This is my presentation on selecting open source libraries by paying attention to the people behind them. I presented this at That Conference[1] in the Wisconsin Dells on August 14, 2013. I was very pleased by the compliments this presentation received. Here are a couple of them:

As always, I write my presentations out in advance, in long form. I think of it as my "ideal transcript" - what I meant to say before I actually started stuttering my way through it. I'm sorry to say this conference did not record video.

You can also see my slide deck.

Hi. I'm Version2beta. That's 'version', the number 2, 'beta', and it's short for 'Life, version 2 beta'. It's my handle most places online.

In meat space I'm also known as Rob, and under a few select circumstances, Dad.

My contact info will be on the last slide too, so don't worry if I zip past this one.

Smell is strong.

I don't mean the smell in this room. I mean that olfaction, our sense of smell, is a powerful sense. It's potent in the moment, sometimes overwhelmingly so, but it's also tightly coupled with our memory - especially our emotional memory. Very often a certain smell will be accompanied by a feeling of safety or fear, love or anger.

I still remember the way this girl in high school smelled. We were at a forensics competition, regionals, and we both got knocked out before lunch. We weren't going to state. Instead we went to the gym, where we played this backwards egg toss game. Every time we caught the throw, we'd move closer together. I still remember how she smelled. I also remember how it made me feel, but we won't get into that.

Turns out we have this thing in our DNA called a Major Histocompatibility Complex, and we can smell it in each other. Histocompatibility is a quick way for us to tell - by smell - whether we have compatible immune systems. My wife has known about this for years and readily admits the sniff test was the first thing she did when we met. I am very pleased to report that I passed.

Despite what we say about code smells, this sniff test may be better for selecting a mate than for selecting an open source library, or even an open source library programmer. But keep this smell stuff in mind. This presentation is about connecting with people authentically, and sometimes that means getting close enough to smell them.

Let's do that now. Take a moment and smell someone near you. Really - I'm not kidding. Smile nervously if it helps. Say something awkward - that's how most people do it. But one way or another, turn to someone near you and smell them.

This presentation is about forming authenticate connections with other programmers, specifically the ones who write the code libraries, modules, plug-ins, add-ons, etc. that you use every day. It's about finding new programmers to connect with and using those connections to help identify new libraries you need.

I'm not suggesting you adopt an open source developer. That sounds patronizing.

I'm not suggesting you befriend an open source developer. That sounds pitying.

I am suggesting we recognize that we are already in interdependent and mutually valuable relationships with the developers of the libraries we use. I am suggesting that we honor those connections.

We won't do it because it's a good idea. We will do it, and we are doing it, because it's part of making what we do and who we are into a single, holistic experience.

Let's shift for a moment to software, to picking out an open source library.

Did you know that Drupal.org lists over 23,000 freely-available modules? Let's say your employer wants you to be an expert on all the available Drupal modules, and is willing to let you spend a whole ten minutes learning what makes each module unique and useful. There's job security in this project - it will take you two years working full time to get through them all, not including the new ones that are released while you're working on the project.

Do you use Wordpress? You have more than 26,000 plugins to choose from, just at wordpress.org. Nearly 4,000 of these call themselves a "widget". Surely there should be a plugin for almost anything you need, but finding it is a needle in a haystack problem.

Are you a javascript programmer? As of today, there are over 37,160 libraries in the npm registry. Need a library for logging? There are nearly 2,000 of them.

I'm a Python programmer, and I have five open source libraries I wrote and maintain in PyPi, or "the cheese shop". But the cheese shop has almost 35,000 libraries, so for every one of my libraries, there are nearly 7,000 maintained by other people. Or not maintained at all.

I used to be a Perl programmer. Thankfully I do not have a job that expects me to know all of the Perl open source libraries. CPAN, the Comprehensive Perl Archive Network, indexes almost 125,000 modules.

When we're looking for a code library, we pay attention to several characteristics.

We need to know that it will do what we need. Those are typically features of a code library.

We might consider whether the project is actively maintained. Commit frequency is useful for this. A project that hasn't been updated in a while is probably not actively maintained. Or maybe it's stable and doesn't need to further development.

We'll often rely on our peers to show us which cliff to jump off, so we might look at the number of times other people have downloaded a library, or the rating other people have given it, or maybe just how many people favorited the library.

We want to know that the programming is reasonably well done, so maybe we'll evaluate the code quality. If we have time. After all, if we rely on the library and the developer doesn't maintain it, we might be stuck fixing the code.

When we choose to use a library, we are also choosing to create new interfaces, new edges, in our code and our process.

Just to clarify, most of the time when I say edge I'm referring to graph theory. You see it all the time in network diagrams. You have nodes connected by lines to other nodes. The lines are called edges. How and where they connect are interfaces. What's true in mathematics is almost always true in life too, so when you hear me say something like "All the interesting stuff happens at the edges," I'm not limiting myself to network graphs.

Okay, back to coding.

- There is an edge between our code and someone else's code.

- There is an edge between our coding practices and someone else's code.

- There is an edge between the needs of our project and the needs that the library was written to address.

- There an edge between ourselves and the developer who wrote the library.

- There is an edge between our needs and the developer's needs.

- There an edge between our expectations and the developer's expectations.

When things go well, the edges mesh together beautifully. But when they go poorly, we get the kind of grinding you hear from a teenager in a car with a manual transmission. Instead of interfaces, the edges represent conflicts.

So we have gears that aren't meshing. We have interfaces that have crashed into one another. We have conflict in our code, in our needs, in our expectations, or even between us and the developer. How do we resolve that conflict? Or a better question, how do we avoid it?

I've had the opportunity over the past decade or so to watch a number of Bollywood films. If it helps, take a moment and picture me dancing around the living room, singing along in Hindi.

My wife discovered this interesting difference between Bollywood films and American films. In American films, when the guy first sees the woman, he sizes her up with that cultural male gaze, and he judges the potential for a hookup. In Bollywood films, when the guy first sees the woman, he also sizes her up with that male gaze, but he judges her potential as a wife. He pictures her in her wedding gown, all hennaed up. He pictures her feeding him, being subservient to his mother, being gal pal with his sister. If it's a particularly racy Bollywood film, he'll picture her in his bedroom with a single bare shoulder.

Believe it or not, when we select an open source library, we do the same thing. We project the satisfaction of our needs onto the object of our desire. I mean the code library of course. The library - and the woman in the movie incidentally - is really just a reflection of ourselves. And like the man in the movie, we are often disappointed once we have real experience with the code.

Therein lies the conflict - we have expectations, and they might not be compatible with the code. The resolution of these conflicts comes from understanding the developer's expectations as well as our understand our own. And that understanding comes from connection, which in turn comes from trust.

The really tough question is, who can we trust?

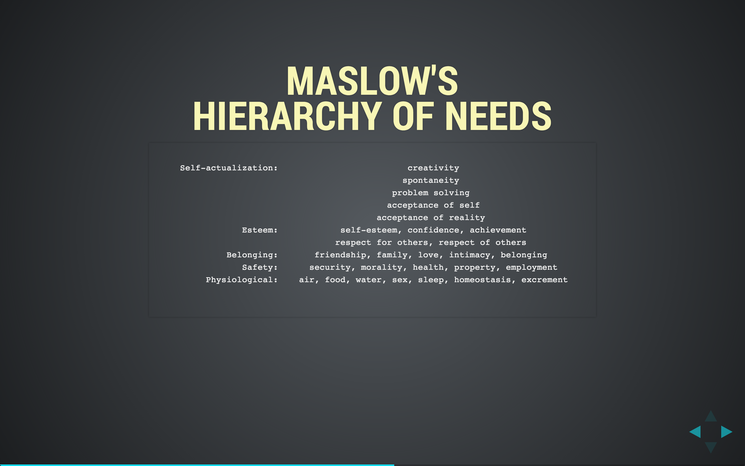

We can often understand someone's motivations and expectations if we understand their needs. Abraham Maslow helped us organize those needs into a hierarchy. Conveniently and memorably, it's called Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs.

Since we're relying on Maslow's work, let's quickly introduce him. If there's one thing I hope you take away from this presentation, it is to learn about the people upon whom you are relying.

I'm sure you've already heard of Maslow's Hammer. He originated the phrase, "it's tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as a nail."

Abraham Maslow grew up in Brooklyn, the oldest of seven children of Jewish parents who fled Russian persecution. As a child, he was bullied mercilessly, much of it anti-Semitic. A psychologist at the time classed him as "mentally unstable". As an adult he became one of our most important research psychologists, teaching at a slew of excellent schools, including Brandeis, Brooklyn College, the New School for Social Research, and Columbia University. Throughout his life, he had a horrible relationship with his mother, which may have contributed to his interest in understanding people's needs. Maslow had a massive heart attack while jogging and died at age 62. I was not yet a year old when that happened.

Maslow created a pyramid describing human needs. At the bottom we have our basic physiological needs, like eating and drinking, peeing and crapping, breathing, sleeping, and sex. Once our physiological needs are met, we are better able to focus on our higher level needs, like being safe and healthy, having a secure home and job, and maintaining a moral code. After we've addressed these needs of our body and our future, we can truly start to work on our sense of belonging - having friends, intimacy, love, and family. Once we have stable social structures, we turn inward and work on our self esteem, self-respect, and sense of achievement. Finally, after we've found ways to satisfy all of these needs, we address our need to be self-actualized, to accept our role within reality and our responsibility to help create the world we live in.

Generally speaking we can use Maslow's hierarchy to understand ourselves and other people. We are all human, we all have needs, and we all need each other. We need each other.

Let's get back to some of the interesting stuff that happens at the edges.

Where there is an edge, there is potential for conflict.

What we need instead of conflict is connection. This is well demonstrated by Maslow's hierarchy. We need to know we belong. We need to hold ourselves in high esteem. We need to be self-actualized. When we work, we are actively meeting these needs and others. When a developer writes a library, she is also meeting these needs.

When we use a library and connect with the person or community behind it, we are meeting these needs together. This builds the connection that replaces conflict. It is the foundation for understanding and trust. It is self-actualization. One-to-one, it is us creating the wholeness of our selves.

We each are part of larger social networks. Sure, this includes Twitter and Facebook and LinkedIn, but it also includes our friends and lovers, our coworkers and cohorts.

Quick review of graph theory: the connections between us are edges, and we are each a node. You might find it interesting to know that "node" comes the Latin word "nodus", which means "knot", as in your node is the spot where the edges are tied in a knot. That's how it goes: You are in the network. You are surrounded by edges. You are tied up.

Robin Dunbar - Robin Ian McDonald Dunbar - has put together some really excellent research on how connected we are.

Dunbar is an anthropologist and evolutionary psychologist, which is pretty much what I want to be when I grow up. Unless I become a farmer instead.

Among other achievements (like being a department head at Oxford University) he has a number named after him. It's called Dunbar's number, and it basically represents an approximate number of people with whom we can maintain stable social relationships. It's suggestive of our cognitive limit to connect. Dunbar's number is commonly accepted as 150, meaning that we can maintain stable social connections with that many people.

In reality, Dunbar's number isn't a single number, it's a range from about 120 to 230. According to his most recent research, the actual value of the number for any given individual depends on that person's "social brain" - specifically, the orbitomedial prefrontal cortex. In fact, Dunbar's 2012 paper has demonstrated a correlation between the size of an individual's orbitomedial prefrontal cortex and the size of their social networks.

My wife and I often talk about our children's underdeveloped prefrontal cortices, and how it's our responsibility to provide that capacity for them. But what does our prefrontal cortex do?

First and foremost, as demonstrated by Dunbar's research, the prefrontal cortex does our social information processing. It helps us keep track of the people with whom we are connected. It's where our theory of mind lives - the ability to recognize that other people have their own experiences, and that their experiences are different than our own.

It's also where we do our planning, both short term but complicated motor planning like tying a shoelace, and long term and even more complicated planning, like me becoming an anthropologist and evolutionary biologist. Or maybe a farmer.

The prefrontal cortex also houses our working memory - the mental stuff we're actively chewing on.

If you're still listening to me, that's also because of your prefrontal cortex. It's responsible for our attention.

Far from least, the prefrontal cortex is a processing center for language and symbolic thought.

Here's something interesting to point out. Every one of these functions are also important to us as developers. We use the same mental skills keeping track of code objects and passed messages that we use keeping track of social networks. We are constantly planning, whether it's keeping track of the current sprint or the next line of code we're going to type. Figuring out that next line of code totally taxes our working memory, and getting it down on the screen is all about language and symbolic processing.

Contrary to the stereotypes, we developers are all about the prefrontal cortex. We are jacked into that network. It's not just how we relate; it's where we live.

Want to hear something really interesting? The prefrontal cortex, specifically the orbitomedial region, is also responsible for olfaction. Our sense of smell.

Feel free to smell your neighbor again.

As you might imagine, there has been a lot of recent work into figuring out what connections are worth.

One of the earlier rules came from Robert Metcalf. You might recognize that name. He graduated from MIT with two bachelor degrees about a thousand years ago, the year I was born. He was so impressed by Arpanet (a predecessor to our current internet) that he made it the topic of his PhD. dissertation at Harvard. They flunked him, and then he went on to co-invent ethernet and start a company called 3Com.

Metcalf's Law says the value of a telecommunications network is proportional to the square of the number of connected users.

David Reed was also educated at MIT, just a couple years behind Robert Metcalf. In the 80's he was an assistant professor there, and since then he's been a visiting scientist at the MIT Media Lab, America's foremost school of wizardry. David Reed invented UDP, though he finds that statement a little absurd since what he really did was co-invent TCP and then decide it might be nice to make a simplified version too.

Reed's Law says that the utility of large networks, particularly social networks, increases exponentially with the size of the network.

Rod Beckstrom is a relative youngster, only 52 years old. He's a Stanford grad and spends a lot of time thinking about organization theory. For a while, he directed the National Cyber Security Center, but he quit when the NSA decided they were in charge. He's also run ICANN, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers, and he's on the board for trustees for the Environment Defense Fund. One of my favorite things about him is that he presented Beckstrom's Law at DefCon, the world's largest underground hacking conference.

Beckstrom's Law says that the value of a network equals the net value added by each user's transactions conducted through that network, multiplied by the number of users.

So at least these three experts agree that networks get more valuable as they grow, and the value increases non-linearly. The more connections you have, the bigger the payoff.

This value is not retained solely by the people who own the networks. If that were the case, we wouldn't use their networks, would we. We use Facebook and Twitter and LinkedIn and Github because they provide value to us. And the value of the network to us personally goes up as our network grows, typically at least until we get somewhere around Dunbar's number.

I'm going to back this up with anecdotal evidence.

I'm not a particularly strong programmer, but for over two years I've made a point of trying to get better in part by knowing the people who write the libraries I use and put on the podcasts I learn from. About a year ago, one of those people heard I was looking for a job and said I should come interview at the place he works.

I said no, I'm not a good enough coder.

I worked my ass off for nine months, learning to be a better coder, and then I tweeted back at the same guy. He took time out from an embedded Javascript conference he was attending to talk with me on IRC. He got me an interview with five engineers at their place - the kind of place where the engineering team decides who they want to work with. That got me a plane ticket and two days of pairing at the office. That got me an offer that met my every need, including moving halfway across the country to one of the most beautiful places I've ever lived.

Now I'm working at a place that let Github, Valve, and TED inspire their employment manual. I make enough money to live the way we want to live. I don't have set hours. I don't have set vacation - if I need time, I let my coworkers know and they cover for me. I pair practically every day. I get a day a week to work on my own projects. If I think a conference is going to make me better at my job, or a better programmer, or just more creative and in touch with the world, I just ask for it. And since I'm not a foosball player, I work on my 9-ball skills at the office instead.

I didn't do any of this on my own. I connected with other people - open source developers who maintain libraries of their own - and they helped make it happen. I love my job and I have no interest in looking for another, but I know me and my network are still going places. For instance, this month I'll have my first article published in a programming journal. This is cool for me - I like talking and I like writing, and someday I'd even like to write a book.

Enough about coding. Let's talk about food. Food as a metaphor, at least.

Many of us buy our food from the grocery store. We look at the tomatoes and check out their color and feel their firmness and decide which ones we want to buy based on the characteristics of the fruit. That's the typical way of choosing open source libraries, too.

Some of us are "foodies", though. Maybe you live in Madison, or Milwaukee, or even Salt Lake City like me. I don't want you to go to the store and check out the fruit. I want you to go to the farmer's market and check out the farmers. Get to know them. Go volunteer to work on their farm. Try to understand what they're choosing to grow and why they grow it. Is that heirloom tomato a specialty, or was it a one-time experiment? Where is the parsley? What happened to the potatoes they used to sell? You only know these answers if you know the farmer.

The same goes for your coding. Instead of a physical location, your community is the group of people who work with the same code base, be it Wordpress or Joomla, Python or Ruby or Node.js. Get to know the farmers in your community, and learn which libraries are their staples and which are experiments. Learn what's important to them, and go back to their code base when you're looking for something new.

After all, we're not here at this conference because we want to buy the tomatoes. We're here because we want to become farmers, and you don't become a farmer by studying the fruit in the supermarket.

Like most projects, this one was a collaboration with a number of other people. Many ideas on this topic come from years of conversation with my wife. The place I'm working has been an entirely positive influence on my thoughts. A number of people helped me compose and edit the presentation. Some of them sat patiently through my practice and provided excellent feedback.

I have relied on these people, and I appreciate their roles in my life.

If you want to discuss these ideas further - or you want to disagree with me - please feel free to drop me a line. If you don't mind me quoting you, please tweet at me. This presentation, with a transcript, is already up on my website.

I'd like to thank you for your attention, and I hope the ideas I've presented are helpful to you.

That Conference (really, it's called That Conference) is a summer camp for geeks held in the beautiful and touristy Wisconsin Dells. My presentation is listed under Navigating the Bazaar. ↩