I prepared this lightning talk to present at PyCon 2013[1] on March 16 in Santa Clara, California. Unfortunately, talks were selected at random. I wasn't selected Saturday evening, and even though I was select Sunday morning, apparently I was in the overflow list in case others didn't show.

Surely I'll have opportunity to give this talk somewhere. Meanwhile, it's here for you.

My slides are available online here and as usual, this is my "intended transcript" - the way I meant it to be, before I messed it up by actually presenting it.

Data represents reality.

Maybe just a small slice of it, but data is a slice of reality, and it's packed away inside of a database.

Databases model our world. Practically every electronic representation of the real world is in fact some kind of database.

If you use a computer, or are a customer of almost any company, then there is a database that models you.

As models go, databases lack a lot. They tend to store only what they expect to need. They often store that information poorly, trying to squeeze the world into a set of tables like putting an elephant into ballet shoes.

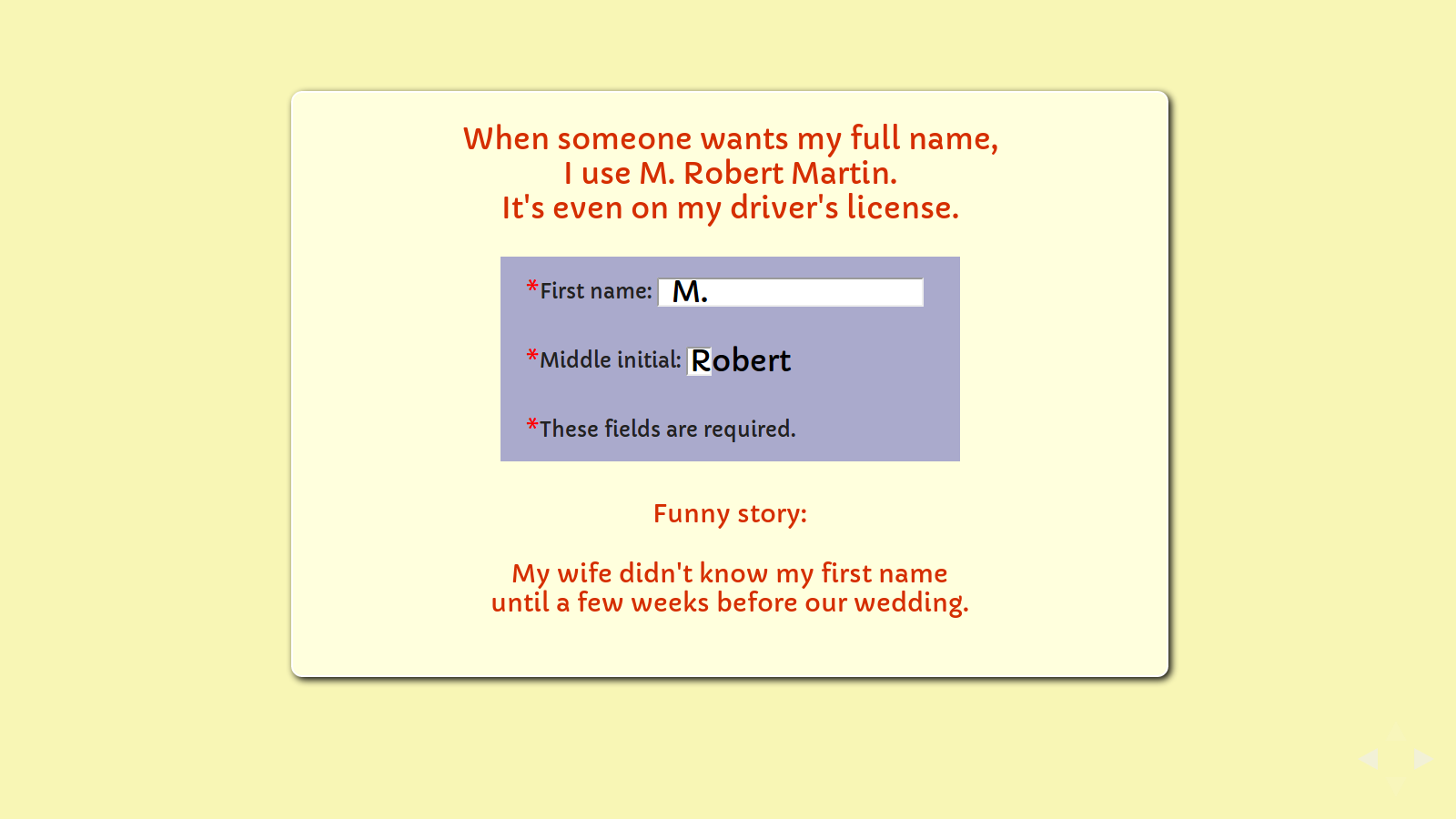

I use my first initial and my middle name. I get squeezed into databases all the time.

Many of us are developers, and we build applications that are database doorkeepers and data validators. Our job is to build that toddler's toy that turns star shaped cylinders into square blocks.

The short-sightedness of a database's design can lead to all sorts of misadventure. I laugh when my wife gets mail that has my name as her last name. Not even my last name. My first name as her last name.

It's funny when we're talking about junk mail, but try standing at an emergency room counter explaining why your insurance card has the wrong name on it.

This is, of course, our fault. Us, the developers and architects and thinkers about this model of our world.

We design databases based on our subjective understanding of the parts of the world we need to model.

Our subjective understanding is informed by culture, and because of this we often encode culture into our database.

Even today it's hard for my wife to create a joint account for us that doesn't list me as the first and primary account holder.

The database distorts reality to fit its limited ability to model the world. As a result, it changes how we describe ourselves. It changes our story. And when we change our story, we change our selves.

That is the tyranny of the database.

I want us to do better. We have the storage space, the performance, the bandwidth, and the programming skill to build databases that are informed by behavior and observation.

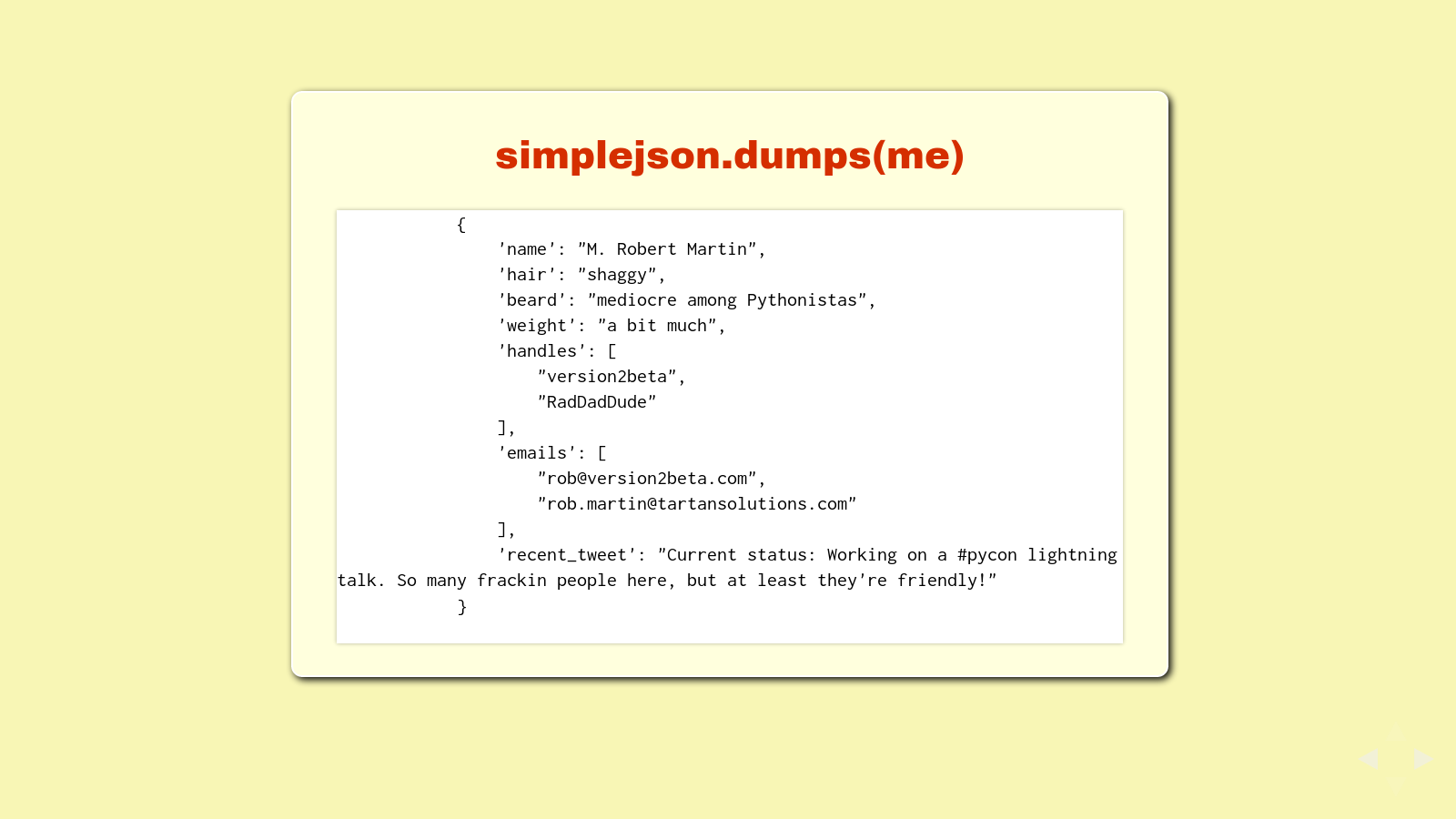

Here is a JSON document that represents me.

I picture how this document could be the product of a call to a service. Maybe this service is backed by PostgreSQL, or by someone else's API, or maybe it's flat files. This document doesn't need to be drawn from any one data source at all. We can make it richer by pulling data from other services and merging them into one document. It's no longer a join so much as a mixin.

I call this data Arbitrary. I want to even further decouple the database from the application. Let's make fewer objects and more services that can become richer and better over time.

Let's look again at the document that describes me. What's your app supposed to do with all of that?

Start by using what you can, what you recognize as relevant data, but approach it semantically. Be prepared to look for data in more than one place. Coalesce from multiple sources.

Silently set aside the data that isn't relevant. It's what our brains do, a thousand times a minute, in the real world.

Gracefully accept what you don't know. Write tolerant code that recognizes that data has holes. And when you can, make your software help fill those holes to build a richer, more complete model of reality.

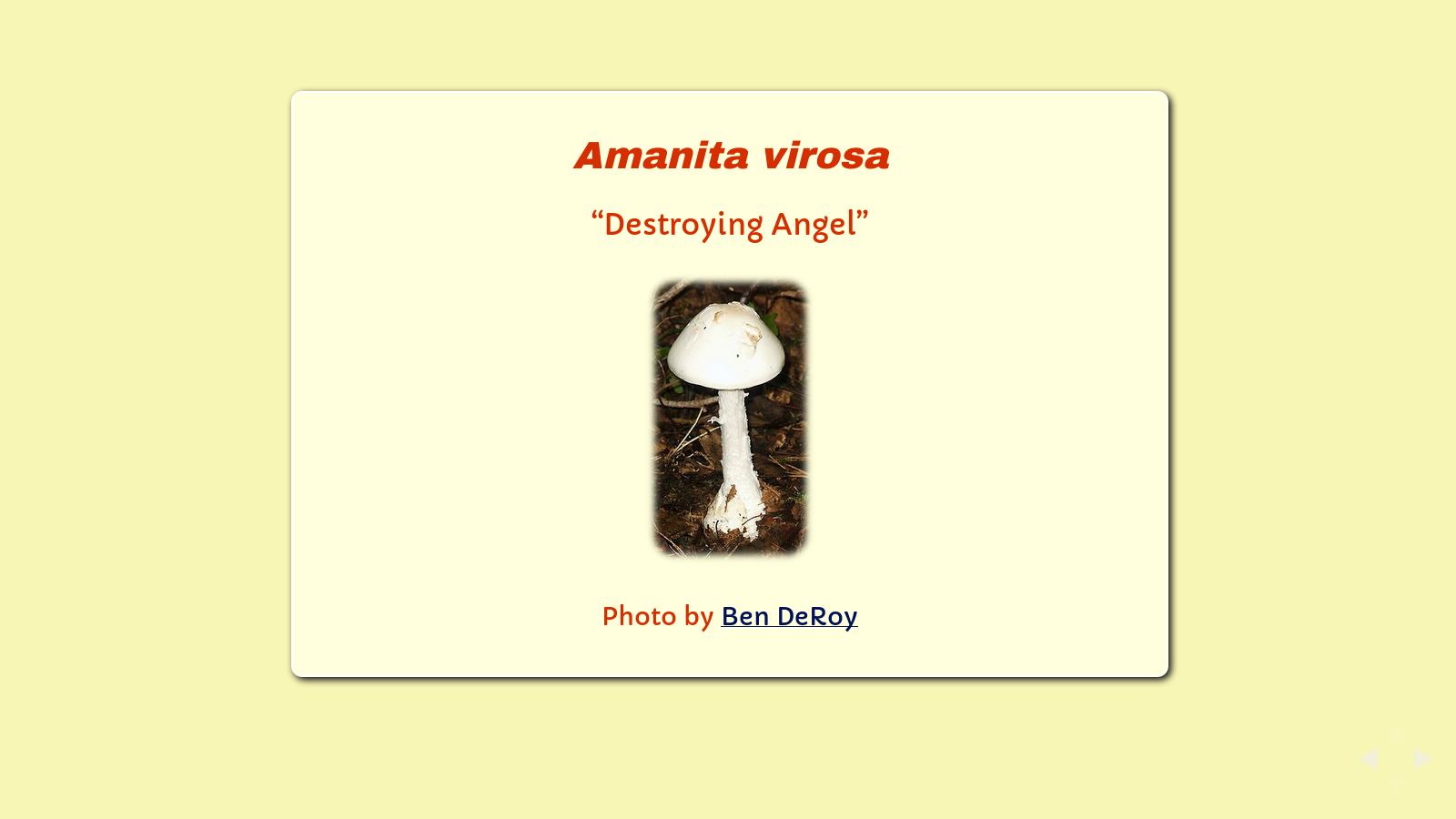

16 years ago my wife used a web authoring tool to build a botanical encyclopedia. That software is long gone. That data is locked up in a bunch of three and a half inch floppies. But the information is still relevant. I'm pretty sure that amanita virosa - the destroying angel mushroom - is still poisonous even if somebody stopped supporting the software.

The botanical encyclopedia she built is legacy data. If we do this right, we can instead build data legacies. Lets plan for that. Lets build rich models that demonstrate their own intrinsic value, that improve over time, and that provide services to the applications that call on them.

Thank you.