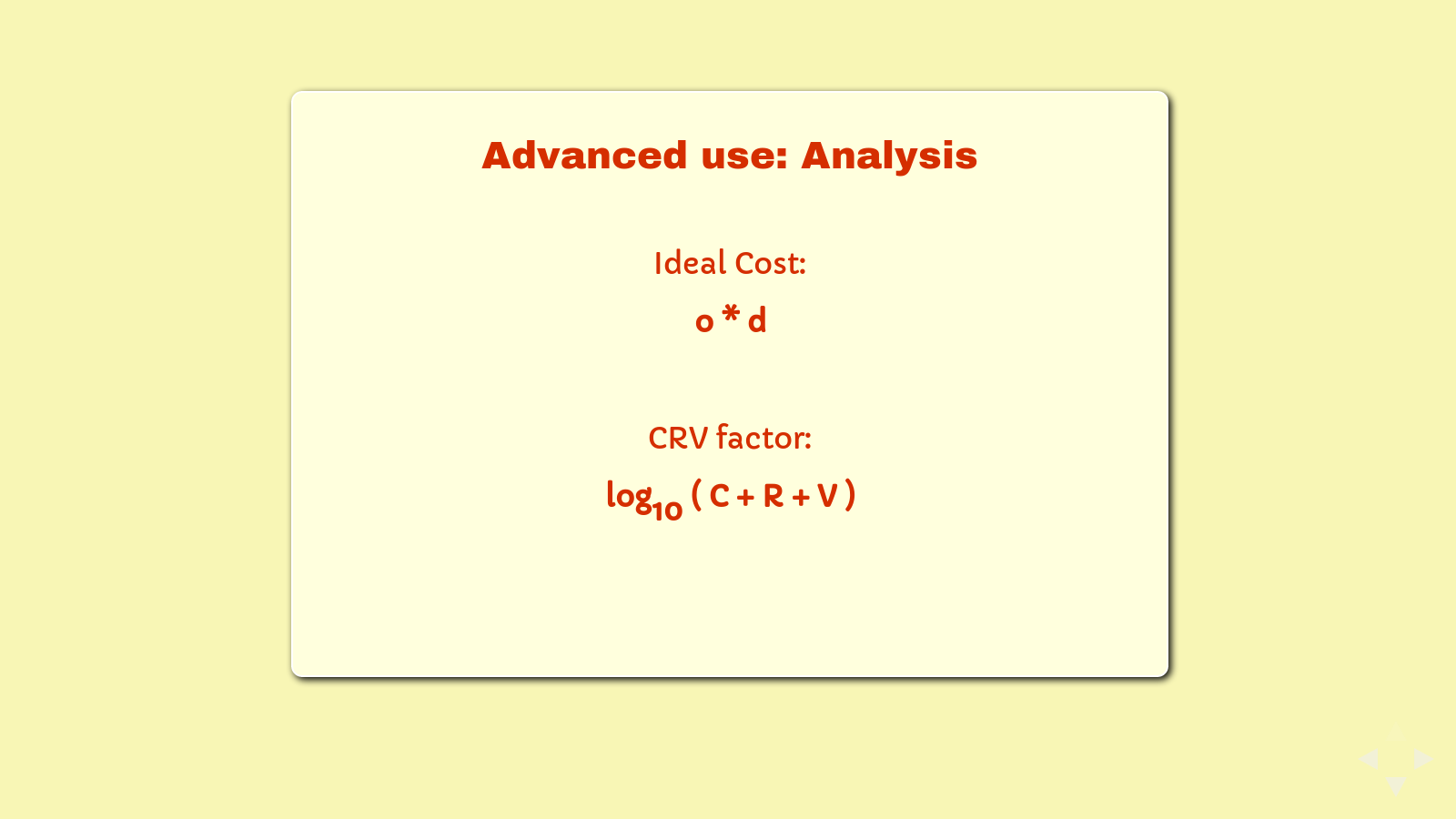

You may have noticed that two terms make up the heart of this formula.

I call the first one "The Ideal Cost". It's your overhead rate times your time commitment. That's what the job should cost you assuming everything goes swimmingly.

I particularly like the concept of Ideal Cost. We humans are notoriously bad at making predictions. Our emotions get in the way. Ideal Cost eliminates some of that problem by removing the complexity of the negative emotional factors. We don't have to think about what might go wrong at this point - we get to consider just the positive. And this is a nice way to think about a new project.

The second term is the "CRV Factor" is your multiplier on the Ideal Cost. It builds in supply and demand, mitigates your risk, and keeps your price commensurate with the value of the project to your customer. The higher the CRV Factor, the higher your total price.

Let's look at some ways you can use the CRV Factor to quickly analyze almost any project.

slide

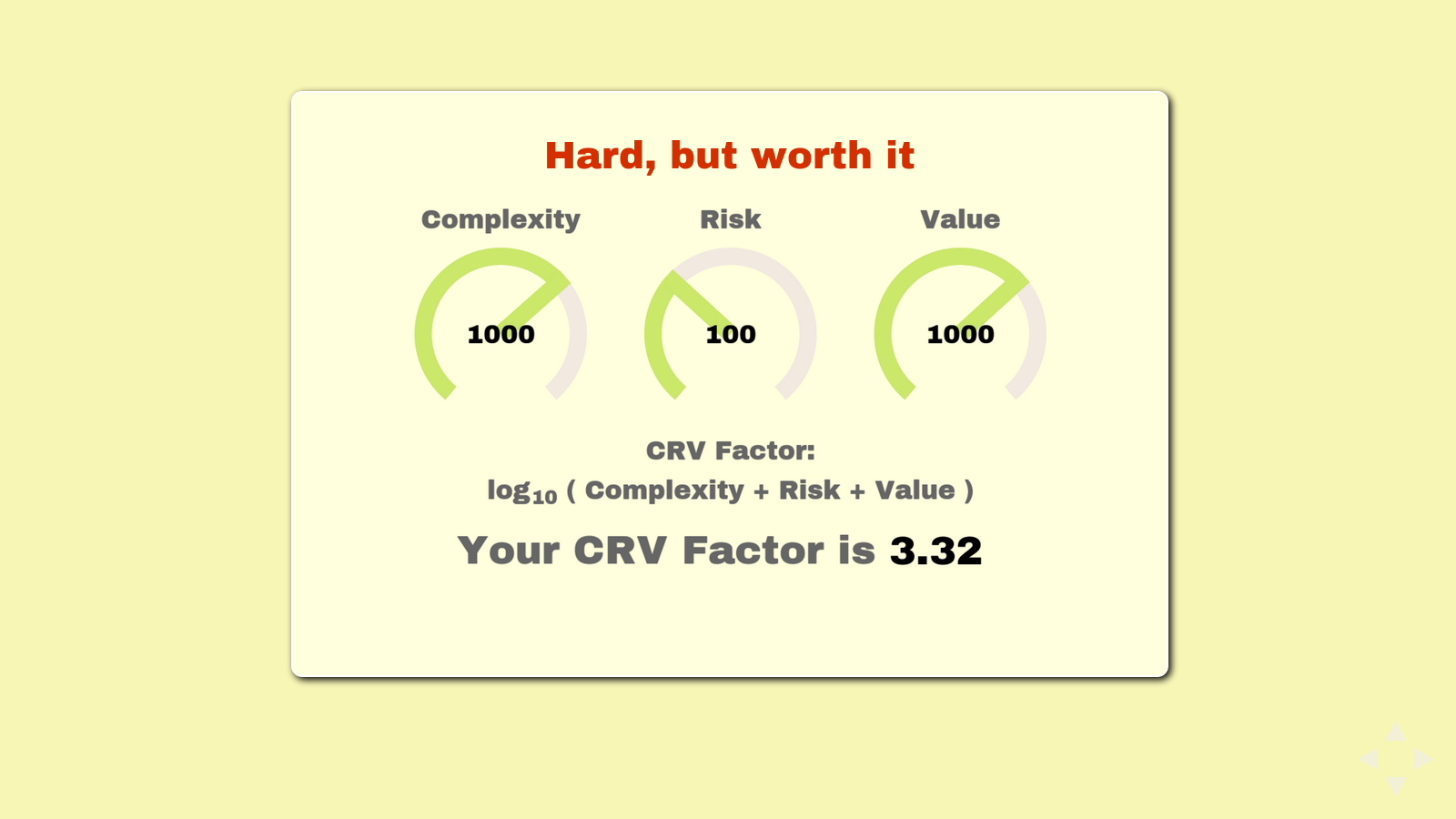

- Complexity: 1000

- Risk: 100

- Value: 1000

- CRV Factor: 3.32

Hard but worth it.

slide

You're a specialist in a valuable field. Your clients are lucky to have your attention.

slide

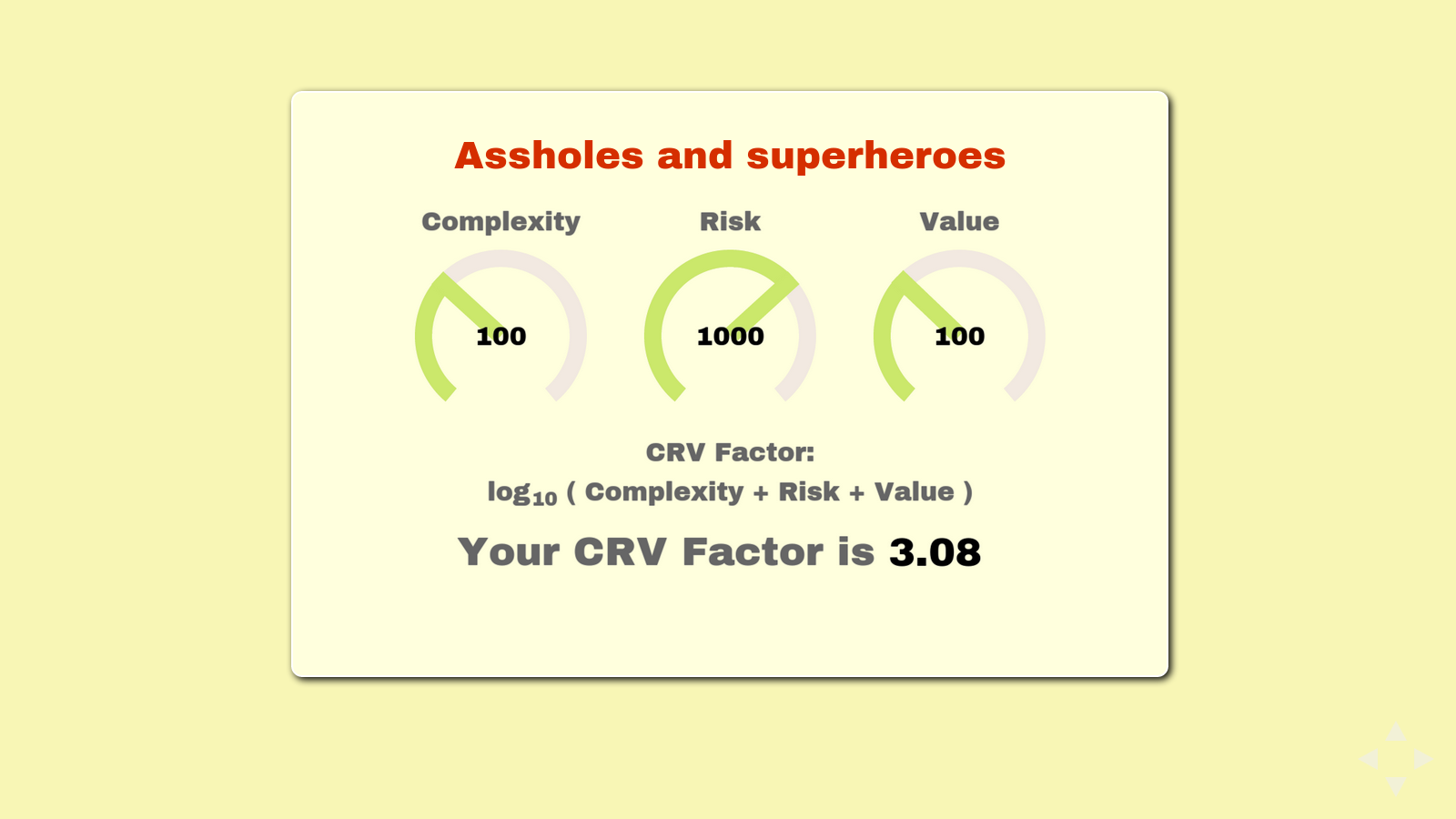

- Complexity: 100

- Risk: 1000

- Value: 100

- CRV Factor: 3.08

Assholes and superheroes.

slide

We've probably all worked on this project, right? It's a good fit for your skill set, and it's quite worth while for your client, but your client is an ass. Or doesn't have the money. Or needs it next week.

The nice thing about these jobs is this: you get to be the superhero, and if you're willing to work under these pressures, you can really shine.

slide

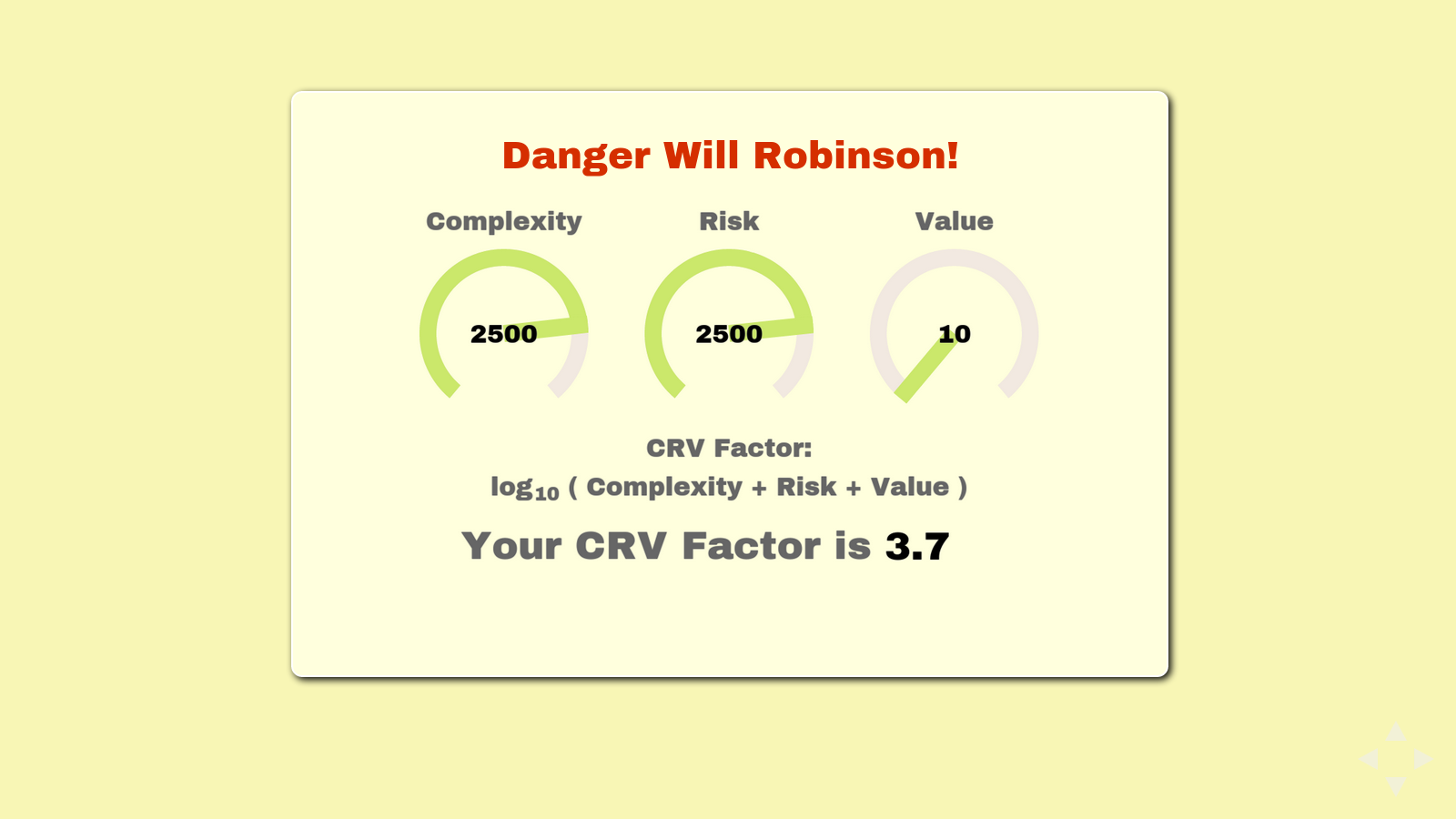

- Complexity: 2500

- Risk: 2500

- Value: 10

- CRV Factor: 3.70

Danger Will Robinson!

slide

Sometimes I feel like every job I quote looks like this. I can't think of anyone else getting it right, but the risks are significant and when it's done, the client isn't going to get their money's worth anyway.

These are the jobs you refactor for your customer. Drive the complexity down. Mitigate more risk up front, maybe by doing a discovery phase. Shift the priorities so there is more value in the final project.

Make this project a better project, or embrace the multiplier of almost four and hope they decide you're too expensive.

slide

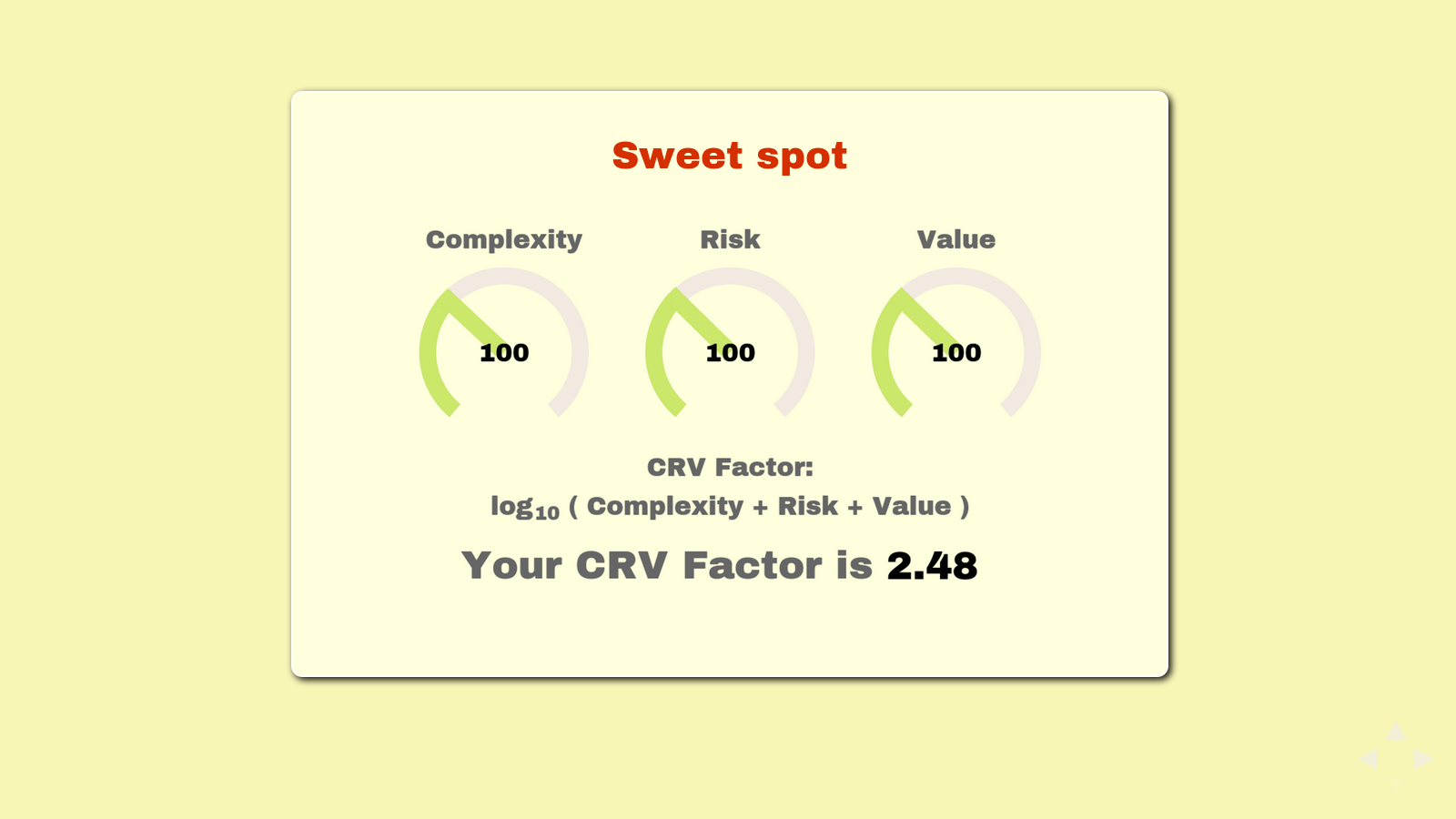

- Complexity: 100

- Risk: 100

- Value: 100

- CRV Factor: 2.48

The sweet spot.

slide

I like these jobs: Competition's not too tight, the job has manageable risks, and it's going to be worth it to your client. It's a factor of almost 2.5 times your Ideal Cost. You can afford to hold out for the jobs you want. You enjoy your customers and your work.

slide

@version2beta

http://twitter.com/version2beta | http://version2beta.com

CRV Factor Calculator: http://version2beta.com/static/examples/managing-risk-and-selling-value/crv-calculator.html

Tech support is always free!*

- Free as in beer. Means you buy me a beer and I give you tech support.

slide

I want to remind you that this formula is a model for pricing your work. It helps you understand your client, the project, and your self. Along the way it may make you a better businessperson. It's a framework for thinking about the work you do.

Thank you for listening. As always, my presentations come with a 100% money back guarantee plus tech support that is "Free as in beer". That means you buy me a beer and I give you tech support.

Bucketworks is a health club for your brain. It's space for your community, your business, or your meetup. It's a physical wiki. Bucketworks is cool. ↩

[Reveal.jsreveal is a very cool HTML & javascript presentation tool. It's been easy to work with on all fronts. ↩

A formula for calculating an order quantity that minimizes the total holding and ordering costs. ↩

Agile Software Development attempts to shift the focus of work. Two good places to start learning about Agile are the Agile Manifesto and the Twelve Principles of Agile Software. ↩

The logarithm (or log) of a number is the exponent you'd put on a base number like 10 or e to get that number. For example, log10(1000) is 3, because 103 is 1000. ↩

Cost accounting tries to evaluate production in terms of direct and indirect costs. Traditionally, it views labor as a direct cost. ↩

Throughput accounting is a simplified managerial accounting model that focuses on simple measures that drive behavior in key areas toward organizational goals. While I was trying to figure out how to describe this, I also found an interesting article in Forbes Magazine about explaining Agile to the CFO using, in part, Throughput Accounting. ↩

I used C2 as an example here because I know them and have worked with them. They're good people. ↩